From the Issue: Vik Muniz

Vik Muniz, Museu Nacional, Museum of Ashes.

This interview appears in Musée Magazine Issue 23: Choices. You can buy a print edition here.

Steve Miller: Vik, your show really affected me. As a frequent visitor of Rio, it was distressing to read about the fire at the National Museum. Though, I was touched by your response to create new art from the ashes of the museum. How did this idea come to you?

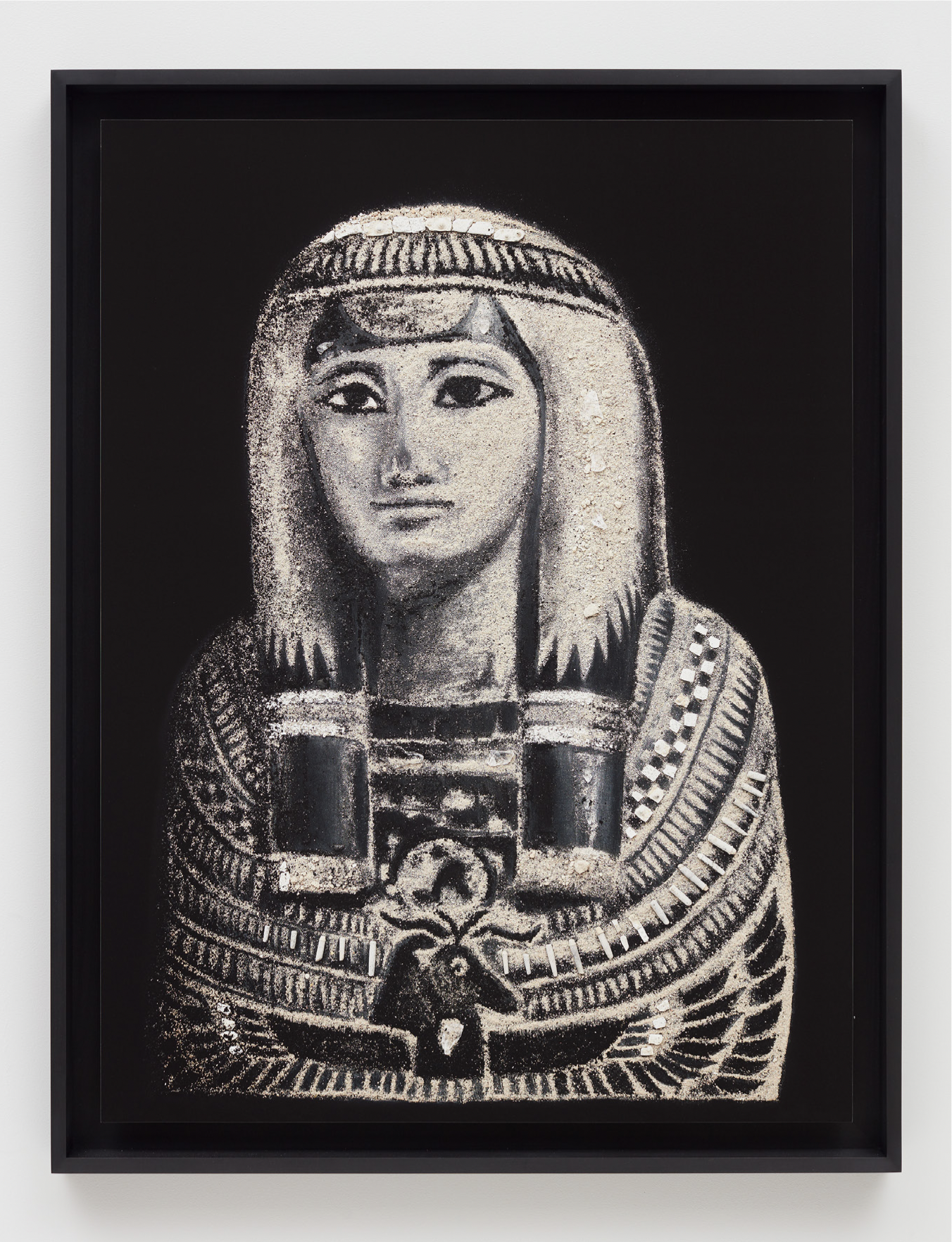

Vik Muniz: Thank you, we're going through a period of cultural unrest in Brazil right now. Just when you’re trying to work so hard to emphasize the role of a healthy cultural policy by the government and you’re really actively thinking about these things, then you get something like the fire...it's like, "God," it's so disheartening, you know? It’s really not what we needed. It’s like "what's next?" The National Library or the, National Museum of Art? I took it very, very badly. I take my children there. This was the only place in Rio that you had all the wonder. It was whimsical. You had mummies, you had Egyptian Sarcophagi, you had fossils, you had one of the largest entomology collections in the world!

