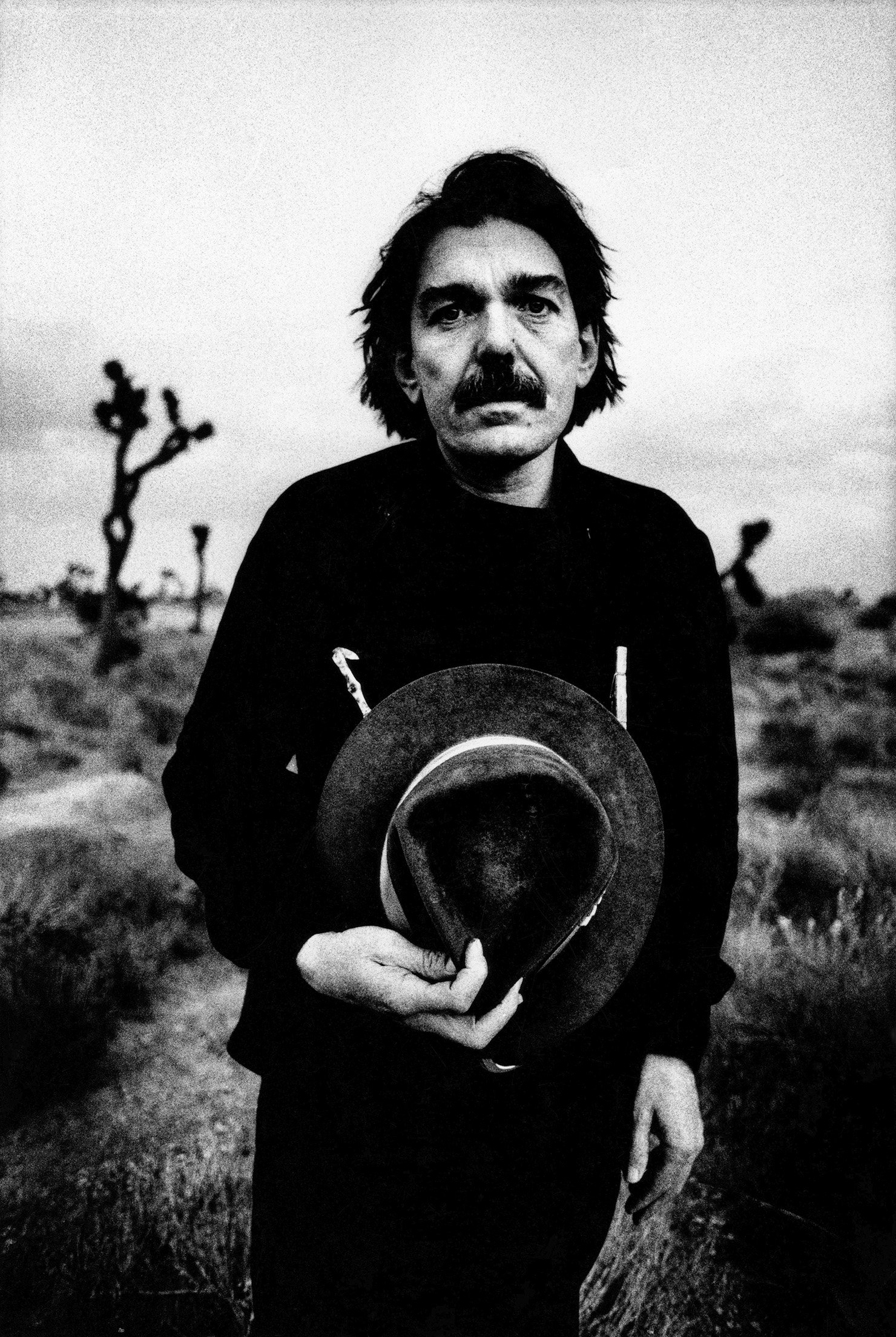

Anton Corbijn: Unexpected Moments

Portrait by Stephan Vanfleteren

For decades, Anton Corbijn has shaped the visual stories of music and film icons. From Depeche Mode to Joy Division and Nirvana, he's captured the essence of legendary artists, not just visually, but intimately. In this exclusive interview, we explore Corbijn's journey, collaborations, and the unique dynamics of his work. Starting at New Musical Express (NME), he rapidly honed his skills before creating iconic music videos. We uncover behind-the-scenes stories, his nomadic lifestyle, and the delicate balance between art and relationships.

