#WHM Sarah Charlesworth

We’ll be tapping our incredible archives in support of Women’s History Month and International Women’s Day and posting interviews from our Women issue throughout the month of March.

Sarah Charlesworth she stands alone

Sarah Charlesworth.

By John Hutt

Sarah Charlesworth never really liked being called a photographer; she was a conceptual artist who worked with photographic images. Charlesworth’s shows are often accompanied by immense blocks of wall text that meticulously explain each picture in detail, giving background and theory. While at other times Charlesworth simply presents an image and lets the viewer add their own cultural and emotional significance. As the artist rejects the label of photographer, it’s important for the viewer to examine her work as a conceptual or theoretical exercise. That’s not to diminish her works aesthetics, in fact it is as important to label the artist ‘photographer’ and enjoy her color fields and objects. Both reveal the artist. In one of her early works, a highly theoretical and dense publication entitled The Fox which she published with Joseph Kosuth, Charlesworth writes essays that should be held up along side her images as an important part of her catalog. Her work as a theorist and critic is too often forgotten. This may be because The Fox is pretty impenetrable to the uninitiated, or it may be because it came out years before Charlesworth was known, a deep cut. She writes

“ If we recognize the institutional structure of a complex society to be (culturally) all-embracive, then we may begin to see that in attempting to re-define, alter or redirect the social definition or function of art – the manner and channels through which we can effectively work – we are encountering a firmly entrenched and highly developed institutional order: not just when confronting the obvious bureaucratic structure of the New York art world, but encountering the force of that order on every level, from such specific factors as the persistence of socially convenient(marketable) formal models of art (i.e. painting and sculpture) to more abstract socially convenient (non-controversial) theoretical models (formalism, art for art’s sake), to the most blatant sociological fact that cultural power is clearly allied with economic power, and that to a large extent the internalizations of the dictates of the productive system regarding patterns of legitimation on consumption are the very means by which individuals surrender their critical faculties to that system”.

