Japanese Internment: America’s Haunted Past

© Ansel Adams

Loading bus, leaving Manzanar for relocation, Manzanar Relocation Center, California.

On Feb. 19, 1942, Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 which resulted in the relocation and interment of over 110,000 Japanese Americans across the West Coast of the United States. Executive Order 9066 was issued 10 and a half weeks after a surprise attack by the Japanese at Naval Station Pearl Harbor, and used as an attempt to protect against espionage and any possible sabotage on American soil. The attack propelled the U.S. into World War II and prompted a response from the government that stripped the rights of American citizens who were of Japanese descent.

© Dorothea Lange

Oakland, Calif., Mar. 1942. A large sign reading "I am an American" placed in the window of a store, at [401 - 403 Eighth] and Franklin streets, on December 8, the day after Pearl Harbor. The store was closed following orders to persons of Japanese descent to evacuate from certain West Coast areas. The owner, a University of California graduate, will be housed with hundreds of evacuees in War Relocation Authority centers for the duration of the war.

In March of 1942, a civilian organization called the War Relocation Authority (WRA) was created to plan, set up, and execute Executive Order 9066. The WRA’s first lead director, Milton S. Eisenhower, resigned after four months at his post due to the belief that the organization was incarcerating innocent citizens.

Internment camps were located throughout the country, but primarily on the west coast, an area which was home to many Japanese immigrants who began families and took up lives in the U.S. In total, 10 relocation facilities were created across California, Arizona, Colorado, Wyoming, Idaho and Utah, with populations of the camps growing to numbers nearing 20,000. Manzanar, Tule Lake, and Heart Mountain were among the most well-known camps, the former of which were both located in California, while the latter was in Wyoming.

© Dorothea Lange

Japanese-Americans transferring from train to bus at Lone Pine, California, bound for war relocation authority center at Manzanar.

It was through the WRA that photographers like Dorothea Lange and Ansel Adams were hired to document the life of citizens in internment camps. Lange used her film and composition skills to showcase lives that were drastically changed and families attempting to find comfort in the uncomfortable. Raw emotion stood at the forefront of Lange’s work for the WRA. Several images were not publicly shared during WWII and were instead redacted and censored.

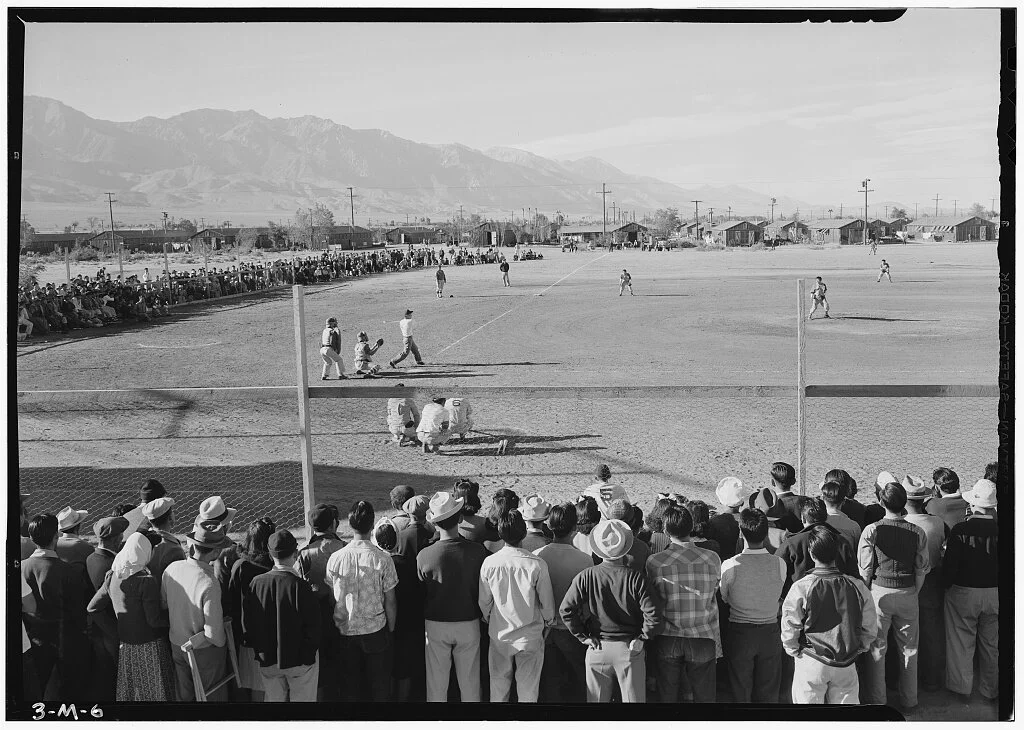

© Ansel Adams

Baseball game, Manzanar Relocation Center, California.

Like Lange, Adams spent his time at Manzanar on assignment, but with a vastly different approach. His offerings provided a look at interned citizens attempting to make the best of their situation. Images of thousands of Japanese Americans watching and playing baseball were meant to show the outside world that those who were imprisoned were just like other Americans. Adams wanted to show not only the American people, but the WRA that interned Japanese citizens were just as ‘American’ as the rest of society.

Though the works of Lange and Adams were powerful, striking images, most were censored during the war. It was the work of interned photographers that conveyed a sense of what life behind the barbed wire, truly was.