Andrea Blanch: I'm curious about your career because it's lasted for so long. I always admire people who have such longevity, and you seem to have been able to maintain it. What do you attribute that to? Is it the diversity of your work? Besides your talent, I mean, it's not easy to have such staying power.

Anton Corbijn: Well, no, not really. I've always approached my work with a certain mindset. I tend not to have grand expectations, which makes everything that comes my way feel like a pleasant surprise. I'm quite hands-on, and I prefer not to have an extensive team, which helps keep my expenses in check. While I appreciate well-paying jobs, I don't feel compelled to pursue them relentlessly. Variety and change are essential to me; I strive to avoid repetitive photography. Even in photoshoots, I prefer to keep things concise rather than dragging on for half a day. Being relevant in the constantly evolving world of photography is a challenge. Over time, I've experimented with different formats and techniques, from black and white to a unique printing process I called "lit prints." I switched to Hasselblad, which required rethinking my compositions. Later, I explored paparazzi-style pictures using Polaroid film with flash, followed by a series of self-portraits using various film types. It's essential to keep things fresh and engaging for myself. Presently, I use both analog Hasselblad and digital cameras, along with my trusty iPhone. I did a book with just pictures of my iPhone from the last 10 years, it's called Instanton, and it's a lovely little book, but in a way it's quite open about how you live, you know, you always have your camera with you – if you have an iPhone – so you tend to take a lot of private pictures with it, and so, in that way, the book is quite open in that sense.

Anton Corbijn, Pj Harvey, New Forest, 1998. ©Anton Corbijn

Andrea: So, what's the difference, in your opinion, between shooting for a client in Europe and shooting for a client in New York? Because I'm just curious about what you say about trying to keep it small, and my experience has been in America that they like big production. They think if you don't have a big production, it's not as serious, so I'm curious if you've had the same experience.

Anton: Yes, there's definitely an expectation for a kind of circus act, and personally, I'm not a fan of that approach. I believe that excess equipment and unnecessary personnel often get in the way. Even when I'm shooting digitally, I tend not to have a laptop connected on set because there's nothing for others to see. I recall a particular experience around 2006 or 2007 when I was working on a shoot for HBO, creating the poster for the final series of "The Sopranos" with James Gandolfini and the Statue of Liberty in the background. HBO had flown in a team from LA, and there were around 20 people behind me, while it was just James Gandolfini, me, and one assistant in front of the camera. I felt quite uncomfortable with such a crowd, so I politely asked them if they'd like to watch on the monitor. They agreed, and as they walked away, I thought, "Great, now where's the monitor?" It turned out there wasn't one, but it seemed like a good way to have some space for the shoot. I never got a job from them again.

Andrea: And what do you do when you're shooting a film and there is a much larger crew?

Anton: Of course, that's quite a different scenario. Working in film is a unique experience. For one, you're working with actors, and they're trained to perform even when there's a sizable crew around. Making a film requires a team; there's no way around it, and in many ways, having a team can make the process smoother for everyone involved. However, photography is often a one-on-one interaction, so I'm usually quite bothered when there are too many people around. Typically, the most I'll have on a photography shoot is two assistants

Anton Corbijn, Miles Davis, Montreal, 1985. ©Anton Corbijn

Andrea: Do you find one medium more satisfying than the others? I imagine each has its unique appeal. What distinct forms of satisfaction do you derive from photography, film, and music videos? Are there notable differences in how they affect you? Music videos seem to be a comfortable fit for you.

