#WHM Grete Stern

We’ll be tapping our incredible archives in support of Women’s History Month and International Women’s Day and posting interviews from our Women issue throughout the month of March.

Grete Stern the dreamcatcher

Grete Stern Autorretrato (Self Portrait) 1943. All images © Estate of Horacio Coppola

Written by Parinatha Sampath

Pablo Neruda once said, “You can cut all the flowers, but you cannot keep spring from coming.” This quote makes me wonder if he had his close friend in mind, Grete Stern. Given the political scenario in Germany and the gender-social constructs of the early 1900s, it was nearly impossible for a woman to dream of a full-fledged career. But Stern chose to defy gender stereotypes, explore the world through her lens, and create a unique and innovative mode of expression.

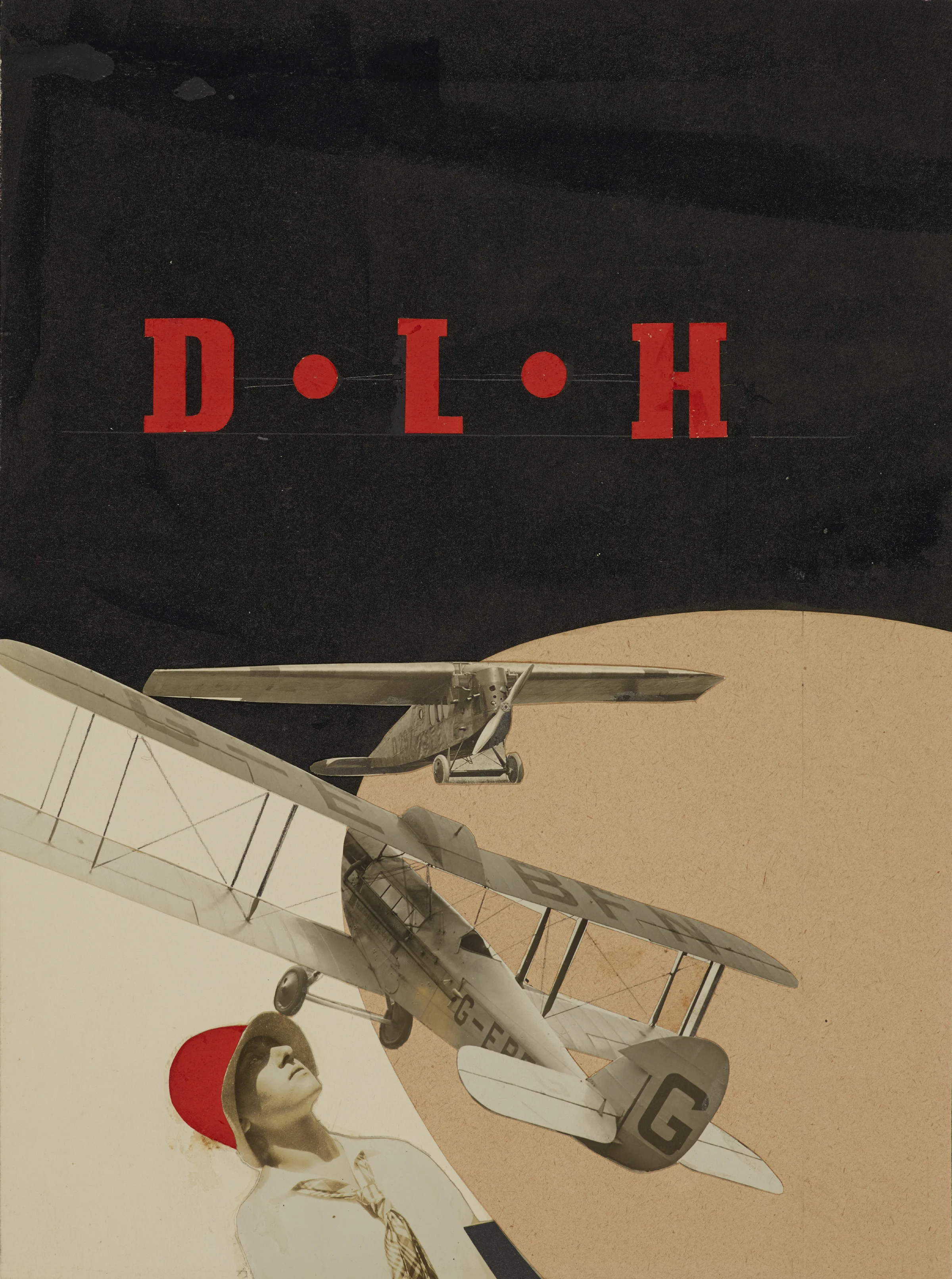

A few years after her education in graphic arts (compounded by limited opportunities in war-torn Germany), she moved to England and established a studio along with friend and fellow-student, Ellen Auerbach. Their work, later critically acclaimed for its unconventional depictions of women, blended art and advertising with avant-garde typography and photographs of products resembling contemporary still lifes. Though Stern began to enjoy a successful career, her thirst for education didn’t fade. She returned to Berlin, studying at the Bauhaus. In addition to learning new photography techniques from Walter Peterhans, she met the Argentine photographer Horacio Coppola, whom she married in 1935.

