From Our Archives: Collier Schorr

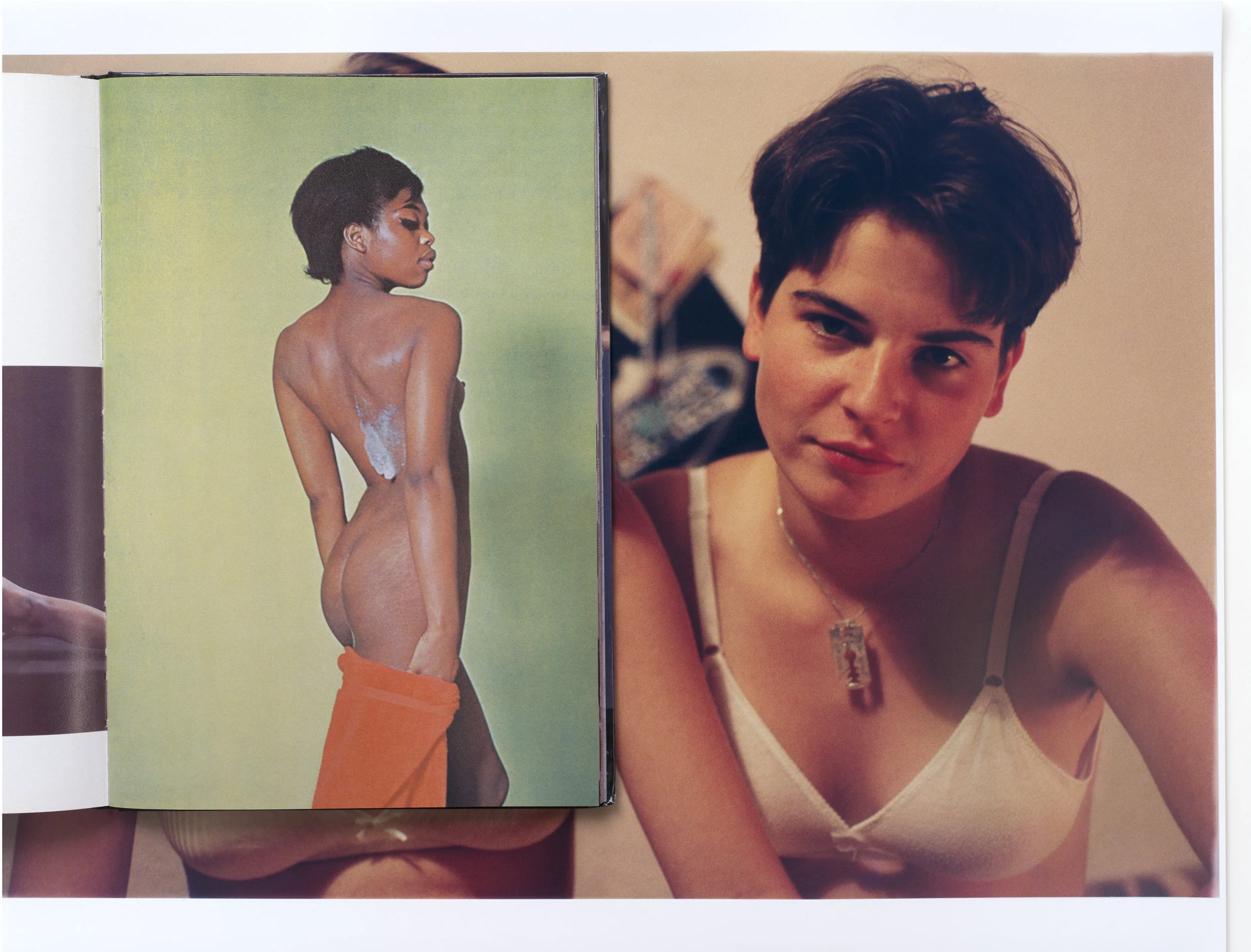

What! Are you Jealous? 1996-2013 © Collier Schorr

This Interview first appeared in our 13th Issue: Women

ANDREA BLANCH: 8 Women is your first book dealing specifically with women. However, you have had exhibitions that focused on women before (Other Women at Modern Art, London, 2006). Why did you decide to publish this book now?