Anton: I've moved past that phase a bit. I've explored that world quite extensively, and I'm uncertain if there's anything groundbreaking left to contribute. Film, on the other hand, remains an ongoing adventure. It's undeniably demanding yet incredibly rewarding because it allows for wider sharing. The learning curve in filmmaking is substantial, and the extended time in one location is refreshing. Photography typically involves just a few hours in a place, leaving behind fragments of memory. But when I recall my experiences in America or my time spent in Italy near Rome, particularly Abruzzo, the memories are vivid. The bonds formed with the people I collaborate with in filmmaking are unique and delightful compared to photography, which still offers the allure of simplicity. When I'm out photographing on my own, it's just me and my camera, a straightforward process. Photography isn't particularly challenging.

Andrea: Film is more complex for sure, you have to spend more time with it. What about fashion photography? I didn't know that you do fashion photography. And I opened up a Vogue, and I saw your pictures. So how do you feel when you're doing that?

Photography is often a one-on-one interaction

Anton: Initially, I didn't know what to do with beauty. Working with beauty was a challenge for me; I was very insecure. So I was always looking at the beauty from the inside, making photographs that make people look interesting, rather than so-called beautiful. And so it took a while for me to photograph models. I never knew what to add to it, because they were already so beautiful. So I didn't know what my function could be for that. I didn't know what to add. And that changed a bit when I started to meet models, and they became people for me. And then I photographed them. I often photographed models in the nude because I wasn't sure how to incorporate clothing into my work. Fashion and clothing gradually found their way into my photography, especially when I began working with musicians who had stylists and specific outfits to convey their expressions. While I wouldn't classify myself as a fashion photographer, I do capture people wearing fashion from time to time, which led to my book "MOOD/MODE" a few years ago. Currently, there's an exhibition of this work in a museum in the Netherlands, starting shortly before Christmas.

Andrea: And what about Switzerland, the film that you're doing with producer Gabby Tana? How do you see that?

Anton: It's an exciting project for me, especially since it's the first film where a woman takes the lead among the few films I've worked on. To work with Helen Mirren has been fantastic, and the story is really good. So, it's definitely an adventure. It's been nine years since my last film. The first four films I did were quite fast, one after the other. I feel happy with them. There's no shame or regret. Sometimes, when I watch them, I might think about possible improvements, but that's just part of the creative process.

Anton Corbijn, Johnny Cash, Nashville, 1994. ©Anton Corbijn

Anton Corbijn, Mick Jagger, Glasgow, 1996. ©Anton Corbijn

Andrea: Certainly. It is. I feel that way, too. Would you say that your aesthetic evolved through experimentation and that it continues to shape your work today?

Anton: I've noticed that these days, I'm less experimental than I used to be. Part of it is because I no longer print my own pictures. When you're actively involved in the printing process, you're naturally inclined to experiment more. However, due to health concerns regarding the fumes, which aren't good for my lungs, I've had to stop printing. To be honest, I'd like to be more experimental right now.

Andrea: Do you ever think about AI? What's your feeling about it?

Anton: No, I'm not inclined to go in that direction. I truly appreciate the element of human error, human mistakes, and human imperfection in my work. I've never used it, and I get the sense that even if you want to make it appear human, you have to instruct it to do so. I believe real mistakes should be genuinely human mistakes, not just a computer glitch, an AI command, or the like. Although, I'm sure AI has its merits in certain areas.

Andrea: As a visual artist, you've mentioned your desire to be close to music, which led to your work on music videos starting in 1972. Can you share your process for translating the essence of sound and emotion into a compelling visual image?

the beauty in many of my works lies in the imperfections

Anton: Well, if I knew that properly, then I'd be a very rich man, but I don't know. Each project is a new thing for me, and I approach it by contemplating what would best complement the music and the individuals involved. I work a lot with the same people, and that helps because you know kind of their thoughts, and motivations, and you don't have to be introduced to them every time, so there is like a family kind of vibe. And I think that works well.

Andrea: While working with artists like Depeche Mode or U2, does the creative process typically involve them presenting you with an initial idea, playing music for you, or engaging in a dialogue about the visual concepts? How does this familial and long-standing collaboration unfold?

