Lothar Baumgarten at Marian Goodman: "The Early Years"

Tetrahedron (Pyramid), 1968. Lothar Baumgarten. Stacked Pigment. Courtesy of Marian Goodman Gallery.

LOTHAR BAUMGARTEN: The Early Years

By ClydaJane Dansdill

Marian Goodman Gallery, which sits up and away from bustling midtown near by the eastern corner of Central Park, one enters the familiar calm of a gallery space that feels especially veritable in its stillness. The drafty rustle from the gallerist’s desk mixes with faint sounds from "Origin of the Night" (Amazon Cosmos), 1973-1977 playing down the hall, a 102 minute video installation shot on 16 millimeter film that I would later find myself transfixed with for the entirety of its roll. Something delicate and dark flitted past my head before I had reached the first framed photograph. A butterfly glanced off the window and drifted down to rest on the ledge. Another fluttered over my shoulder, landed for an instant in the palm of my hand, and then floated up to the white washed ceiling. These butterflies were housed in a glass terrarium fitted with a variety of kale native to Baumgarten’s home region of Rheinsberg. The box is lit cleanly with white neon and bestirred by half a dozen monarchs. The sculpture, Conservatories (Guyana) (1968), which preoccupied me completely, is a tribute and reference to the region of Guyana, a stretch of undisturbed rainforest at the edge of the Amazon Basin. The intent of this piece is to deflate the breadth of alienation between the Western World and non-European cultures by presenting a tiny arboretum whose contents connotate two symbols of space and place. The miniature hothouse is delicate yet fortresslike. The verisimilitude for the natural world that Lothar Baumgarten possessed gleams, substantiated, in the corner of the gallery.

VW do Brazil, 1973-74. Lothar Baumgarten. Chromogenic print. Courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery.

Conquista Rochade, 1971. Lothar Baumgarten. Chromogenic print. Courtesy of Marian Goodman Gallery.

Pupille (eyeball), 1968. Lothar Baumgarten. Chromogenic Print. Courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery.