COLLIER SHORR: It’s funny, I did a show titled Other Women years ago in London, and I loved the title. I always thought it would be my ‘women’s book’ title because I’m a product of the early ’80s and “other” was always on our lips. But that show was very focused on the Jens F series of work, which was heavily connected to Andrew Wyeth’s Helga Pictures. In my project, Helga was played by a German boy named Jens until right at the end of the project. Then, I met a woman named Kate who looked ex- actually like Helga. For me, this was a real signal that avoidance of the female figure was not a solution to issues involving representation. Kate was a gateway to women, who for me suddenly became “women,” and not necessarily figures coded as “other.” So Other Women, as a show, was essentially Kate and Jens re-enacting poses that Andrew Wyeth was interested in. For me, that was my kind of education to classical poses. Half the work in my book and show from that time was a fight out of classicism. It’s complicated even for me. That show was a kind of opening of one door and closing of another.

Smoke, 1998 © Collier Schorr

ANDREA: You’ve mentioned before that within the traditional rubric of portrait photography that men seem ‘oblivious and safe’ under the pressure of documentary scrutiny, whereas women are more subject to sexualization and exploitation. Do you consciously seek to address how photography imprints its subject through the photographic gaze? Would using androgynous models be appealing to you in terms of navigating these paradigms?

COLLIER: It’s all very curious. If you shoot men, as I have done for years, you immediately gain attention from gay men who have been carrying the aesthetic torch for men for quite some time, like George Platt Lynes through to Peter Hujar and then Bruce Weber. For gay men, the interest in work is directly correlated to their attraction to the subject. Gay men have spent lifetimes sorting men into types. So there is the beefcake type, the hustler type, the black nude, the Latino hustler, and the Times Square Trick among others. Only recently did I start to find that what appears to be a democracy and an embrace of all skin colors and classes, is really just a very specific kind of objectification with all the nasty issues of power and dominance and general consumption. So maybe I changed my mind, no one is safe from the gaze of the camera. Then again, I always think people are safer in front of me. And I’m not sure if it’s because I’m a woman. Maybe I find my brand of looking ‘soft objectification.’ I love Peter Hujar’s work because you can feel the communication. Maybe as I get older, I am driven by some combination of things. If the model brings an identity, I’m interested. And if they are open to playing a role, I’m equally open. I’m not a huge director. I enjoy watching- ing. Androgyny is really something I’m attracted to as a look, dating to 1981, living in the East Village, and loving the skinhead girls that hung out on Avenue A. A girl who looks like a boy is interesting, but so is a girl who looks like a girl, but is transformed by fashion. Clothing brings so much meaning. They are theatrical props basically. So, anyone can become another kind of figure.

