Carving the Epic: Interview with Robert Longo

Image Above: ©Andrea Blanch, Robert Longo.

STEVE MILLER: What’s it like to draw the Cosmos? Not many people have the balls to draw the cosmos.

ROBERT LONGO: I realize I am interested in an ability to see these inaccessible objects. It goes back to death. I have this fantasy that when I die, and my soul is floating out there, I’ll get to see the Earth. I’ll get to see the Moon, the stars. Then, I said why the fuck wait? I’ll do it myself. I want to make the stuff I can’t see.

For the past several years, I have been thinking about how, as artists, we are blind. We can’t see how other people see our work. It's the same thing that drives us: to make things that we can’t see. The only real way we can see them is by making them. It’s really very hard to explain to someone the compulsion, and the desire, and the obsession to make work that is driven by this desire to make things that we can’t see.

I remember the experience of producing the first Earth that I made. It felt as if I was out in space looking at this glass ball. It made me go back to Hieronymus Bosch’s doors of The Garden of Earthly Delights. When you close the doors of The Garden of Earthly Delights there is, painted on the back of the doors, an image of a glass ball that has a flat Earth in it, which I think is amazing.

For one of the big star fields that I created, I first projected a Jackson Pollock painting over the paper’s surface. I then sketched the basic structure of the Pollock painting, and then projected a nebula on top of that. I basically made Jackson’s nebula. I kept thinking of this idea of intelligent design: trying to play God in a way.

Image Above: ©Robert Longo, 'Untitled (Jackson's Nebula),' 2006 / Courtesy of the Artist

SM: Pollock said, ‘I am nature.’

RL: I know. I thought about that so much. His paintings are really quite profound in that way.

These are images that we want to see because the only way that we’re going to see them is when we’re dead – or at least that’s when we think we’re going to see them. We grew up during the first time there were images of the Earth from the Moon. That was incredible to me, the idea that these guys could see the shape of the Earth, and see how round it was. As a kid, I remember once at the beach, I swear I could see the curve of the Earth. I swear I could see the horizon. It’s not there but I still pretend I can see the curve of the Earth.

SM: This issue is about science, and I think that the reason that I really got into thinking about you for this was because of the bomb series from 2003 that you titled 'The Sickness Of Reason.'

RL: Science is interesting because we want to believe in it. We used to believe that science and technology would save us. Now we’re starting to think it’s going to kill us. The difference between our generation and the generation of my kids is that we dealt with nuclear or atomic threats, while they are dealing with bio-genetic fear. It’s really radically different, the idea of redesigning us, where the interface between man and machine collides.

My bomb series, Sickness of Reason is inspired by Goya’s The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters. Actually, one of the bombs that I made looks a lot like Goya’s painting The Colossus. I always thought that looked like an atomic bomb. I find I try to make art as if I am tuning an old radio: if I turn the knob too much one way or another, I lose it — it’s really important that I find this balance between something that’s highly personal, and at the same time socially relevant. And if I can find that balance, it makes sense for me to investigate it.

Each series leads me to the next. Before the drawings of bombs, I was making wave drawings. Then 9/11 happened, and I started incorporating the smoke from 9/11 into the drawings. Someone sent me an image of the towers falling down, and when I printed the image, it came out of the printer upside-down. I thought, “The image of the buildings beneath the cloud of smoke looks like a bomb! Holy shit!”

I remember showing the atomic bomb test images to my kids. I asked my son who was 8 years old at the time, “So, what do you think this is?” And he answered, “I think it’s a hurricane.” He thought they were nature.

All of a sudden, I had this idea of man trying to be nature; an arrow pointed to go in that direction. I dropped my work on the waves, and the bombs happened. The Russian test bomb was a really great image. It was such a dirty, nasty-looking bomb. It looked like they blew it up in a fucking coffee can. With my work, I ended up beautifying certain images. The bombs led me to roses. Waves, bombs, and roses have a similarity in those early series because they all exist at a moment of being. It’s almost like they’re orgasmic. I mean, they’re all at the moments of becoming.