© Grete Stern

The couple traveled to Argentina, settling in Buenos Aries, and co-presented what is considered the first modern photography exhibition in the country. A few months later, a pregnant Stern decided to leave her husband and return to England. Although reasons for their split are unknown, rumors suggested Coppola showcased Stern’s work as his own without giving her credit.

Stern returned to Coppola a few months after the incident and continued portrait work. She took portraits of family and friends, including frequent visitors Pablo Neruda, Bertolt Brecht, and Jorge Luis Borges. The couple’s home was known as a welcoming place for European exiles—Jews, intellectuals, and artists alike escaping persecution. Most of these exiles even modeled for Stern. Stern approached each portrait with subjects shot in plain clothes, in front of simple backdrops, from a birdseye view, and focused on their faces. Her female portraiture highlighted femininity and exuded an independent spirit—a rare perspective for this period.

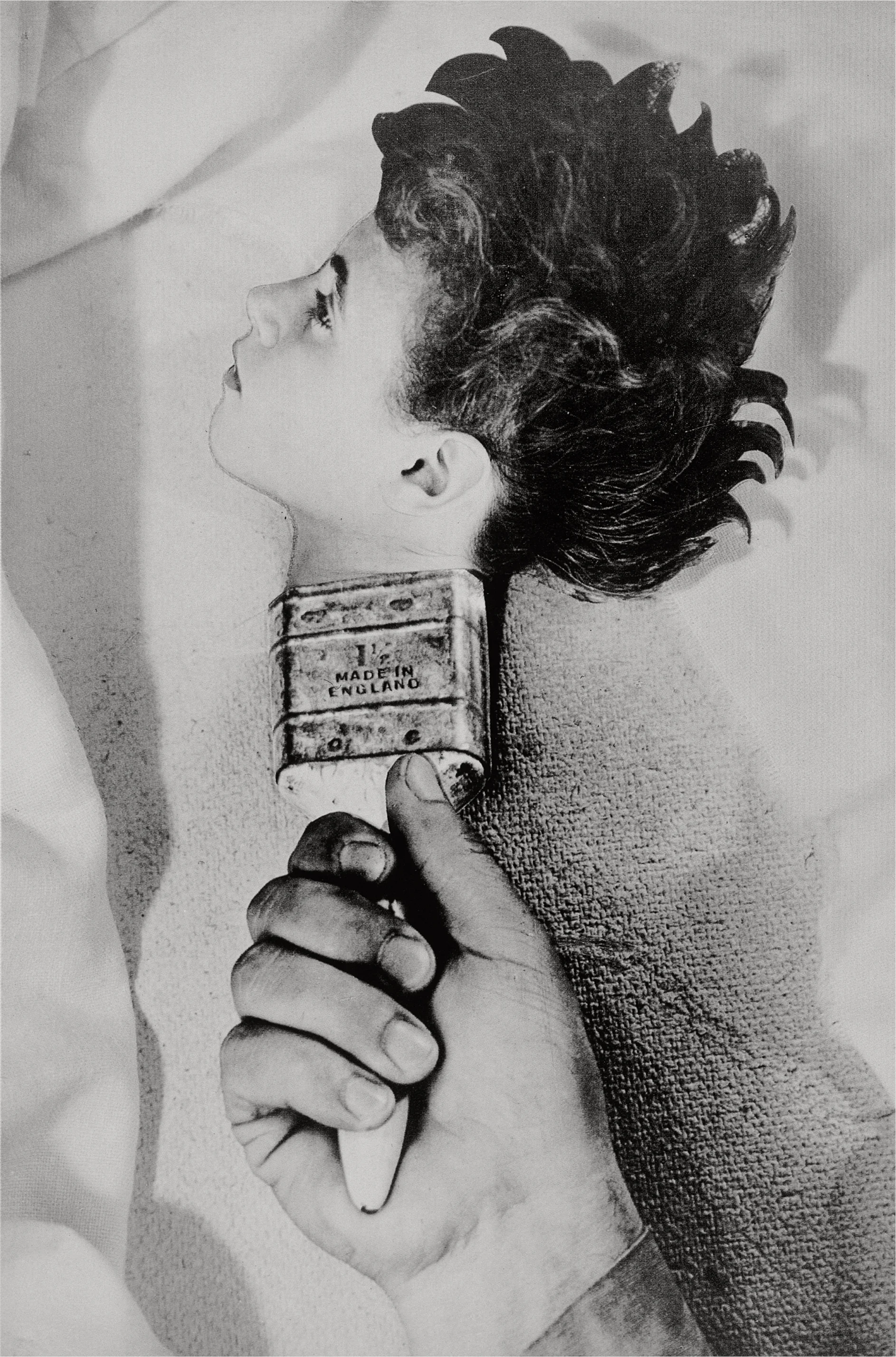

Grete Stern. Sueño No. 31: Made in England (Dream No. 31: Made in England) 1950

While Stern’s photographs of Argentina’s indigineous people, cityscapes and nature brought praise and greater opportunity, her most captivating, noteworthy project was a photomontage series, Sueños, with the women’s magazine, Idilio from 1948-1950.