Anton: The dynamics of collaboration can differ from one artist to another. In many cases, I have the opportunity to listen to the music first, which can be crucial when working on album covers, as having a title and the music can spark my creative process. Sometimes, the artists themselves have initial ideas, and with Depeche Mode, it usually comes from me. When it comes to U2, it's more of a collective effort, with ideas emerging from the band, and I work to fine-tune and enhance the concepts. It's truly a collaboration, so we all come up with something. But I remember that for "No Line on the Horizon", I think they wanted to do the photoshoot in Southern Europe. I suggested Dublin. Because that's where they’re from, and it shows you many years down the line how far you've come. So we did it there, a very down-to-earth shoot because it was shit weather. And they probably regretted listening to me, but there were some strong pictures there, they're not sunny, and they're not so commercial, but they are good for people who love the band.

Anton Corbijn, Captain Beefheart, Mojave Desert, 1980. ©Anton Corbijn

Andrea: Can you share a story, like an anecdote from one of your shoots with U2 or Depeche Mode? Something that you found particularly challenging or amusing?

Anton: The only one that comes to mind, though I'm not sure how captivating it may be, is from a shoot with U2 in Amsterdam where they were on bicycles quite some time ago. Initially, nothing remarkable was happening; it was like a non-picture. Out of impulse, I dropped my trousers right on the street. To my surprise, it sparked laughter from the band, and suddenly, we had a much more engaging picture.

Andrea: So, how has the business landscape changed for you throughout your extensive career? Have you adapted to these shifts or maintained your approach?

Anton: The business has indeed evolved over the years. What I've noticed is that there are fewer magazines available to be published in now compared to earlier in my career. I personally enjoyed publishing in magazines because it allowed people to come across my work by chance. Instead of relying solely on print, I've started using Instagram to share my photos. However, I'm not a big fan of social media. I tend to publish irregularly, unlike some who post multiple times a week. It's time-consuming, and I prefer not to get too caught up in it. I don't use TikTok or Facebook anymore either. It's interesting how everyone today seems to consider themselves a photographer, leading to a saturation of the field. There are many photos being created, but not all of them are particularly captivating. However, among this deluge, there are still young and talented individuals emerging, full of energy and unafraid to break the rules, and that's always intriguing.

Anton Corbijn, Bruce Springsteen, New Jersey, 2005 ©Anton Corbijn

Andrea: Throughout your career, have there been instances where unexpected accidents or unplanned elements played a significant role in the final outcome of your work? Could you share a memorable example?

Anton: Over my career, a lot of unexpected moments and accidents have contributed to the final outcome of my work. If I were to summarize my whole career, I'd say it's been one long sequence of such moments. But to share an example, there was a shoot I did with Garland Jeffreys, the American artist, who's truly fantastic. We collaborated on a few album shoots. One time, in 1980, I was in New York, and he asked me to create an album cover for his "Escape Artist" album. I inadvertently loaded the same film twice in my camera, causing double exposures to occur haphazardly, but not in a deliberate or neat way. It was entirely accidental footage, yet one of those pictures turned out to be the album cover.

Anton Corbijn, Björk, Reykjavik, 1999. ©Anton Corbijn

Andrea: "Enjoy the Silence" is considered an iconic music video. Could you take us through the creative journey of that video, from initial concept to final production, including the choice of film and any unique challenges you encountered during its creation? Were there any remarkable interactions with the band during the process?

Anton: The "Enjoy the Silence" music video was my sixth video for Depeche Mode, and it was part of their "Violator" album. It was a departure from my earlier videos because I started shooting in color, yet I still used Super 8 film, which allowed me to film it myself in a low-key manner. When I presented my original idea for the video to the band, it involved a king with a deck chair searching for peace, all set to the song. The band, however, didn't quite like the idea initially and thought it was silly. But they believed in the song and asked me to return with a new concept. I couldn't come up with anything different and insisted on the initial idea. At the end they agreed to proceed with it, and we kept the videos on a tight budget of around £20,000. We filmed in Portugal, Switzerland, and Scotland, and even did some work in my studio with the entire band. What made these videos unique was the low pressure from record companies, allowing us creative freedom.

Andrea: Did your early involvement with NME significantly impact your early career, and in what ways did it influence your artistic journey?

