Image above: Lyle Ashton Harris by Rob Kulisek.

Lyle Ashton Harris’ new show at the David Castillo Gallery in Miami is comprised of a series of Ektachrome photographs the artist took in the 80’s and 90’s. Ektachrome, a Kodak film brand that has been discontinued, was invented as an easier and faster film development alternative to their other brand, Kodachrome. As a less laborious development process, Ektachrome was useful for capturing candid moments in an era just preceding digital. The quality of Ektachrome images is distinct: colors are bold and vibrant, yet there is a softness to the light that lends to the images the warm haze of memory, a duality of directness and distance. This duality is apparent in the content of Harris’ images: many of his subjects stare directly at the camera, while others ignore it or are unaware of it; some of the images are boldly matter-of-fact (in one self-portrait, the artist reclines post-coitus, his penis still emitting ejaculat) while in others his treatment is quieter, as in the “Sleeping Boy” photographs.

©Lyle Ashton Harris, Sleeping Boy Two, Bronx, New York, Circa Late 1980s. Courtesy of the artist and David Castillo Gallery, Florida.

©Lyle Ashton Harris, Sleeping Boy Two, Bronx, New York, Circa Late 1980s. Courtesy of the artist and David Castillo Gallery, Florida.

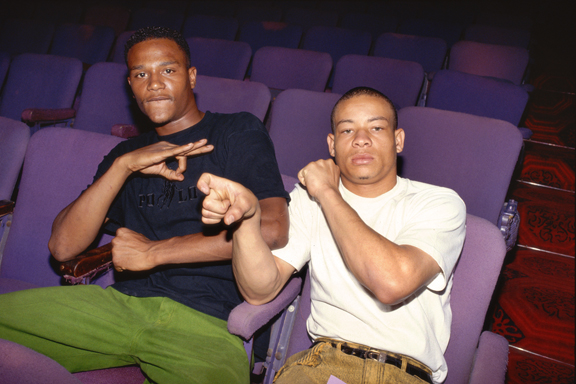

©Lyle Ashton Harris, Truce Between Crips and Bloods, Los Angeles 1992. Courtesy of the artist and David Castillo Gallery, Florida.

©Lyle Ashton Harris, Truce Between Crips and Bloods, Los Angeles 1992. Courtesy of the artist and David Castillo Gallery, Florida.

©Lyle Ashton Harris, Lyle and Tommy, Venice, 1992. Courtesy of the artist and David Castillo Gallery, Florida.

©Lyle Ashton Harris, Lyle and Tommy, Venice, 1992. Courtesy of the artist and David Castillo Gallery, Florida.

The central act of this exhibition is an act of self-appropriation and self-curation: a 50 year-old artist turning to the work 20 year-old self and imbuing it with coherence and importance. It is fairly evident that most of the images at the time of their being taken were not intended for an art gallery, they seemed to be simply a personal documentation of the artist’s friends and surroundings. What is produced from the act of selecting pictures meant for personal use and putting them in a gallery is a conversation, or collaboration, between two artists at two stages of life. During the period these pictures were taken, Harris, freshly emerged from the California Art Institute, was probably, like most young artists, eager, hungry, and anxious to assert his voice. Revisiting them from the perch of age and experience, after his place in the art world has been established, the artist has more of a sense of which images have meaning outside of sentimental value. It is a performance of memory. The act of remembering is always subjective and selective, and it involves bringing disparate memories into concordance with one’s current sense of self. The word “recovering” in the title of the series can be taken in the sense of re-collecting. Here, Harris constructs a self-portrait that is more complete because it's coming from two perspectives, one older and one younger.

©Lyle Ashton Harris, Gail and Peggy, Ft. Greene, Brooklyn, New York, Circa Late 1980s. Courtesy of the artist and David Castillo Gallery, Florida.

©Lyle Ashton Harris, Gail and Peggy, Ft. Greene, Brooklyn, New York, Circa Late 1980s. Courtesy of the artist and David Castillo Gallery, Florida.

©Lyle Ashton Harris, Nan, Berlin, 1992. Courtesy of the artist and David Castillo Gallery, Florida.

Neither appropriation nor self-appropriation are new techniques for Harris. His installation, “Blow Up IV,” features a blown up image of a Adidas ad framed by a collage of other appropriated images, which include Harris’ own artworks from previous series. Here, appropriation brings the underlying politics of the image to the surface, which also applies to the Ektachrome series. Many are seemingly innocuous snapshots, but the fraught political context of each are foregrounded in the artist’s act of appropriation. One such image is of performer M. Lamar in a bathroom at the Yurba Buena Center for the Arts. Seeing Lamar, dressed in drag, next to a conventionally dressed man, one is made aware of how the communal bathroom marginalizes anyone whose interpretation of gender is loose. Harris builds up a series of such moments where scenes from everyday life point to a larger context. Harris’ work is often political, and while it is also often personal, it is rarely as intimately, unreservedly so. It is by focusing on his own personal growth as an artist and as a person that Harris hints at an experience more universal. This series is a story of a young artist’s discovery, and an older artist’s rediscovery, of his identity.

©Lyle Ashton Harris, M. Lamar, Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco, 1993. Courtesy of the artist and David Castillo Gallery, Florida.

©Lyle Ashton Harris, M. Lamar, Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco, 1993. Courtesy of the artist and David Castillo Gallery, Florida.

©Lyle Ashton Harris, Lyle, Gay Pride Parade, San Fransisco, 1989. Courtesy of the artist and David Castillo Gallery, Florida.

©Lyle Ashton Harris, Lyle, Gay Pride Parade, San Fransisco, 1989. Courtesy of the artist and David Castillo Gallery, Florida.

by Conor O'Brien