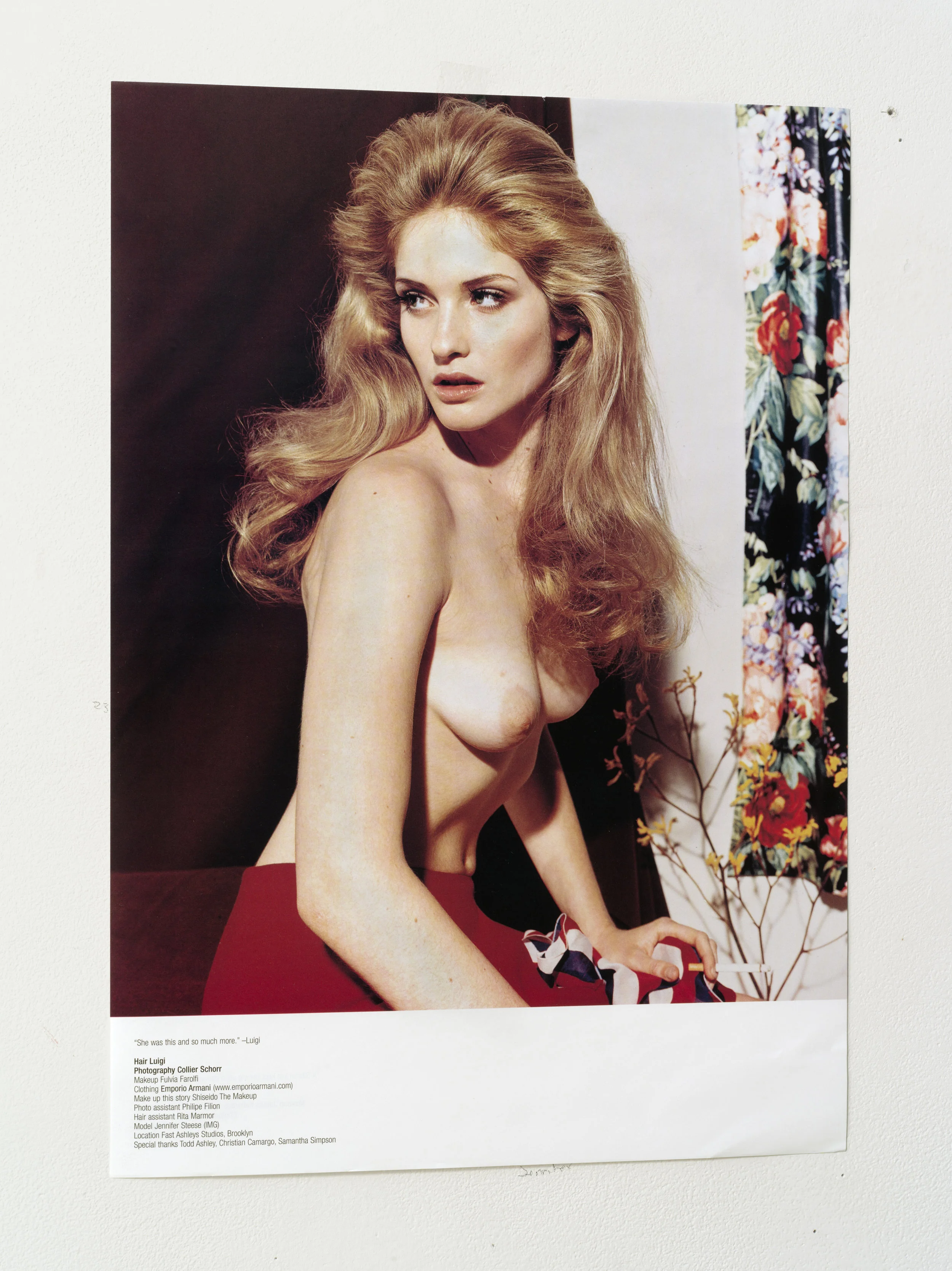

The Business, 2002-2013 © Collier Schorr

ANDREA: You are well known for your work in fashion photography. This collection takes many of your commissioned fashion photographs and puts them in a dialogue with other images. Can you explain this process and what it brings to your practice as a whole? What do you see as the main distinctions between your private work and your commissioned work?

COLLIER: The first fashion projects I did were for Purple Magazine and ID, and they were very much art- ists’ pictures using clothing. It was sort of appropriate at the time. Magazines were starting to look for artists to add something to a discussion and I think it made sense mixing in with the London folks like Corinne Day and Juergen Teller who were definitely doing something on the edge of documentary. After a few shoots with the kids in Germany, I started to work mainly in New York and more within the system of model agencies and stylists. Up until then, I had styled the shoots myself. I would say during this time, there was a lot of separation between my artwork, things I was making for the gallery, the commercial, and things I was making for magazines and advertising clients. It was comfortable for me as I was still working in Germany every summer, so where my art practice was situated was clear to me. In 2009, I stopped going to Germany and I concentrated on fashion. I basically didn’t feel like making art. I didn’t feel like making those decisions about scale and materials. By the time I started contemplating another show, which would become 8 Women, I realized I had all these pictures from shoots that I was obsessed with that hadn’t run in magazines. They were experiments I would make on the side or moments I would take for myself, just to enjoy making a portrait. That’s when I realized that I had been working in a similar way as I had in Germany. As a director of a theatrical troupe that was engaged in scenes and scenarios with professional models, I had consensual partners who were informed participants and who benefited directly from the shoots, which is very different to using kids who have a lesser understanding of what the pictures could look like and no real investment. So, the distinction is really the moment I move my camera left instead of right. It’s the moment I see something I know I won’t give away, but I will keep it for later. But, on an especially free shoot, like a recent project for Red: Edition magazine, I was basically directing as much as I could with a sense that I was making pictures I might show later. The only caveat is that a great picture worth looking at for a longer amount of time, well that happens in an instant. If I do 20 shots in a day and 100 frames for each shot, it’s not as if I will have 20 or even 200 shots. But, I want to keep them and think they say something I want to say. I am happiest when I see something happening I know I will want to explore later. But it is not satisfying if this is at the expense of what makes a good fashion picture for a fashion editorial. I am very conscious of what needs to be immediate and what needs to linger.