From Our Archives: Alfredo Jaar

From Musée Magazine Issue 16: Chaos. Here’s an interview from 2014 with Alfredo Jaar. Last week, Alfredo won the 2020 edition of the prestigious Hasselblad Award for Photography for his beautiful and politically driven work. He discusses his perspective on difficult issues and his art below.

MUSÉE: Our issue is about chaos. How does chaos influence your life and your work?

ALFREDO JAAR: If we look at the state of the world, chaos, unfortunately, is our present condition.

I am reminded of a famous Chinese proverb: “Better to be a dog in a peaceful time, than to be a human in a chaotic period.” Well, as a human in this chaotic period, and as an artist for whom context is everything, chaos is then my context. I have no choice.

MUSÉE: It seems your work is largely about human impact, how our actions influence the world around us and how we are not likely to stick around to watch the world burn after we toss the match. To me, you hold up the mirror. What impact would you like your work to have?

ALFREDO: I hope to offer a little hope in a time of despair. But it is difficult. I remain a Gramscian: I am a pessimist with my intellect, but an optimist with my will.

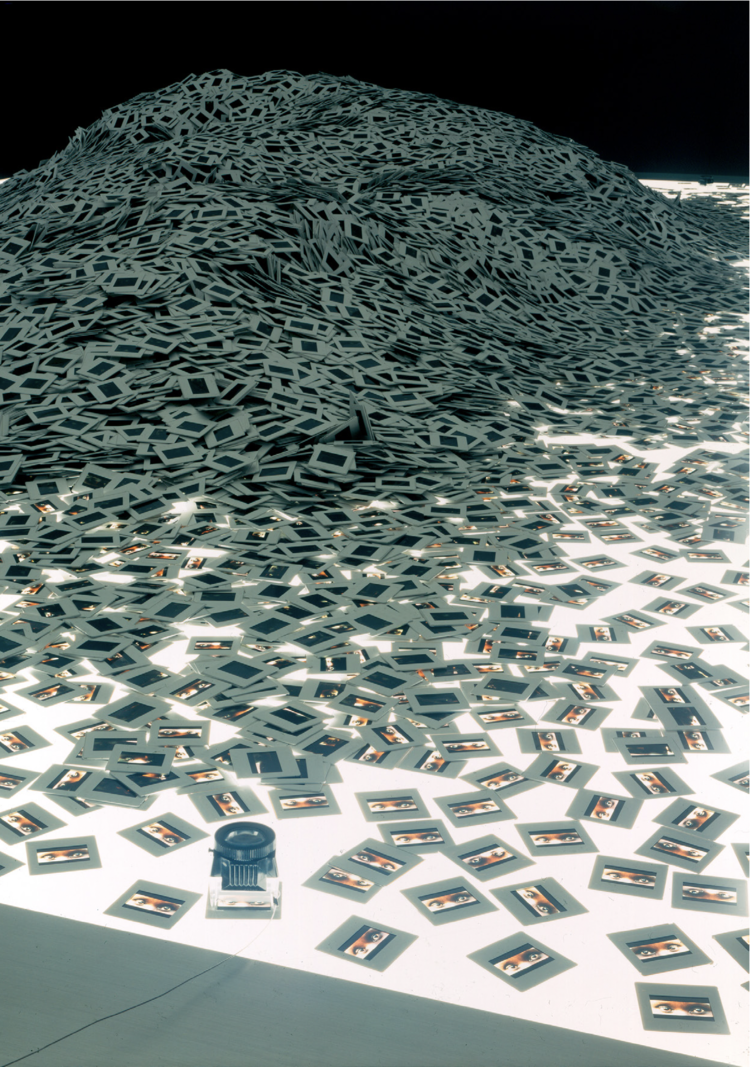

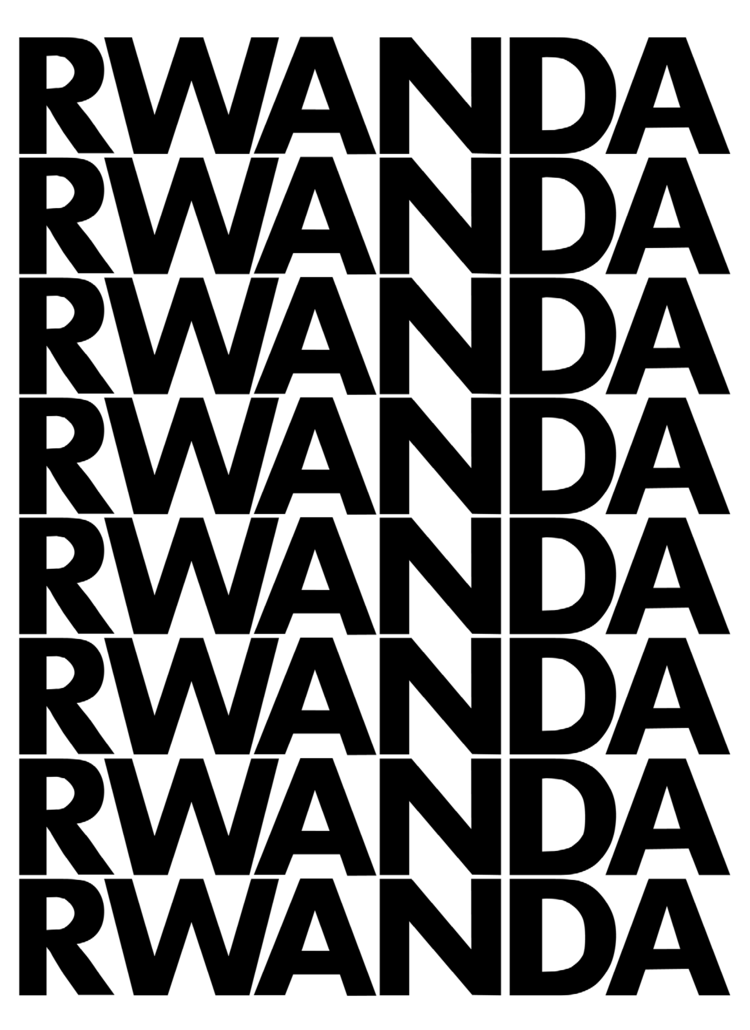

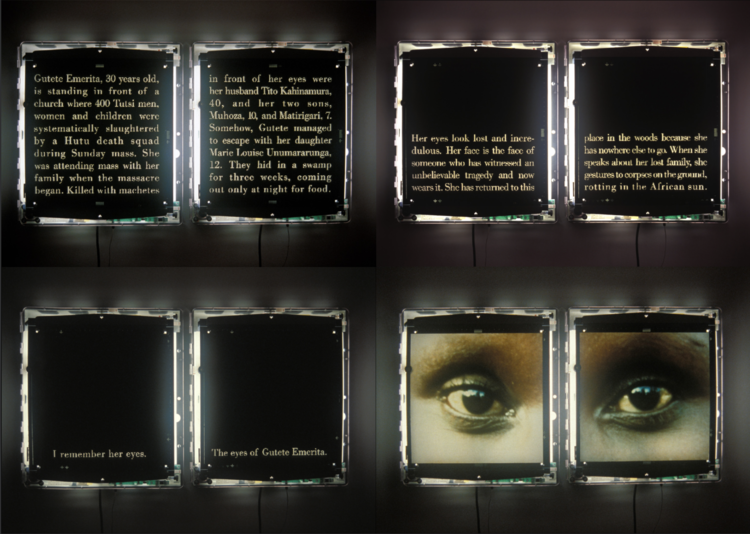

MUSÉE: I would like to begin with your Rwanda project (1994-2000). I specifically want to touch on a line that struck me in Ben Okri’s essay that accompanies the work: “The world was now at the perfection of chaos.” What comes to mind when you hear this?

ALFREDO: That is one my favorite lines from Okri’s essay. It is brilliantly devastating: chaos has indeed reached heights of perfection thanks to the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council. As you know, these five countries are also amongst the biggest arms dealers on the planet. They are merchants of war, and at the same time, the most cynical brokers of peace. The current chaos is their masterpiece.

