Much of Sigmund Freud’s work has been deemed pseudo-scientific, swept under the rug and into society’s (to use a Freudian term) subconscious. He is the father of psychoanalysis, and has left an indelible mark on the way we vocalize our emotions, both wanton and unclear (think libido, death drive, transference, Oedipus complex, etc.). Regardless of the validity of his theories, he has become a staple of popular culture, and has reshaped contemporary thought. As W.H. Auden so aptly poeticized: “to us he is no more a person / now but a whole climate of opinion / under whom we conduct our different lives.” And on December 12th, The Jewish Museum played host to the Austrian neurologist, as well as his thoughts on cinema, photography, and his own life. Alright, so technically “Freud” was depicted by Michael Roth, the president of Wesleyan, and interviewed by Jens Hoffman; but, beggars can’t be choosers. The interview forayed into the impossibility of repression, a mess of conflicting/unachievable desires that leaks out of the individual. Dreams were discussed as well, Freud likening them to puzzle pieces that are all mixed up, and which, when arranged, can depict unalienable truths about a human being. As the evening wore on, Hoffman asked Freud to analyze two photographs. One of them captured Jeff Koons’s Balloon Dog (Orange) sculpture, to which Freud noted the completely smooth exterior of the statue, the “surfaces of pleasure,” which bore no opposition to the subject’s wishes. He ended his examination by stating that the fantastical nature of Koons’s piece was “sweetly childlike.” I’m sure we can all conjecture as to what Freud made of the dog’s rigid tail.

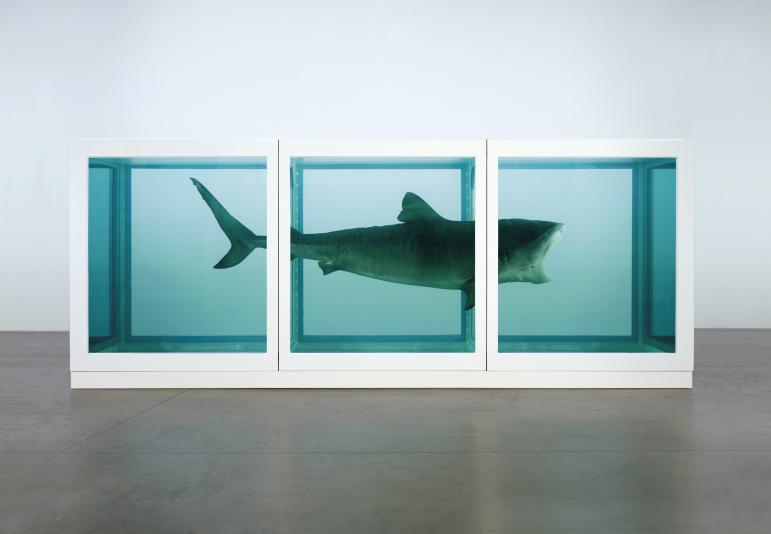

The second photograph Freud evaluated was of Damien Hirst’s The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, an artwork that displays a shark encapsulated in a glass case. Freud pointed out the obvious containment of death itself, allowing the subject to maintain a semblance of control over an entity so oftentimes unseen and unknown. While Freud was at times enlightening and transcendent, he seemed to be performing more shtick and appeared a lot more humorous than I would have expected out of the radical neurologist bordering on philosopher.

However, Freud’s comments made more of an impact when juxtaposed with The Jewish Museum’s showing of Love, War, and Exile, a Marc Chagall exhibit showcasing the French artist’s paintings from the 1930s and ‘40s. Many of the pieces portray Jesus and the Crucifixion. Yet, on some of the paintings’ peripheries, Freud’s ideas take shape: from the animalistic, hybridized humans representative of the id, to the inherent repressed pain and anger found in the intentionally messy brush strokes of red and blue, Chagall transmogrifies the fragile Jewish condition into unsettling images of humanity’s darker tendencies. The exhibition ends on February 2, 2014, and is a must-see for those who cherish a reflexive, visceral reaction to works of art.

Text by Paul Longo