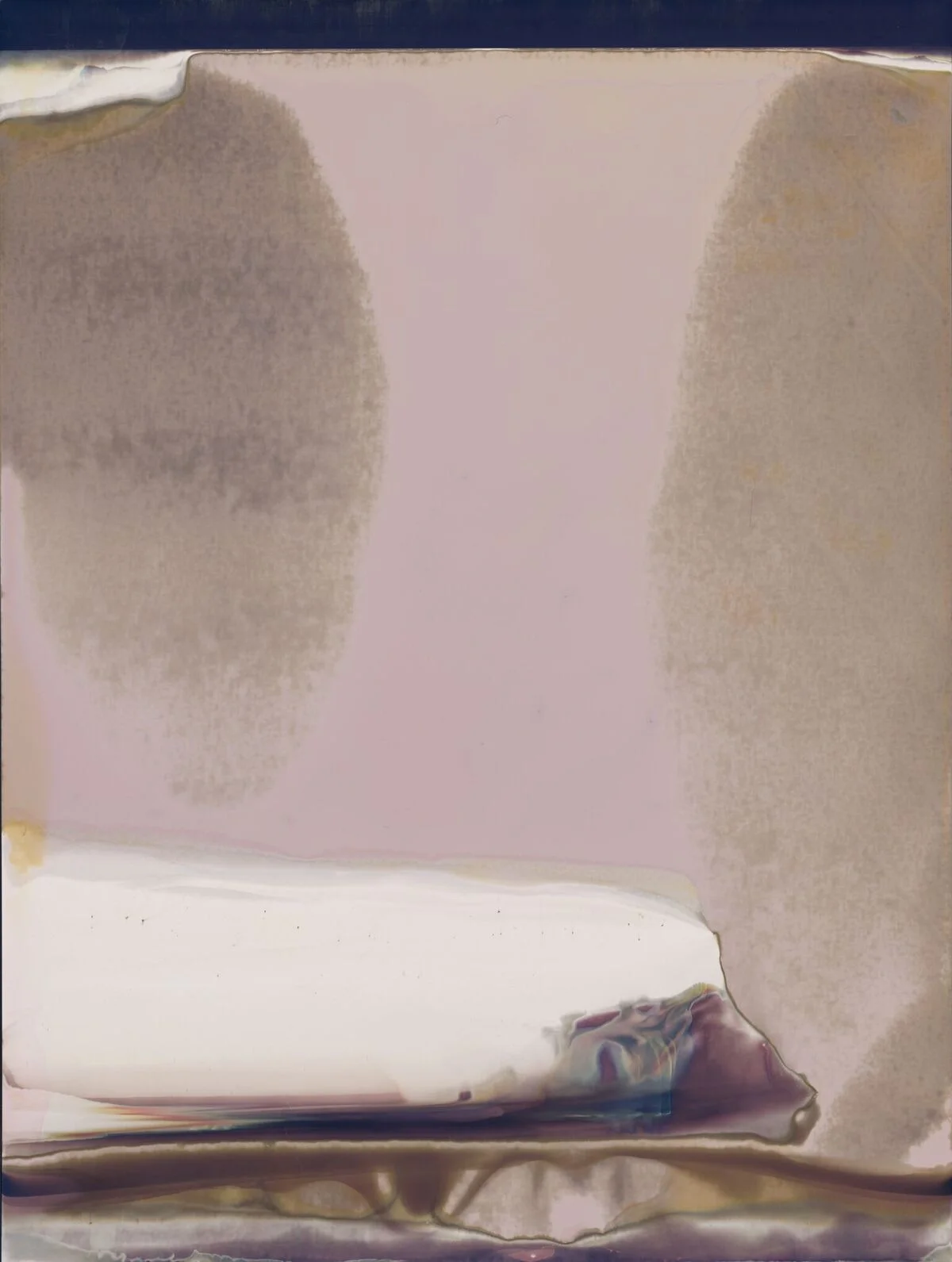

David Goldblatt's Johannesburg

George and Sarah Manyani 3153 Emdeni Extension, Soweto. August 1972

Photograph by David Goldblatt

Courtesy of Goodman Gallery and the Goldblatt Family Trust

The late photographer David Goldblatt (1930 – 2018) dedicated his life’s work to photographing his home of South Africa. Describing himself as a “self-appointed observer and critic of the society into which I was born,” Goldblatt documented the complex life experiences during the apartheid and explored the precarious post-apartheid democracy.