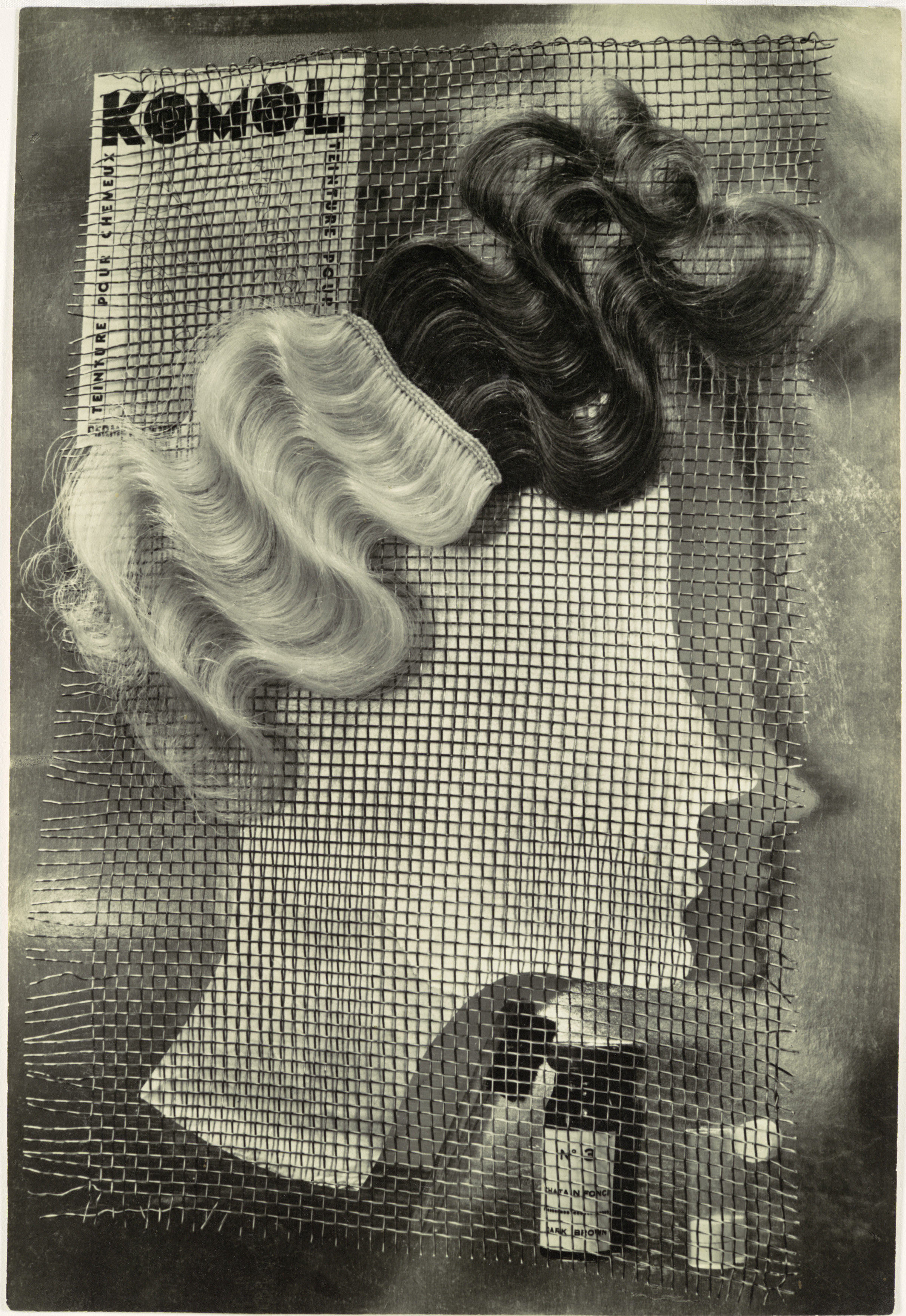

Over 150 of Stern’s surrealist images accompanied the column El Psicoanálisis le Ayudará (Psychonalysis Will Help) at a time when pop culture was obsessed with Fruedian concepts. With the Sueños series, Stern visualized dreams submitted to the magazine by its female readership, reinterpreting themes of female objectification and domination within patriarchical constructs. Stand-in motifs, or male figures themselves, highlighted the prevailing attitude of the Peronista Period regarding appropriate female roles and the manner in which society controlled and perpetuated these values. Characteristic of these photomontages, women occupied domestic spheres, were maternal figures, or resigned as objects of a male gaze (with eyes glazed over in daydream-like states, alluding to a lack of focus and disassociation from reality).

© Grete Stern

In one work, a modestly-dressed woman is situated at the base of a lamp. The woman is miniature, to scale with the lamp. The woman kneels, arching her hands back to support the lampshade, and stares off passively as a suited male figure, from the shadowed background, reaches with his large fingers for her legs in an effort to switch off the light. The discrepency in size between male and female subjects suggests the inequity of power between the two sexes. The female subject is stationary, part of an inanimate object, reserved to the whims of an active, controlling male figure. Contrast is further exemplified playing with light and shadow amongst the genders—light hinting at female purity and the shadow, darker, immoral thoughts of the male. Furthermore, arranging the female figure in the light, substituting her small frame as an element of a standard household object, perpertates fixed gender roles that a woman’s place is in the home—she shines in the domiciliary, she is a critical mechanism, literally supporting the inner-workings of the household.

Another of Stern’s Sueños photomontages depicts a trifling woman traipsing through a library bookshelf, picking flowers blooming from T. E. Lawrence’s (aka Lawrence of Arabia), Los Siete Pilares de la Sabiduría (Seven Pillars of Wisdom). The title of Lawrence’s autobiographical novel serves as a strong symbol with its biblical reference to the Book of Proverbs: “Wisdom hath builded her house, she hath hewn out her seven pillars.” Again, this juxtaposition maintains traditional gender roles in which the youthful woman is relegated to the domestic sphere—specifically gathering flowers from a volume providing her with the wisdom necessary to build and oversee a future, orderly home.

