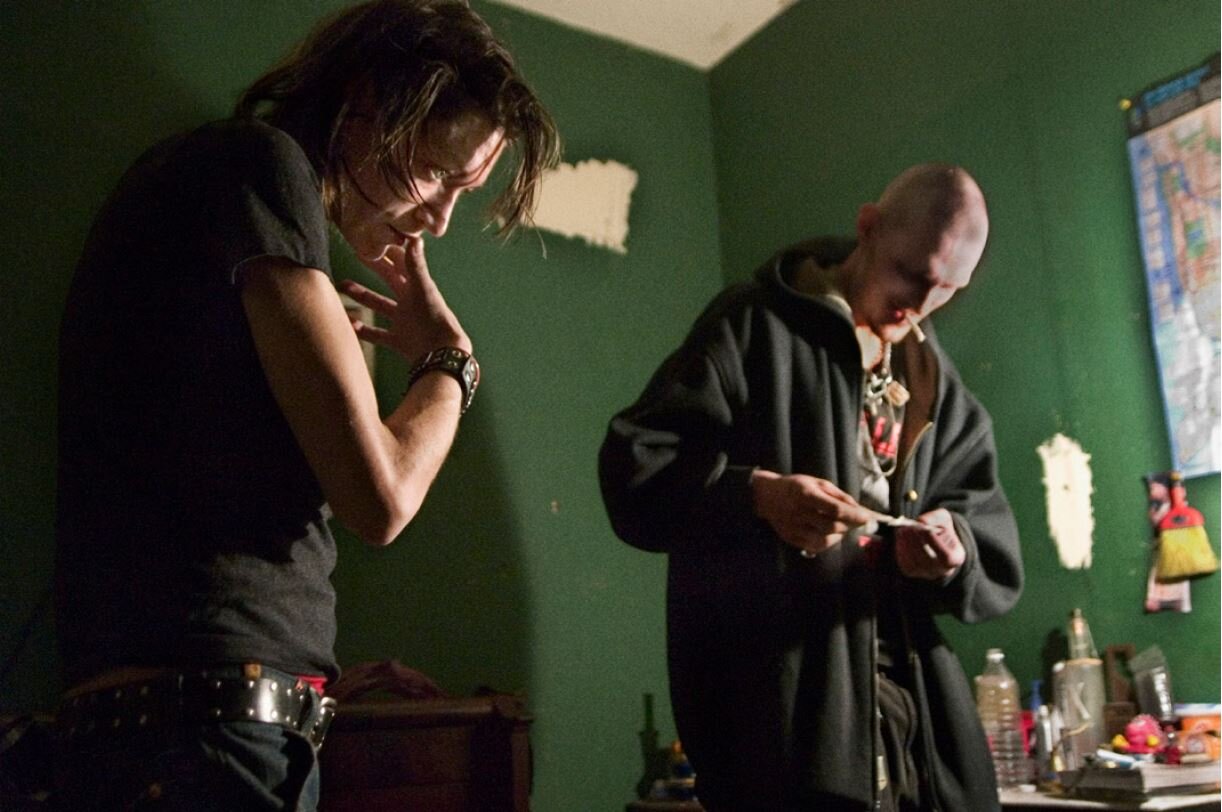

From Our Archives: Addiction - Jessica Dimmock

© Jessica Dimmock

This interview originally appeared in Musée Magazine’s Issue No. 16 - Chaos

JESSICA DIMMOCK: I always had an interest in photography. My dad ran the printing press of the The New York Times, all of my life in my parent’s apartment in NY. He’s a terrible photographer; I don’t even know how we’re from the same gene pool. He’s just horrible at it, but I grew up in this home where we always talked about how the image looked on the page, because that’s what my dad did. He got me a camera when I was young, I set up a dark room in the bathroom in our two-bedroom one- bathroom apartment when I was a kid. I always really loved taking pictures, it just never occurred to me that I could do it. It seemed like something other people got to do. It didn’t occur to me until I’d been teaching in public school for a few years, and I wasn’t picking up my camera at all, and I missed it. It made me feel insecure.

Part of the reason for being a teacher was that I’d have all this free time and I would make these projects, and I didn’t pick up the camera once and it was eating away at me. Then I met this guy in a coffee shop, he’s a great friend to me to this day, who had gone to SPA. I met him while grading papers and he said; “You should go to art school, if this is what you want to do, you can do it.” That shifted everything. ANDREA

BLANCH: Do you set up any of your shots or is it spontaneous?

JESSICA: No, its all spontaneous. Unless its a portrait, but I’m really best with an environmental portrait anyway. I’m really my best when someone has me in their home and then I take a picture of them there. I’m a better observer than anything else.

ANDREA: You mentioned in an interview for PhotoShelter that you stumbled upon your subjects for “The 9th Floor”. How exactly did that happen?