I started to understand that with the waves, the shape of a wave is not necessarily dictated by how strong the wind is. It’s dictated by what’s deep underneath it. It’s like psychoanalysis. Ironically, before the wave drawings, I was working on the Freud Cycle drawings.

Julian Barnes who wrote an essay about the idea of the artist turning catastrophe into art in Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa, which is really interesting.

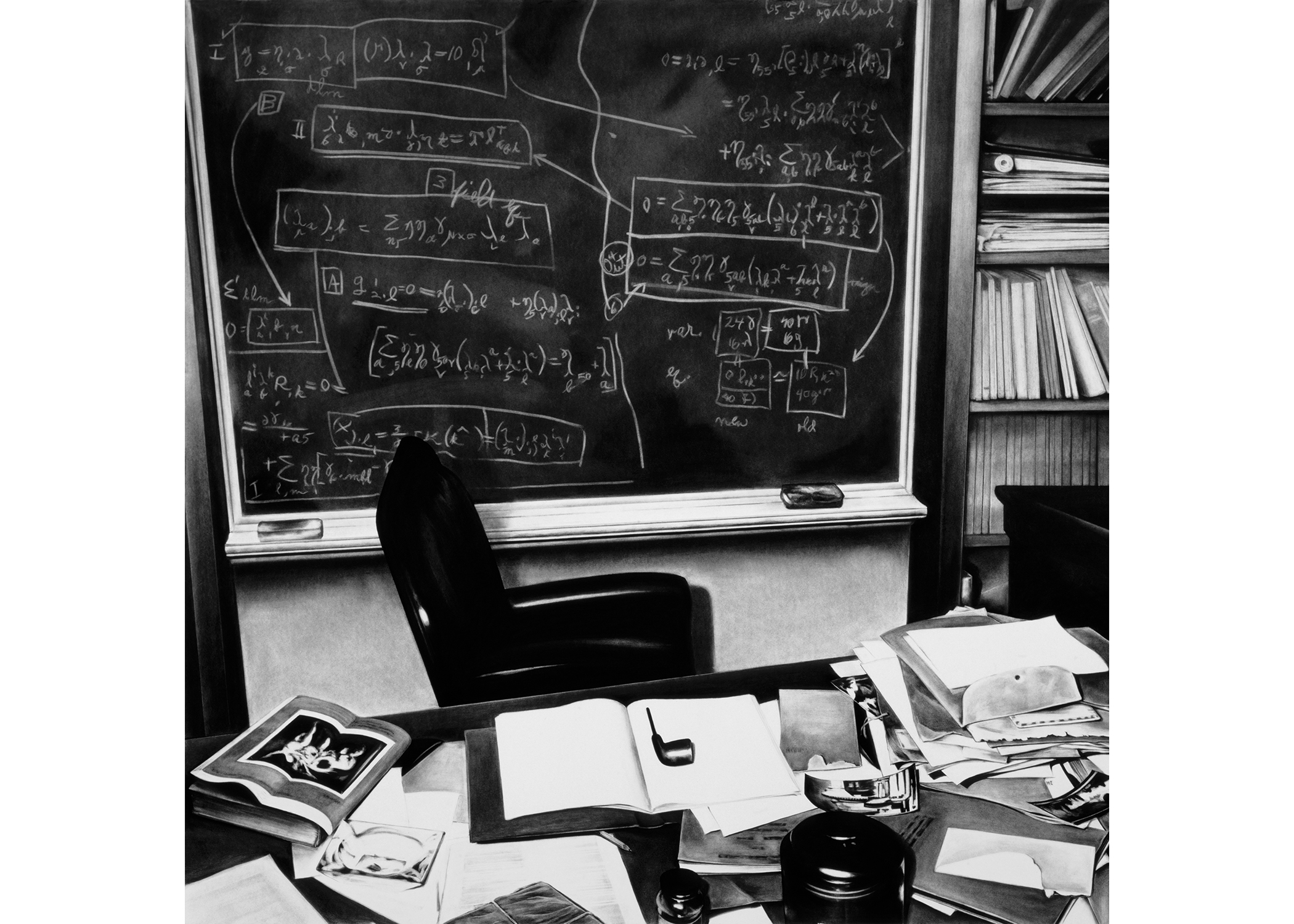

In the summer of 2004, I was invited to the Aspen Institute for Physics for the 100th anniversary of Einstein’s Theory of Relativity. They wanted to show a group of seven bombs with the drawing I did of Einstein’s desk. The institute showed these drawings in an octagonal room, a room in which they then hosted a conference about nuclear proliferation, with military people, scientists, and politicians. I thought that was very ironic.

Image Above: ©Robert Longo, 'Untitled (Russian Bomb / Semipalatinsk), 2003 / Courtesy of the Artist

SM: In regards to the bomb images, you understand where they’re coming from, and the research that went into defining them. I do want to talk about photography, because that’s one of the issues here. I want to talk a little bit about the content. Death is one of the major themes in your work. There is beauty, and there is death. There is power, and there is spectacle. All of these things are operating, on a complex level simultaneously. Some of the images are coming from LIFE magazine, so it’s kind of like pop culture.

RL: In considering all of those subjects such as beauty, death, spectacle, and power, there is only one subject that encompasses all of them: The Epic. I grew up with The Ten Commandments, with Spartacus, and The Longest Day, all of these epic movies. I think this is another force that drives me: trying to make epic work. I’m looking for the kind of rush that I had when I saw those movies.

Fear of death is why most of us make art, anyway. Hanne Darboven’s work, with all that counting, possesses a subtext of, “I’m alive, I’m alive, I’m alive…”

The fact that I make these drawings out of charcoal is in itself quite profound, because it’s a mourning material. It’s burnt. It’s dust. They’re incredibly fragile. I mean, I make the most fragile art out there. When I saw Herzog’s film Cave of Forgotten Dreams, I thought about how those charcoal cave drawings are thirty-thousand years old! We are all fighting against death. We are trying to deny death, to look it in the face and say I’m not scared. Say, “Fuck you, I’m gonna live forever.”