This expansive period saw Goldblatt produce more than 10 major photographic series – creating intimate portraits of his fellow South Africans and covering the country’s changing landscapes and evolving architectures. He lived in Johannesburg for 50 years, bearing witness to the city’s turbulent history. His renowned images form an incredible archive of its enduring trauma and resistance – a perspective highlighted in a recent exhibition at Goodman Gallery, London: David Goldblatt | Johannesburg 1948 – 2018.

© Goodman Gallery

The exhibition is Goldblatt’s first major solo exhibition in London since 1986 and follows his 2018 retrospectives at the Centre Pompidou in Paris and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney, Australia. Tracing Goldblatt’s 70-year career, the exhibition first introduces his socially engaged practice through a series of eight portraits. Taken between 1972 and 1973 at Hillbrow, a white working-class suburb in Johannesburg, the images depict both the white residents and the Black domestic workers of the area. The arrangement of these portraits contrasts the two groups, and the image captions, all of which Goldblatt wrote himself, reveal the deeply segregated community.

Baby with child-minders and dogs in the Alexandra Street Park, Hillbrow, 1972 (left), Rochelle and Samantha Adkins, Hillbrow, 1972 (right)

Photographs by David Goldblatt

Courtesy of Goodman Gallery and the Goldblatt Family Trust

The Black workers in Walking the ‘madam’s’ dog, 1972, and Baby with child-minders and dogs in Alexandra Street Park, 1972 sit uncomfortably next to the white subjects embracing their own families (Rochelle and Samantha Adkins, 1972, The housepainter and his family, 1973 ). The unwavering, challenging frown in the elderly Domestic worker on Abel Road, 1973 sharply contrasts the nonchalant, soft gazes of the young, white residents (Young woman on the stoep of a rooming house, 1973, An office worker from Tsmeb on holiday, in a rooming house on Abel Road, 1973, Schoolboy, 1972).

Cup final, Orlando Stadium, Soweto,1972

Photography by David Goldblatt

Courtesy of Goodman Gallery and the Goldblatt Family Trust

In his interview with Art21, Goldblatt described apartheid as “hard to grasp,” as the extraordinary contradictions were not always obvious. Yet his seminal 1972 photo essay of Soweto, a township in Johannesburg created by the government to house the Black population, clearly explores the city’s racial segregation and inequity. It is a series central to the exhibition, with multiple portraits presented alongside images of Soweto’s bleak landscape.

One of the most revealing photographs in this display is Young men with dompas, 1972, an intimate portrait of two friends, one of whom is holding a passport-like booklet that every Black South African was required to have under apartheid to be able to travel in and out of the white neighborhoods for work. It is an uncomfortable reality that is uncovered under the two men’s subtle smile and direct, defiant gazes.

Young men with dompas, 1972

Photograph by David Goldblatt

Courtesy of Goodman Gallery and the Goldblatt Family Trust

Goldblatt regularly used a large format camera, an instrument requiring a measured and formal approach to photograph his subjects. This allowed for deliberate, intimate encounters that heightened his acute observations. Goldblatt’s most expansive series, Structures, also highlighted this with a focus on the architectures and landscapes of Johannesburg and its surroundings. A feature in the exhibition, the project began in 1983 and continued on for 35 years, exploring the ways in which urban structures are, as Goldblatt describes, “declaration of values.”

In his images documenting various institutions, monuments, churches, and houses, Goldblatt investigated the fraught social, economic, and political histories of establishing South Africa. As questions of labor, access, and power are emphasized, this critical series extended Goldblatt’s socially engaged practice to reflect on a colonial legacy. And in the ongoing global reckoning of racial injustice, Goldblatt’s images continue to resonate.

‘Location in the sky': the servants' quarters of Essanby house. JeppeStreet, Johannesburg. 4 April 1984

Photograph by David Goldblatt

Courtesy of Goodman Gallery and the Goldblatt Family Trust

More of David Goldblatt’s work can be found through Goodman Gallery.