JESSICA: I was studying photography at ICP, and I was walking around with my camera on a way to a friend’s dinner party. A man approached me wanting to know if I was a photo student, and if I wanted to photograph him. He kind of made it clear that other art students had photographed him, and he also made it clear he was a cocaine dealer, and that if I wanted to follow him around I could. So I said yes, and followed him for just three nights, which in the scope of the project is kind of nothing. I went to a bunch of places with him, I went to parties, to apartments where he sold, and telephone booths and stuff like that, and the very last place he ever took me was the apartment where the 9th Floor takes place. He said, “This is Jessica, my photographer”, because I came in with him, they were very open with me that first evening. They were like, “Oh you can take some pictures of us too”. He then was arrested, probably because he was walking up to strangers telling them he was a cocaine dealer, but from that initial connection, I was able to reestablish a little bit of a connection. It took me a while but I was able to find that again.

© Jessica Dimmock

ANDREA: So, after the first night, you left, when you came back the second time, when you rang the buzzer what did you say?

JESSICA: I kind of assumed that Jim, the man from the street, would take me back there again. I’d never thought he would go to jail, I had no idea that would be the scenario. So, I didn’t know how to get in touch with these guys, and I knew that the apartment that I’d seen was something really unique and crazy and special, and I didn’t know how to get back there. So I hovered around Union Square, because I had heard that night in talking to them that they hung out there, and after a month I saw one of them and I was like “I have been looking for you”. I basically said, I have all these pictures that I took that night and I’d love to give them to you, and could I come by tomorrow and give you guys some pictures and they said sure. So, the very first time I came over after that I didn’t even come with a camera, just a stack of prints and they really liked them and that became something that I did pretty regularly; I always brought pictures from the previous time with me, and I found that that really worked to get them kind of excited to see me but also to get us all on the same page. I mean, these are people all doing a lot of very illegal, dangerous activity and its not like that’s not being shown in the pictures, but I think somehow seeing the images through my lens and seeing what I was seeing there, kind of allowed that trusting relationship to build up. Certainly there was a lot of illegal activity in those images, but I think that by me sharing them with them and not keeping it secret and hidden helped.

ANDREA: When Jim brought you up there, what was your initial reaction?

JESSICA: First, it was really shocking, and I knew I needed to just chill out, be calm, and not seem nervous. The other thing that happened dawned on me later; I think I felt it immediately, and I just didn’t know that I felt it. My dad was an addict when I was a kid, and I had been in lots of places like this. I’m pretty sure that I never saw people using in front of me, but I was around that type of adult for sure as a child. I definitely didn’t seek this project out, I just bumped into it, I didn’t want to solve some daddy issues or anything like that. I think in my gut, my immediate feeling of “Oh I know this type of person”. There was something about being very vacant, everyone being there but not being there. People not really connecting with each other. The kind of empty look in people’s eyes, and I think it just struck me as really familiar. Even though it was kind of shocking, I felt more comfortable with that environment than I should’ve been. I mean I was brand new at photography, this is the first thing I’ve ever done.

© Jessica Dimmock

ANDREA: How did you manage to navigate boundaries between being intimate with your subjects and protecting yourself?

JESSICA: I tried to not think about me too much, I tried to be really open. Again, because I hadn’t been doing this for a while, or any time at all, I hadn’t been hardened or I didn’t have any ideas about maintaining distance or maintaining objectivity, which I don’t believe in anyway. I cut my teeth on this project and there was no way to stay truly objective. At the beginning it wasn’t complicated, and in the last year or so of the project it got really complicated for me. I had met these people, Jessie in particular, under the premise of me not judging her. Part of the reason that this woman lets me see her is that I’m going to be someone in her life, probably the only normal sober person in her life, that doesn’t judge her.

When you’ve been using for that long, you don’t really have those people in your life anymore. Then two or three years in, when I really care about this woman it’s impossible not to try to change her, and addiction doesn’t really work that way. People don’t get cured from addiction because their friends plead with them, they don’t get cured from addiction because people around them die; it’s not how it works. There was probably a feeling of betrayal on Jessie’s part. Where she was like, “wow wait, now all of a sudden the terms are different. You said you wouldn’t do this, and now you’re coming down on me too”. When you spend all this time with these people, and you develop a relationship, it’s painful to watch them do things that are really dangerous and painful. People died during the course of that project, I was lucky that none of the people that I had become close with did, but I know of five / six / seven people that died during the course of that project.

ANDREA: Are they in the book?

JESSICA: They’re not really. People have done projects about addiction before. There was no need for another one, and I felt like one of the only things that I could contribute was a sense of intimacy with these particular characters, so because of that I really honed in very closely on just a couple of people. There’s a lot of chaos in the book, but you still kind of follow some folks, but you know there were these peripheral people, definitely people that I photographed a lot, that were dropping left and right.

ANDREA: How did you cope? Did you have people that supported you?

JESSICA: I had a good boyfriend at the time, someone who I am still very close with, but I think I spent a lot of time alone, which I think for me is one of the best ways to process. In more recent years as I’ve tried to maintain a normal life or have a resemblance of social life, coming back into the regular world, after immersing myself in other projects, that toggle back and forth has kind of been the death of me. It’s ruined relationships, it’s made me really feel that I’m not in either world. I think at that time I might just have spent a lot of time alone, which is probably a good thing. I never even thought about it before you asked… I should probably do more of that. It was just heavy, and I think I processed it by not running back to my friends. I also hadn’t been doing it for that long so I didn’t miss people in the same way that I do now. I didn’t crave my normal life, I was newer at it.

© Jessica Dimmock