SM: The reason why it’s doubly interesting, in terms of your work is 1) in your use of black and white, and 2) in regards to a quote by Roland Barthes: “Photography may correspond to the intrusion, in our modern society, of an asymbolic Death, outside of religion, outside of ritual, a kind of abrupt dive into literal Death. Life/Death: the paradigm is reduced to a simple click, the one separating the initial pose from the final print. With the Photograph, we enter into flat Death.”

RL: That flat death is really great.

SM: It’s you. Why do you relate to it so much?

RL: My son once asked me why I make work in black and white. I remembered looking at LIFE magazines: The color Exposées would be of Marilyn Monroe, the circus, Broadway shows. Then when you would come to the photojournalism of the Vietnam War and the horrors of Calcutta they were always in black and white. Maybe in my mind I’ve come to the point of thinking that the truth is black and white, but I also think it’s highly abstract in that sense.

SM: These drawings flat line photography. Photography in itself is a flat line of the image which it captured, which was alive.

RL: I think my “Men in the Cities” drawings played off of the art of shooting a photo. I remember when I got a motor drive for a camera. I would shoot 30-40 photographs to get one image to make a drawing. It was like I was shooting these people, literally. I work from photographs that are taken from a split second. I construct these images. I draw them; I build them. It takes an incredibly long time to make a picture that is based on a split second. The anti-Robert Smithson. Entropy in reverse.

There’s traditional representation and modern abstraction. I exist somewhere in the middle. Maybe, I translate photographs. I remember how my father would remember things through photographs. Photographs function as our collective memory. They fuse into this sense of our collective unconscious. They are surrogates of ancient archetypes. Our memories exist as photographs, with potentiality as opposed to actuality.

SM: I’m looking at your tools. You have a brush, the eraser to dig. It’s like an archeological excavation.