Anton: My time at NME did play a crucial role in shaping my early career. I was already working for a similar magazine in the Netherlands during the '70s. By the time I came to England in the late 1970s, I had considerable experience in publishing and creating album sleeves. NME appreciated my work and hired me for a few minor assignments. Then, when a photographer fell ill, I got a chance to tackle a more substantial job, leading to my becoming the main photographer for NME a few months after I arrived in England. This lasted for a solid five years, and it was an incredible learning experience. It allowed me to meet a variety of artists, including U2 and Depeche Mode, among others. It was a dynamic environment, with a high turnover of assignments due to the magazine's weekly schedule, which meant we had to produce a lot of content consistently.

Anton Corbijn, Ai Wewei, Beijing, China, 2012. ©Anton Corbijn

Andrea: So you had to be fast.

Anton: Indeed, working at NME required me to be fast. We had to produce a lot of content every week. While the pay wasn't substantial, I lived great, initially in a squat in London and later in an affordable flat.

Andrea: "Heart Shaped Box" is one of your most iconic works. Could you elaborate on the collaborative dynamic between you and Kurt Cobain? How did his distinct visual identity influence the creation of this piece?

Anton: I met Kurt in a photoshoot. We spent two days taking photos in Seattle, some for Nirvana and some for Details magazine. And you know, we got along well, I liked him a lot. And then Courtney Love was living in Liverpool, and she knew a band I worked with there called Echo and the Bunnymen. And I'd done videos for them. And she told Kurt that, and I sent Kurt a video at his request. And then he asked me if I would do that video for Heart Shaped Box. And then he sent me a whole treatment for it, which was amazing, so detailed. And I changed things in it, but I would say 80 to 85% was Kurt's ideas. He wanted to shoot it in Technicolor, but I think it was no longer possible at the time. So the closest we could get to Technicolor was to shoot it in color, then transfer it to black and white, and then hand-tint every single frame. So that took many weeks. But that got it that really strong color back then.

Andrea: Were there any opportunities or projects that you really wanted but missed out on? Any regrets or things you would do differently if you had the chance?

Anton: As I said earlier, imperfection is part of my work. And if I tried to make it more perfect, I think it would not look like my picture anymore. So yeah, I should have done a lot of stuff differently, especially in the 90s. I felt I lost it for a while. It's difficult when you become successful and get one job after the other. I did a lot of self-reflection. And I kept going back to basics. I think that helped me. A simple picture is trying to retake simple pictures.

Andrea: Did you ever aspire to be a musician yourself?

Anton: I think when I was young, yeah. It seemed exciting, and it seemed exciting from where I came from because I came from an island in Holland in a religious community. My father was a preacher, and it seemed that across the water from the island was a more free lifestyle. That was, I think, in a way facilitated by the music and the hairstyle the early bands had, and it all seemed to spell out freedom to me. So I really wanted to be part of that world, but I couldn't play an instrument. I tried piano, I tried saxophone, I tried drums.

Andrea: Have there been any opportunities or projects that you wished you could have undertaken but ultimately eluded you? Are there any regrets or aspects of your work that, in hindsight, you wish you could have approached differently?

I'm not good with lights. I'm good at recognizing light

Anton: Certainly, like any artist, there are projects that I wish I could have realized or approached differently, particularly in the '90s when I felt I lost my way for a period. The nature of my work is such that imperfection is an integral aspect of it. Striving for too much perfection can alter the essence of my art. The beauty in many of my works lies in the imperfections. Though I may have made different choices along the way, my approach reflects who I am as an artist.

Andrea: It seems like you've traveled extensively throughout your career. How has this nomadic lifestyle impacted your personal life? Balancing personal relationships and a life on the road can be challenging.

Anton: It's a very hard balance. I had a lot of unhappy relationships, I guess. But I managed to combine it now, and I think there's a good balance. I got married last year. I'm very happy with that. And we've known each other for a very long time. It's interesting what you said about traveling because I think that defines my photography a bit. Because a lot of photographers are studio photographers, and they're really good at doing stuff with lights. I'm not good with lights. I'm good at recognizing light. When I'm outdoors, I can see what will make a good picture. But I'm not so good at making that light myself. So I always travel to meet people and travel back. So it's time-consuming. But it's also very interesting because you get much more of the environment of the artist in the picture.