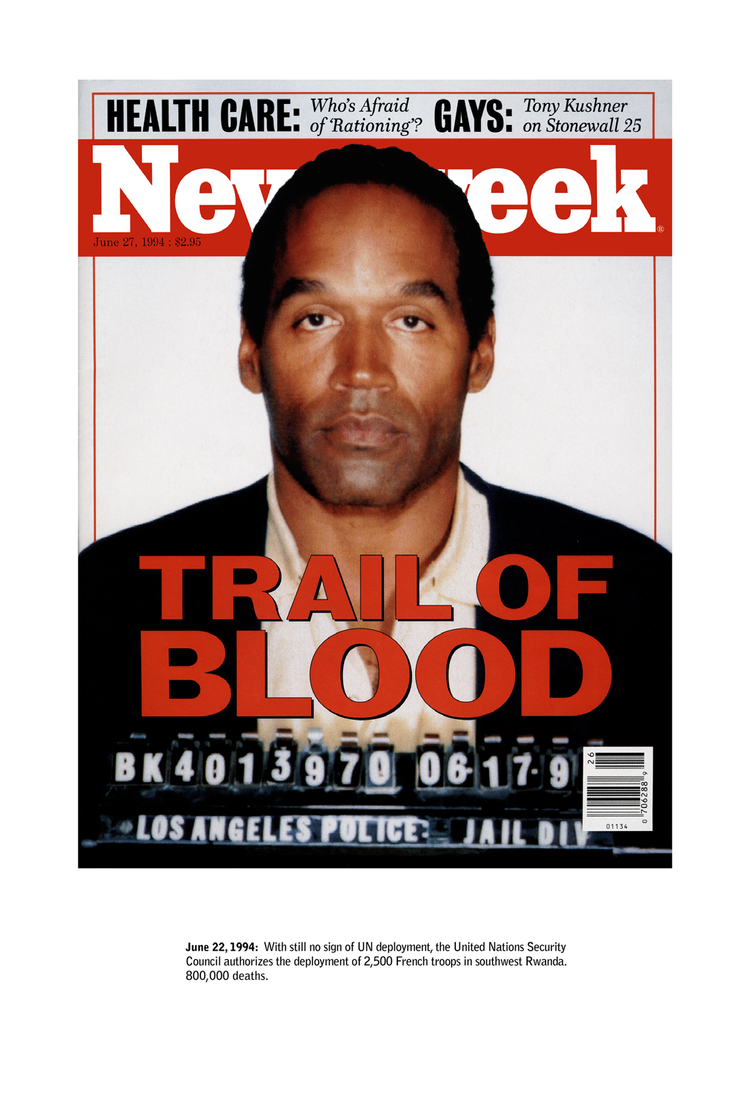

MUSÉE: You have been called a moralist. In your (Untitled) Newsweek (1994) project you explore the media’s disregard, or immunity, to the genocide in Rwanda. In your opinion, what other events have they fallen short on?

ALFREDO: Most of the media today is owned by enormous for-profit multinational corporations and they are supported by advertising. Independent, critical journal- ism has practically disappeared. We live in a deeply un- informed democracy: the genocide in Rwanda is just one of thousands of stories ignored by corporate interests. The show must go on, they say.

MUSÉE: I saw your project “Lament of the Images” at MoMA and it really struck me. Bill Gates and the “safe- keeping” of 17 million pictures, as well as the US Defense Department’s retrieval of all the satellite images of Afghanistan during the 2001 air strikes—what do you think these actions say about the powerful nature of the image?

ALFREDO: Images are important, because images are not innocent. Each image and every image that we produce contains a conception of the world. Most of the images we are confronted with in our daily lives have been created by experts in communications at the service of a system of consumption: they exist to sell us products, and ideas. As a recent work of mine suggested, “we do not take photographs, we make them.” And those making them today are producing invitations to consume, consume, consume. And in that sea of consumption, it is very difficult for an image of pain to survive: it is drowned.

MUSÉE: You have said that the hardest thing for your creative process is arriving at what you’d like to say about a subject. How do you get there? Can you provide an example?

ALFREDO: Context is everything. I need to understand the context before creating a work. That is why my modus operandi has always been the same: before acting in the world, I need to understand the world. That understanding is the result of a long period of research that can last years. Only when I reach what I believe is a critical amount of knowledge, when I feel that I have acquired a responsible amount of information about the context, only then I dare to start articulating possible ideas.