RL: I graduated with a sculpture degree. In my mind I am a sculptor, not a painter. These drawings are truly sculptural. The process of these drawings is the opposite of traditional painting. Traditional painting works from dark to light. I work from a white surface. The white in the drawings is always the raw, virgin paper. I never add white to the drawings. The drawings get built up with so many layers of charcoal and dust and powder and stick. The way the drawing comes to life is by erasing, carving the image out of it.

You have to realize the depth in which you can go; if you fuck the paper up, you can never get it back. They’re like mineshaft disasters where you can never get back to white.

We make different kinds of erasers. When we made those abstract expressionist paintings we made erasers to imitate the grain of the canvas for the Barnett Newman. I’m dealing with a minor, forgotten medium that I found in the crack of high art. I basically had to re-invent drawing. We have invented techniques with the powder, and we’ve learned, what I call, different colors of charcoal. Painting to me, I realize, is a form of architecture. You really have to build a painting. Great masters, how they deal with paintings, how they seam together wet and dry blows my mind. My drawings take a long time, but great paintings take fucking forever.

Image Above: ©Robert Longo, 'After Pollack (Autumn Rhythm: Number 30, 1951),' 2014 / Courtesy of the Artist and Metro Pictures

SM: Your work for me is really about a conceptual practice. Even though there is imagery, the approach is conceptual. Compared to the Abstract Expressionist painting you worked from, your drawing is not a "reproduction." It’s of equal value, in terms of the experience for the viewer. Was this a part of your intellectual thought process or sensibility?

RL: I think, for me, the ‘Picture’ sensibility was there at the beginning, but it’s definitely not there anymore. For me, Abstract Expressionism is a force in my life like the ocean. In a weird way, my drawings based on Abstract Expressionist paintings from my 2014 exhibition “Gang of Cosmos”, were definitely labors of love. Regarding authorship, I thought maybe I was revisiting the Abstract Expressionist works to redeliver the authorship back to the artists who made those paintings.

If you are successful enough to create an archetypal image in culture, you eventually lose authorship. So ‘Jackson Pollock’ could be the style of painting that somebody does their bathroom in. The authorship is lost in that work. By doing these drawings I was reinstating the artists’ authorship. The time it takes to make a brush stroke versus the time it takes to paint a brush stroke is radically different. Black and White photography is very arbitrary. So I worked from color photographs, and deliberately tried to do a translation into black and white with as much sincerity as possible.

In the Joan Mitchell painting I realized there was black and red next to each other, and in the black and white photograph they looked exactly the same. So how do I translate that to give it some soul? Each painting required a different kind of strategy.

For instance, what was really interesting, with the Pollock, is we toned the whole paper grey, and then we projected the painting onto it, and then we drew the black first. Once you draw the black first you realize there is clearly a plan involved with Pollock’s Autumn Rhythm (Number 30). It was basically divided into three sections. The next thing we did was the green and the gold, with different values of powder. The last thing we did was the white, with erasing. It was this really weird deconstruction of the painting to make it come alive. What was also amazing was with this idea of fractals: you could tell how tall Pollock was and how much he weighed by his gestures. It was really quite amazing taking these things apart. In the studio, each drawing looked like a forensic sight. We got permission from all of the artists’ estates. We got into the museums to see all the paintings. We took about 100 photographs for every painting. So every drawing was surrounded by hundreds of photographs that we were working from to reconstruct this drawing.

SM: So obviously there is subjectivity in the translation, but the subjectivity is like a technical virtuosity. How are you making these decisions? All intuitively?

RL: Yeah. Very much so. Ironically, now that you bring that up, if art is subjectivity then science is objectivity. The choices I made were somewhat on the fly, but were highly educated ones. They were planned.

My work also has the scale of Abstract Expressionism. I’m definitely a child of the Abstract Expressionists. That scale. My generation of artists, the ‘Pictures Generation’ for lack of a better name, I think we wanted to compete with the mediums that shaped us. That’s why I wanted to make a movie. The one big difference between cinema and an artwork is, how many times have I looked at The Raft of the Medusa in the Louvre versus how many times have I watched The Godfather? Art has this incredible democracy that exists within it that is not dependent on the narrative structure of film. When they first invented film they thought it was useless. Then writers thought, ‘This is going to put us out of business, so we better usurp it, and put it into a narrative structure with a beginning, middle, and an end.’