The firefighters arrived in time and closed the areas affected to allow the desperate workers to salvage whatever they could, but when they found that there was no water in the building, they were forced to evacuate it entirely and try to extinguish it from the outside. The process took longer and caused a lot of water damage as well, hence so much destruction. It was a massive fire. All the floors collapsed. It was a 19th century structure that was home of the royal family since 1816. Pedro Segundo, the last emperor, amassed a vast collection of curiosities ranging from fossils, minerals and insects to Egyptian relics and indigenous artifacts. His fondness for cultural affairs led him to build the National Library, the Municipal Theater and the Fine Arts Museum. The Museu Nacional collection was the core of his scientific pursuits. He left the palace and was forced into exile, and the Republicans turned the property and its collection into a public venue. The museum incorporated a great number of collections and donations through the years and it had over 20 million items.

Although the news coverage interested me, it was the personal accounts of the tragedy that caught my attention. Everybody who spoke about it spoke in a very personal way as if it was their museum. It was more than a fire for people. It was the destruction of something quite whimsical and beautiful in their lives., I strangely shared those feelings, and that motivated me to work on the subject. I just wanted to bring a little bit of that back, that wonder.

Vik Muniz, Paleolithic skull (Luzia), 11,243-11,710 years, Minas Gerais, Brazil, Museum of Ashes.

Steve: If I understand correctly, you located from photographs, the objects, that would have been in the exact location where you collected the ashes, did I get that right?

Vik: Not exactly. I’ll tell you the whole story, okay?

Steve: Okay.

Vik: I was out of the country and called Fabio who worked for me., I said, "Listen, man, we've got to do something about it. Because, we simply have to show how we can help.” And then, in the days that followed, we came back to Brazil. Fabio tried to make contact with the people who worked at the museum, but everything was up in the air. They gave us all the contacts of the people who were working directly with the rescue team. We called them and they said, "You want to come and see it?" So we went. We made a few visits. What they are doing there is fascinating. They're doing a Meta Archeology. They have professional archeologists doing archeology in a place that was supposed to display archeology. So they're trying to find things that were found elsewhere. Egyptian things. Things from Pompeii! It's quite...it's amazing. They're trying to uncover history that had already...become history. It's something very postmodern, I think.

They had all this very well sorted out in Tupperware, or little boxes, catalogued with precise locations of the numeric grids they set out on the debris. They were looking for things, digging with little paint brushes. And sure thing, they said, "Yeah, we have everything from where we found it. Exactly." And I said, "So you have the dust from the case where you found Luzia, the earliest skull found on the American continent?" And they said, "Yeah, we have it for you.”

Vik Muniz Titanossauro, Museum of Ashes.

Steve: How did they know those were the ashes of the skull?

Vik: Because the skull was partially destroyed. They found the missing pieces. So, they gave us like a big Tupperware with this specific dust from the case of Luzia. I used it to draw the skull from older photographs using the dust from the skull. Pretty soon, I was drawing all the things I personally missed using the ashes from those precise objects. We have worked with the local universities on a number of technical matters, and a team from PUC came to the studio for an entirely unrelated matter, and saw what we were doing and told us that they were developing a similar project:, 3D printing with the ashes from CT scans they had had previously taken from a great number of pieces in the collection. We started working together, developing the objects for the exhibition. So far, we have printed Luzia, the Cat Mummy and a small Egyptian figurine, but we are working on making larger objects such a full-scale dinosaur for the show in Rio next March.

Steve: Right, are these the first sculptures that you've made?

Vik: No, no. I started as a sculptor early, early in the mid-eighties. And it was actually when I photographed the sculptures for documentation and for the press, that I figured out there was something between the sculpture and the photograph that was really cool. So, I started making sculptures just to be photographed, and that's how my work developed into this practice of making things and photographing them. I started with sculpture, so it's still my work. My work oscillates between material and pictorial. It’s all about this idea of a presence. It's between mind and matter. Always.

Vik Muniz, Seashell fossil, Paris Bay, 45 million years, Museum of Ashes.

Steve: So Vik, some of the images that you made you replicated from an archival photo, is that correct?

Vik: Yeah. Yeah, a lot of them are from pictures from the original museum catalog. They have a yellow book that was more of a scholar's tool, but with really, really great reproductions in it. So, more than half come from that.