Sueño No. 1: Artîculos eléctricos para al hogar (Dream No. 1 Electrical Appliances for the Home) 1949

Moreover, Stern had a tendency to represent women as fragments of their whole self. A memorable photomontage affixes the profile of a woman’s crown, her mane coarse and disheveled, replacing the hairs of a paintbrush. A male hand controls and navigates the brushstrokes of this hybrid female/paintbrush as it travels over white bed linens. In keeping with psychoanalytic thinking, one can assume the female figure feels disengaged from her sexual self. Her body is not her own, but merely an instrument of manipulation and enjoyment for the male.

Though Stern had always championed the cause of women, her proto-feminist self was unleashed with Sueños. She infused sympathy, dark humor and playful irony in her photomontages as she visualized the subconscious narratives of these women. Stern’s decision to portray women in fragmented, disjointed manners, or reduced in part or whole, speaks to a dominanting sense of disconnect from the self and overarching state of female powerlessness among middle-class, Idilio subscribers.

Sueño No. 27: No destiñe con el agua (Dream No. 27: Does Not Fade with Water) 1951

After Idilio, Stern went on to social work with native Argentinans. She captured the poverty-stricken life, craft-making skills, and the daily routines of aboriginals. So moved by the under-privileged, she hoped her work would prompt some change in their lives; however, sadly it did not.

While Stern constantly fought against stereotypes and gender discrimination, her greatest challenge was coping with the loss of her son Andres, who committed suicide in 1965. Though she personally suffered from terrible bouts of depression, she did not let it affect her passion for photography. Instead, she began to teach the subject in various schools upon invitation.

Grete Stern’s life was imbued with uncertainty and transience. Her photography was diverse in terms of the locales, styles, and subjects; however, a subtle aspect coursing through Stern’s work is her undying love and passion for the art of photography. Through all obstacles—immigrating from Germany, navigating a male-dominated field, divorce, and losing a child—all of this simply bolsters Neruda’s quote: “You can cut all the flowers, but you cannot keep spring from coming.”

© Grete Stern

Photomontage for Madî, Ramos Mejîa, Argentina. 1946-47