With an artwork, the viewer makes his own story. You can look at an artwork narratively, however you want to look at it. That’s why I don’t like time-based art. I find it really boring. I hate going to movies where I miss the beginning of a movie. I don’t want to walk into a gallery wondering, ‘When does this start?’ I like the democracy that exists within art.

SM: I think you have a rather scientific mind because of the research that goes into your work. What I perceive when I look at a lot of your work, is that it’s through the lens of science. Then when I look at these x-ray drawings I’m insanely jealous because it’s such a great idea. We’re talking about rendering something visible that’s invisible. What’s that experience for you as an artist?

RL: The first drawings I made that were based on x-rays, were based on x-rays of Rembrandt’s paintings of Jesus. I think God is about believing in the invisible, and x-rays are about seeing the invisible. When I began this series, I re-read texts by writers such as Walter Benjamin, who describes the loss of the aura. I thought that this series of works based on x-rays was a way of reclaiming the aura. I also love this idea of seeing things that you can’t see.

Bathshebaat her Bath is a really good example. She’s been asked by King David to come over to his house while her husband is away fighting for King David, because he wants to fuck her. She gets pregnant. King David calls her husband back, but he doesn’t want to sleep with her because he feels bad for his troops, so he sleeps out on the street. King David freaks out, sends her husband back to the front. Her husband dies, and David takes Bathsheba as a concubine. In the finished painting she has such incredible, tender, poignant resignation in her face. But in the underpainting, the look that she has is more like, ‘Hmmm, this could be kind of interesting. I get to do the chief’. When I saw that x-ray I was like holy shit, this is a completely different story. The interesting thing is that there are stories behind making this work, then there are the stories that people perceive from it. I find that really interesting.

The Raft of the Medusa is another perfect example; the aristocrats cut the rope on the raft and let them float, and these fifteen survivors, out of the 150 on the raft, go back to Paris and tell everyone that these loyalists fucking just let them drift. There was almost a revolution because of this. Many viewers don’t know this story of The Raft of the Medusa, but they imagine their own story. It’s really interesting in that sense.

Image Above: ©Robert Longo, 'Einstein's Deks (Princeton),' 2004 / Courtesy of the Artist

SM: In those atomic bomb drawings, you included Einstein’s office. A lot of artists have had a fascination with the site of where science takes place. It’s either the lab, or the chalkboard. What were you thinking by including that with the bomb drawings?

RL: Right. There was Einstein’s office. There was a rocket taking off, which I included as an homage to Jack Goldstein, because Jack had just died. There was also a shot of the corduroy effect of the waves, which reminded me of a movie I saw as a kid, On the Beach. I had just finished doing the Freud drawings, about Freud’s office. I realized that Freud and Einstein are these incredible white, old men bookends of western civilization. I found this photo of Einstein’s that was taken the day he died. I found out that his office at Princeton was the same office, same space, in the kind of cupola or the dormer of the building, the exact same office as Oppenheimer’s office. So I took the chair from Oppenheimer’s office and put that chair into Einstein’s office.

Then I tried to understand what was written on the blackboard. I learned that Einstein’s whole life, after the theory of relativity, was this attempt to unify string theory and the theory of relativity. The blackboard was literally divided in half. There were these two formulas. The problem with the original photo of Einstein’s office was the information on the blackboard was unclear, so I took the homework of my son, who was doing trigonometry, and wrote it on a blackboard. So part of it, on the blackboard in Einstein’s office is my kid’s math homework. What was really funny was when we showed the drawings in Aspen, there were guys there that actually knew Einstein and were looking at the blackboard going, ‘What was he fucking thinking?’

From Museé Magazine's March 2016 Issue "Science."