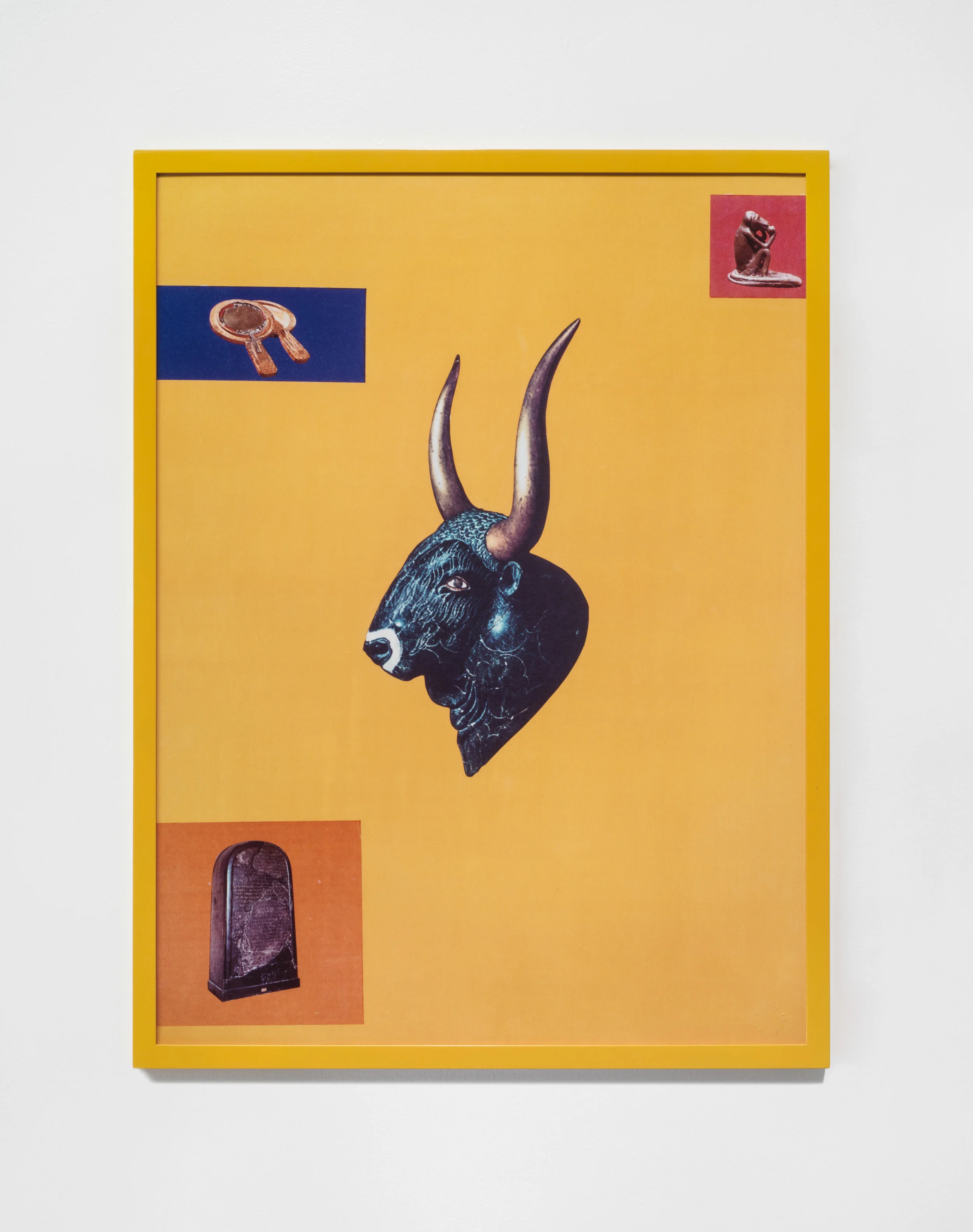

Bull, 1986 © Sarah Charlesworth

Goat, 1985 © Sarah Charlesworth

Perhaps this is why Charlesworth, despite being a member of the influential and successful ‘Pictures Generation’ with friends Cindy Sherman and Laurie Simmons, never met with as much success as her peers. Her Marxist and theoretical roots resulting in a view and statement of the art market which is perhaps more true now than it was in 1975. Charlesworth refused to surrender her critical faculties to a system.

Her series found images of people falling were where she met her first success. The works in her “Stills” series was variously viewed as harrowing, morbid, and beautiful. The large scale pictures of people falling, presumably to their deaths, are blown up so far as to be out of focus blurs. The viewer can step into the pictures, seen up close a mass of black and greys, seen far away a dying human. “Stills” shows moments between life and death, the subject is immortalized by the picture, and while the subject is also dead, their picture hangs on a wall in Chicago. “Institutions tend to claim authority over the individuals and their activity in society regardless of whatever subjective meaning they may attach to their situation and endeavor.” What subjective meaning have the falling people attached to their endeavor, if one can call it that, and what subjective meaning has Charlesworth attached, if any, and what meaning did the New Museum attach when the images were displayed earlier this year?