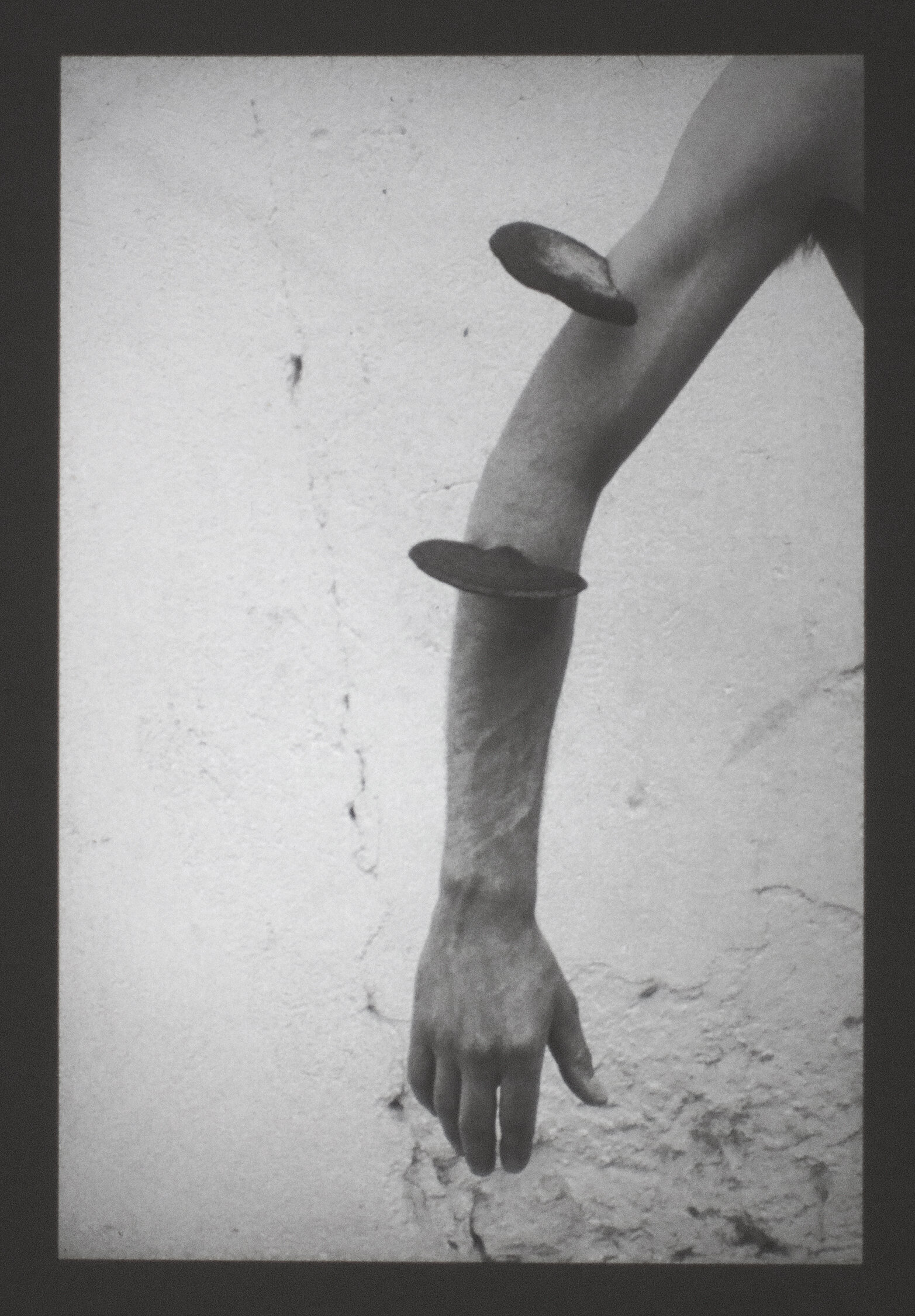

Distracted by the butterflies and drawn with delight to Baumgarten’s striking azure pigment pyramid, Tetrahedron (1968), I finally made my way through the photographs. Lothar became interested in photography as a child. At the age of five, he was having trouble expressing himself to his father, and said “I’d like to give you a picture from what I see.” His father, who worked as an ethnographer, gave him an Afga box camera. On view at Marian Goodman are selections from Baumgarten’s 1968-72 color series Culture-Nature (Manipulated Reality). A giant palm frond in the back seat of a vintage Volks Wagon, a gaggle of toads on a chess board, Baumgarten’s signature red tetrahedron in the woods among the leaves, a blue rubber ball tossed upon a tattered lily pad - each of these images evoke an ephemeral crossing of a civilized world with wilderness, all recorded along the banks and back woodlands of the Rhine. His black and white pictures, placed adjacent to the color prints ring with a similarly surrealist, sublimative tone of marrying nature with humanity. Feuerschwamm (Polyporus fomentarius) 1968, which features a human arm adorned with shelf mushrooms, strikes the viewer initially as some kind of human malformation before image is realized and the clever wit of the concept solidifies. Each of these pictures provide an enigmatic world, or perhaps circumstance, that involve a kind of intervention between civilized ephemera and natural beauty. Feathers bristling out of a mound of dirt, or the enigmatical symbolism of a hair pin and a toy alligator in a bathroom sink.

Caiman, 1970. Lothar Baumgarten. Gelatin Silver Print. Courtesy of Marian Goodman Gallery.

Feuerschwamm (Polyporus fomentarius), 1968. Lothar Baumgarten. Gelatin Silver Print. Courtesy of Marian Goodman Gallery.

The exhibition also included drawings, maps, and a 1968-1971 photographic essay and 1961 slide projection Unsettled Objects. The range of eighty-one pictures clack one after another in the dark South Gallery, one colored shot appears to breathe in its contrast to the next, scientific verbs and adverbs from Baumgarten’s first text piece offer a knowing nod to the institutional end of natural history and ethnography. In Marian Goodman’s press release for The Early Years, Baumgarten is quoted as follows: The slide projection drafts “an aesthetic alphabet of the interaction between language and form...and maintains the contradiction between culture and nature, and mirrors in its ambivalence our representation and cultural vision of nature.”

Pigment geschichtet (Pigment stacked), 1968. Lothar Baumgarten. Chromogenic print. Courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery.

The film Origin of The Night (Amazon Cosmos), which I came across last, is an incredible, almost surreal examination of the sounds and sights of a very closely monitored rainforest floor. It is revealed later, however, that the footage was actually taken along the banks of the Rhine in Germany. This magnetic, blithe montage is a commentary on humanity’s distance from nature, and Baumgarten is able to single handedly flip Westernized misperceptions of tropical forests on their imperious heads. In addition to the wit of the film being not what it seems, its aftermath is still enchanting, and endows the viewer with a renewed perception of the vastness and scale of the world’s wilderness. It acts as a kind of closure to Lothar Baumgarten’s truly incredible show of photographs, each of which stands as a totem for his life, vision, and work.