MUSÉE: I know you’ve trained as an architect; what sparked the use of photography as a medium in addition to your installations? How and when do you decide which medium you are going to use?

ALFREDO: My work is not medium-specific but idea- specific. The final project is an idea that requires a medium. And that medium is at the service of the idea.

MUSÉE: I’ve seen Susan Sontag referenced often in accordance with your work. I saw a quote of hers that particularly resonated with me: “Literature can train, and exercise, our ability to weep for those who are not us.” You use a lot of text, primarily poetry in your work. What is the significance of your use of literature in your work?

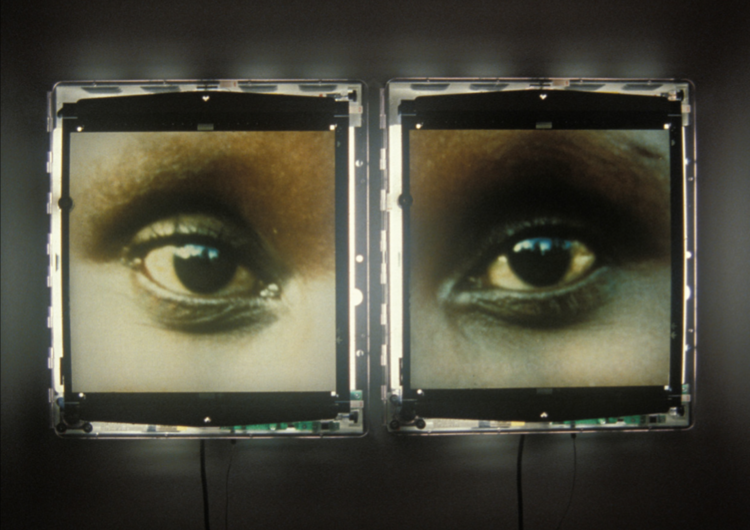

ALFREDO: My work changed radically after my experience in Rwanda where I witnessed a genocide that left one million people dead in the face of the barbaric and criminal indifference of the so-called world community. After that experience, my relationship to photography changed. I started using more text and less images. I distrusted photography’s capacity to affect change in the wake of the genocide. But words failed me too. As Adrienne Rich wrote, “tonight no poetry will serve”. How do you make art out of information that most people would rather ignore? I have no answers to this question.

MUSÉE: Moravia has said that there are only three or four great poets born every century. Who do you think falls into that category today?

ALFREDO: The great poets of this century are yet to be born. But from the last century, in my reading list you will always find Giuseppe Ungaretti, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Anna Akhmatova, Adrienne Rich and Ben Okri, as well as Rubén Darío, César Vallejo, Raúl Zurita, Nicanor Parra and Vicente Huidobro. I find solace in their words every day.

MUSÉE: You recently did a project in Switzerland at Art Basel where you distributed boxes containing the im- age of the beach where Alan Kurdi, a boy who drowned at sea trying to escape Syria, washed ashore. What about the Syrian crisis compelled you to create this project?

ALFREDO: I was invited by Art Basel to create a public intervention. I had been following the so-called immigration crisis for a long time and I felt compelled to react to the desperate situation of the millions of Syrian refugees trying to reach Europe. I created “The Gift” to try to raise funds for MOAS (Migrant Offshore Aid Station), a young NGO that is dedicated to save people at sea. With the exception of Germany, Europe’s reaction to this crisis has been despicable and I needed to express my indignation through a project. In the end, as it always happens, I managed to channel my rage in a constructive and creative way. With “The Gift,” I attempted to engage a very wealthy audience into thinking about this crisis and give visibility to a fantastic organization saving thousands of lives at sea. In fact, MOAS saved more than a thousand people during Art Basel.

MUSÉE: It feels as though the Syrian refugee crisis is the epitome of chaos. Do you have any further projects coming up about it?

ALFREDO: I am not a studio artist, but a project artist. All my work is born as a reaction to the reality that surrounds me. And the Syrian crisis is a world crisis that we must address. Chinua Achebe wrote that “Art is man’s constant effort to change the order of reality that was given to him”. That is what I try to do. I still do not know how to change this order of reality, but I am trying hard. It is also clear to me that my work is always born out of chaos.