Steve: With all of those options, how did you choose which objects to memorialize?

Vik: I did it based on the personal connection that I had with them. Obviously, the first one was Luzia because it was the most valuable, historical thing in the museum. And then the cat mummy was the museum mascot. When I took my kids there, that’s the first thing they wanted to see. They’d say, “Cat mummy!”

Steve: [Laughs]

Vik: It has a little bit of a face that's kind of cute.

Vik Muniz, Sarcophagus of Sha-amun-en-su, 750 B.C., Museum of Ashes.

Steve: You once said "When the mind wanders entirely ignorant of time, illusion becomes a means of confinement." I'm fascinated by what you mean by the illusion of confinement.

Vik: Yeah, well, we have developed tools as artists from the Neolithic period. Tools that were developed precisely to mediate between what's inside our heads and what's outside our bodies. Between mind and matter. Between consciousness and phenomenon. We've developed language. We've developed storytelling. We've developed means of visual description. Whenever somebody asked me about what art is, it took me a long time to describe it. But a few years ago, I came up with a very simple and synthetic way to describe it: Art is the evolution of the interface between mind and matter. It's very simple and it's about believing. And the only problem with this definition is that it serves for science and religion too.

Steve: Of course, illusion is one component of visual culture. And at the same time, fantasy projection is the abandonment of the necessary grounding needed to stay in the moment.

Vik: If you've come to think about it, every single species, as I'm talking to you, I'm seeing a hummingbird, flowers right outside my window. Every single thing that is alive, knows something. It has some specific kind of knowledge. It reacts to the environment. It has done things that makes it be alive today. We are not different, we evolved under the same concept, but we developed one quality that makes us different from any other living thing on earth. We believe. We have faith. We can think something is akin to stand for something else. We accept symbolic exchanges.

This changes everything. Every single thing that we've done up to very recently. All the images, the stories, all these tools, they were dependent on material support. If you asked me what is the ultimate tool that we've invented, I'm going to be forced to tell you it's the photo negative. Because the photo negative or the film negative, it has something that is tangible, you can hold it. It is a perfect tool between what's inside your head and what's outside in the world, because it has the characteristics that are material, physical, you can hold it in your hand. But also, when you look through it, it stirs emotions in you, memories.

Vik Muniz, Cratera em calice, Italiota, Museum of Ashes.

However, the image has become autonomous in the digital era, it no longer needs a physical support to exist. You see, we've developed these tools to deal with situations that haven't happened, or replicate things that happened in the past. It's all about model making. It's all about creating things that have a relationship to things that exist, but all you have to do is imagine them. What was make believe model making has become a surrogate for our physical environment. The image no longer needs a physical support. The story no longer needs a paper to be written on. You don't hold books anymore. You can listen to them or you can just see them in your phone. That is the new information. The world doesn't come through to you by physical means, and that changes our relationship to things, facts and ultimately to history.

Fifteen years ago, I was teaching my students at Bard about Photoshop. I was totally convinced that something as simple as Photoshop would have an enormous amount of impact in the way we understand reality. Physical reality offers limits for transformation, while image manipulation can transform and distort reality indefinitely Our main problem as we struggle to adapt to these fast-changing technologies is that we have lost our means of connecting the psychic to the material, and that has caused a seemingly unsurmountable chasm between what we feel and what we think. Never in our history did we needed so much to re-evaluate our relationship to our material culture. When you go to museums, you see evidence, physical evidence of things that happened. And once this thing goes up in the air in flames, it becomes memory. It becomes just media. It becomes pictures. It becomes part of everything else that you have today, everything that is existing, but only inside our heads.

Steve: There is something basic and materially real and touching, actually, about your documenting your experience of the fire. Fire is also on the mind of the entire world as we collectively watch the burning of the Amazon, the lungs of our planet. Was this parallel to your thoughts while making this work?

Vik: So many major fires have happened in my life...I remember the Twin Towers, now yes there's the big one in the Amazon. I was just there, actually. I was there during the fires. I went in a small airplane for two hours. How we saw the smoke was crazy. I've never seen that and I've been there many times. Fire consumes in a way that you can never quite reconstruct. Fire has that kind of power, that can sort of erase history. But I find that to be a very contemporary theme. I know they’re happening in California too. And people are still thinking that there's nothing wrong with the planet…

![6 Questions with: Vik Muniz [VIDEO]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5702ab9d746fb9634796c9f9/1601411128823-TJNNDC3J1VAQNBWOYOM7/YouTube-6Q-VikMuniz.JPG)