Installation view, courtesy New Museum

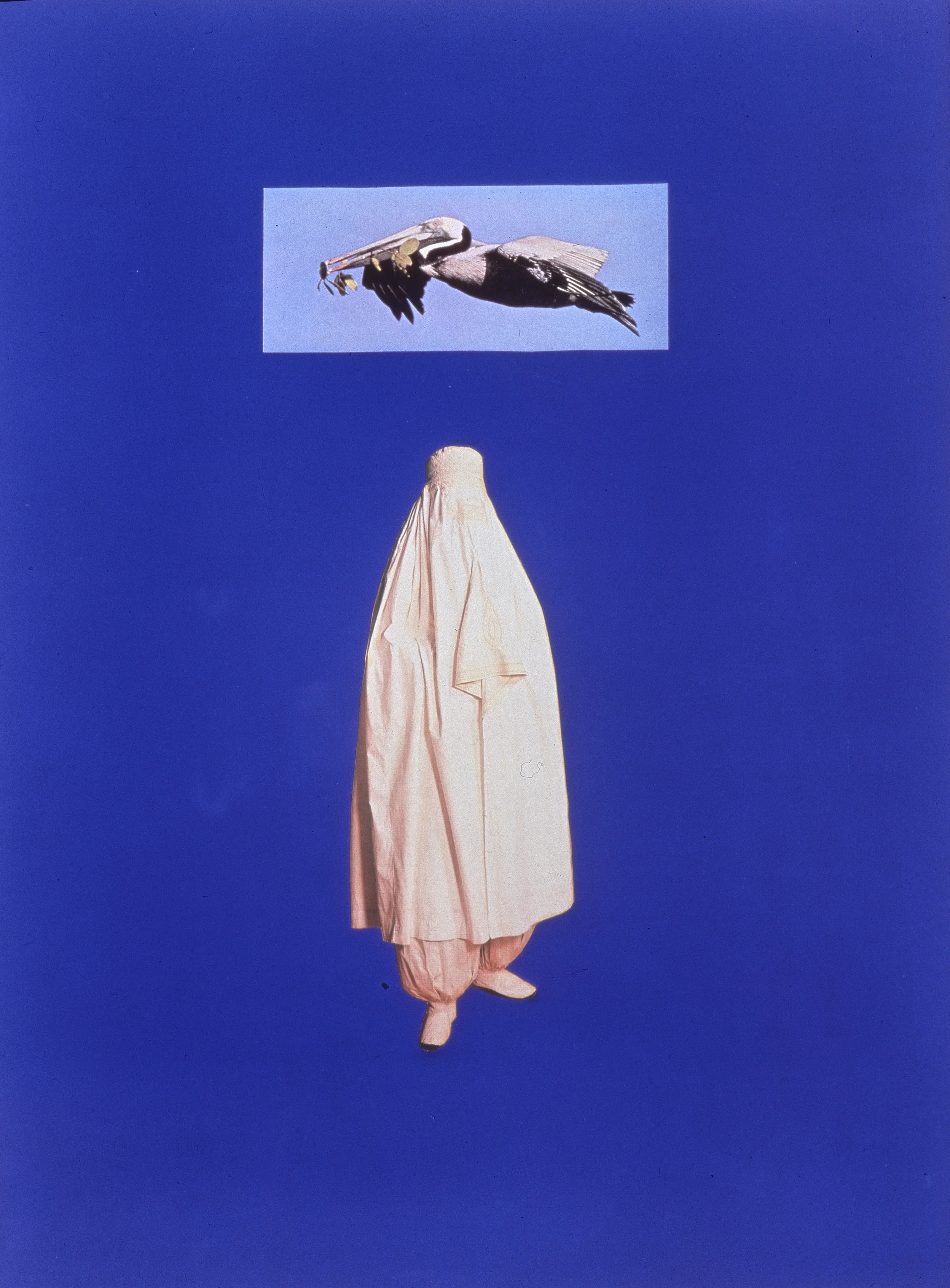

In discussing Charlesworth it is fitting to include quotes from her. Any of Charlesworth’s works can be endlessly dissected, and are, publically or otherwise, by the artist. There will never be a work by Charlesworth that has not had a paper’s worth of critical theory put into it. Whereas other artists such as Taryn Simon, who are influenced by Charlesworth’s work, use their process as part of the overall concept, Charlesworth does not. In her mind the image is the final arbiter of the concept, as lofty as that concept may be, the image is a direct result. This can lead to lengthy after the fact explanations of what the concept is. Nowhere is this more present than in her “Object’s of Desire” series. Using found pictures of objects Charlesworth imbued them with magical energy and juxtaposed them with another image in her own brand of dialectical mysticism. Charlesworth loves objects. She liked the tangibility of them, she, according to Laurie Simmons in conversation with the New York Times: “…was the kind of person who would hold something in her hands and tell you about the properties and what she felt. Something made of pewter was really alive to her. A cup made of copper could take over her whole consciousness.” This shows in her dialectic objects. “The art work as a symbolic token of the struggle of the individual artist and the spiritual and social dilemmas which that individual struggle in turn reflects, becomes in a sense a sanctified cultural relic, presumably embodying in itself some elusive imaginative spirit. One wonders, of course, why it is the tokens of struggle toward meaning and not the struggle itself to which we respond.” A statue of the Buddha sits serenely, a circle in a ceiling revealing the sky is next to it. Is it so obvious as to simply state that there are two kinds of enlightenment? With Charlesworth it never is, but that does not stop the original response being true. It is easy to get lost in the theory behind her work, it’s equally easy to look at her work as aesthetic objects, things of beauty and resonant emotion, not everyone at galleries reads the wall text, not everyone will read Charlesworth’s essays, but they will remain there for those who want to go deeper, and the experience is rewarding. Or one can just look at her work and react, she gives that freedom of choice.

“You cannot, on the one hand, claim that all knowledge is culturally determined, socially derived, and then in turn claim the objective validity of your own theory. In this sense the dialectic becomes immanently useful as an ideal working model but in practice something of an impossibility. So we proceed amidst contradiction.”

Buddha of Immeasurable Light, 1987

Birdwoman, 1986 © Sarah Charlesworth