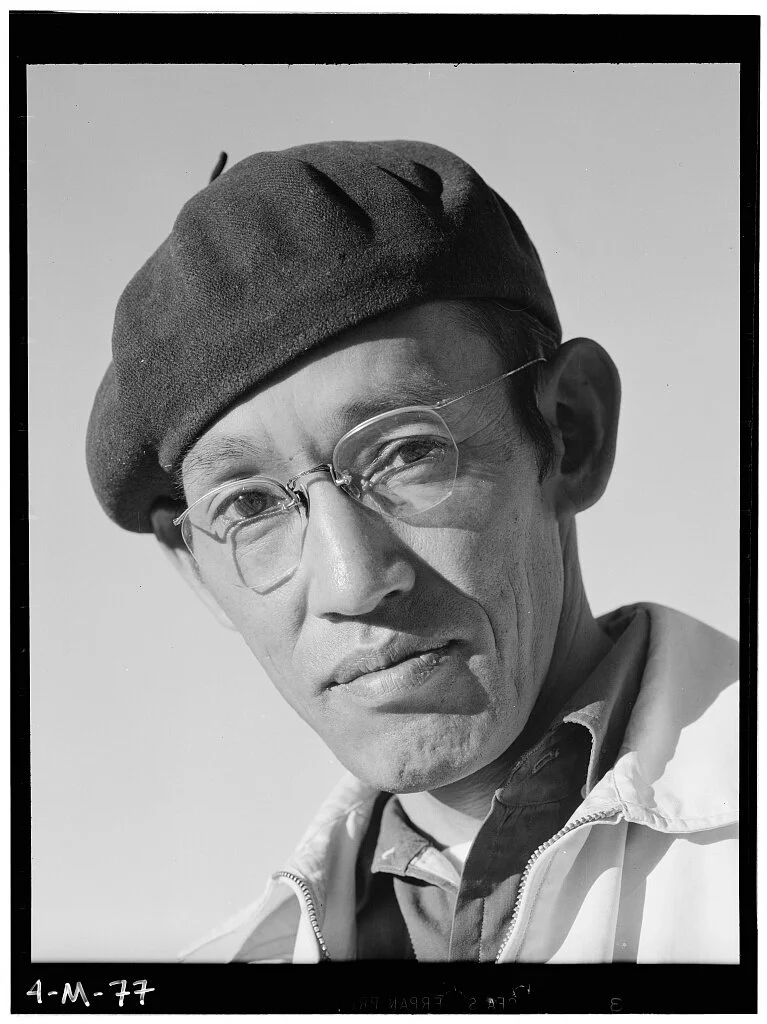

© Ansel Adams

Toyo Miyatake, (Photographer)

Tōyō Miyatake was a photographer born in Japan in 1895, by 1909 he had immigrated to Little Tokyo in Los Angeles to join his father. In 1923 Miyatake bought his studio, which is currently still in operation. It was in 1942, following the attacks on Pearl Harbor and Executive Order 9066, that Miyatake and his family were placed in Manzanar Relocation Center. Those interned were told to bring only what they could carry in two hands, for Miyatake, the priority was smuggling in camera equipment. With only a lens and a film holder, Miyatake began discussing plans with an interned carpenter and a welder to create a discrete home-made camera. With the help of those outside the interment camp, Miyatake acquired film and begin his private documentation. According to Alan Miyatake, grandson and manager of the Tōyō Miyatake Studio, “[Tōyō] felt it was his duty to do this so this would never happen again.” To this day, the camera remains in working condition and in the possession of Miyatake’s name-sake studio.

© Ansel Adams - Inscription reads, “Monument for the Pacification of Spirits”

Monument in cemetery, Manzanar Relocation Center, California.

It was a year after his incarceration that Miyatake approached Manzanar’s project director, Ralph Merritt, to request to serve as the camp’s official photographer. Merritt agreed to the proposition, but due to strict rules, Miyatake was not able to physically take the picture. He was only able to position and frame his photographs, while the shutter of the camera was released by a white assistant. Through his time as the photographer for Manzanar, Miyatake met Ansel Adams and they became frequent and longtime collaborators.

Miyatake used his status as camp photographer to show a retrospective of what lives within the internment camps truly looked like. His most moving images encapsulated the dreams of the interned Japanese American citizens by showing their hopes of cutting the very fences that kept them in.

© Ansel Adams

Farm, farm workers, Mt. Williamson in background, Manzanar Relocation Center, California.

A majority of the interned Japanese, “never talked about their bad experiences” and, “were brought to make the most of their situation,” Alan Miyatake stated. He continued by saying the Miyatake family, “didn’t bring out [Tōyō’s] photo(s) until the 1960-70’s.” In 1978, Miyatake and Adams exhibited and published their works from Manzanar titled, Two Views of Manzanar.

On Dec. 18, 1944, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of Mitsuye Endo, a key witness in Endo v. United States, and stated that the WRA has no authority to subject loyal citizens to relocate. The last of American internment camps closed in March of 1946, and in 1976, President Gerald Ford officially repealed Executive Order 9066. A formal apology was issued by Congress in 1988, and the Civil Liberties Act awarded $20,000 ($43,222 in today’s money) to over 80,000 Japanese Americans as reparations. Though a notable act on the part of the U.S. government, no amount of money will ever reverse or fix the effects and damages of a racially motivated stripping of American citizens basic liberties.

© Ansel Adams

Calesthenics

![© Dorothea LangeOakland, Calif., Mar. 1942. A large sign reading "I am an American" placed in the window of a store, at [401 - 403 Eighth] and Franklin streets, on December 8, the day after Pearl Harbor. The store was closed following orders to pers…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5702ab9d746fb9634796c9f9/1580494995316-S46LK8M9PLHANH8RPCUV/%2522I+am+an+American%2522+placed+in+the+window+of+a+store%2C+on+December+8+%28Lange%29.jpg)