Above Image: Garry Winogrand (American, 1928–1984), Centennial Ball, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1969, Gelatin silver print, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Gift of Dr. L.F. Peede, Jr., © The Estate of Garry Winogrand, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

Garry Winogrand was American as Hell. He returned from the war with the optimism that comes with peacetime. Garry's process was to run around with a handheld snapping shots with tilts and a style that at first glance seems anarchic.

Garry claimed never to compose, never to think, just do. This frames him as a photographic beat, taking a stream of consciousness approach and focusing on the country he traveled through, his city, and what he found interesting.

Garry's road trip through America left him sour. Continuing the beat tradition.

He wrote in his first Guggenheim Fellowship some rare insights into what he felt when taking his pictures.

“I look at the pictures I've done up to now and they make me feel that who we are, and how we feel, and what is to become of us just doesn’t matter. Our aspirations and success have been cheap and petty. I read the newspapers; I look at some magazines (our press). They all deal in illusions and fantasies. I can only conclude that we have lost ourselves, and that the bomb may finish the job permanently, and it just doesn’t matter, we have not loved life. I cannot accept my conclusions, and so I must continue this photographic investigation further and deeper.”

This pessimism, bordering on fatalism only increased the longer he produced work, looking in vain for something to disprove his conclusions.

It is vital that we keep up with Garry's voice. Keep up with Garry. That's almost impossible. Well you have to try because he claimed to be experimenting, and experimenting implies a thesis. He had a thesis? You just have to start digging and find it under the layers of self-effacing mantras.

“If the photograph isn't more dramatic than the event itself, then it is worthless.”

But do you go into the world looking for that?

“Of course not, I don't know what's going to happen”

He just wanted to get out there. You have to submit to, not control, photography.

Garry Winogrand (American, 1928–1984), Centennial Ball, Metropolitan Museum of Art,, New York, 1969, Gelatin silver print, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Gift of Dr. L.F. Peede, Jr., © The Estate of Garry Winogrand, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

If Garry is a beat, he is Kerouac. It's not writing, it's typing. But Garry had talent. Okay, he had talent! But he was more Kerouac than Burroughs, notoriously bad at editing his work, routinely turning in 200 images during his journalism days when only 5 or 6 were required.

Art is light years ahead of writing. Art has deconstructed itself, free to experiment, free to do anything, and it was with this freedom that Garry left the scribblers behind.

Knowing Garry’s journalism background is essential to understanding his work. He was a working man. Proud working man. Salt of the damn earth. Exactly, Salt Of The Damn Earth.

His patron Szarkowski would say, “Form and content are inseparable, and you cannot say the same thing in two ways, no image could really symbolize anything beyond itself.”

What do symbols mean? Virtually nothing, and because they mean virtually nothing they can be argued about forever. All arguments stem from confusion, and all arguments are a waste of time unless your purpose is to cause confusion and waste time.

It's impossible to view something on a purely aesthetic level; we need something to anchor us to these images. We need something to help us know what is going on. What about social commentary?

That's all the viewer. All images are lines and colors.

It's lines and colors on the faces of a changing country and you're full of shit if that does not evoke something.

Lines and colors don't evoke anything.

The actual exhibit progresses chronologically. Garry did his best to keep himself out of the picture, but it is impossible not to see the decline of America. Still don't see any reason not to accept his original conclusions.

He begins in the late ‘50s back from the war, excitedly photographing people on the streets of New York. The country was powering forward with amazing speed and his frequent pictures of cars, trains and automobiles showed the larger optimistic view towards the future.

Then the ‘60s came, all idealism and youth. Garry touted his camera around central New York City. Anti-War rallies, the Beatles arrival, the Democratic Convention. He is always on the peripheries. His focus was never anything other than those small everyday moments that are constantly missed while other photographers are leaning fitfully forward, craning over their comrades to get a shot of JFK.

As the ‘60s progress the idealism vanishes in a sea of police brutality, the mire of Vietnam, the Cuban Missile Crisis, and finally the death of a president. Always interested in politics, Garry would go out of his way to memorize minor figure’s schedules and show up and get some shots, but that was his journalism training. After the Cuban Missile Crisis, he disdained all politicians, and after the death of JFK, never spoke of, or showed, a political figure in a positive light. His Democratic National Convention images were snaps of RFK between the shoulders of the more blessed press in the front row. Those were the front row political saps. Garry was salt of the damn earth.

Garry Winogrand (American, 1928–1984), Los Angeles, California, 1969, Gelatin silver print, Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco, © The Estate of Garry Winogrand, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

Then came his second Guggenheim fellowship, where he traveled to Texas and LA.

Texas in the late ‘60s, early ‘70s was a magic foreign land full of bouffant and ten gallon hats. Garry acted like an American; he was a tourist. Bloated balloons of swollen chested cowboys, oil money walking past with massive belts. He would revisit Texas several times during his career. The country was smaller than it used to be. It was accessible; Texas was no longer the isolated racist wonderland that killed presidents. It was a place of oil money and kept women. It was a place of insane, screaming, cattle auctions and rodeos.

From Texas one photo stands out: a rodeo clown in dripping, absurd, makeup runs from a 1600lb bull.

The clown had jumped into the arena and the bull turned. The bull paused and looked from the fleeing cowboy whose hat had fallen and was lying in the dust. The sunlight lit the arena on the side away from the clown. The clown already had one foot up and his eyes were dead behind the blue paint, his mouth was taught under his red grin. It was a good bull. The bull would run and try to gore him. The bull shivered and its shoulder muscles would twitch before it took off. The clown was looking behind, waiting for that twitch. The clown was a good clown, so he ran. The bull would follow while the cowboy scrambled up the wall, forgotten by both crowd and bull.

From Texas, Garry followed the country to the suburbs. No more urban photography. He went to LA. LA isn't a city. “Hah, anyone who says LA is urban, don't really know how the place works.” Does the place even work? Garry's pictures from LA show an empty country, waiting to be filled. Manifest destiny? No, no more optimism for that.

He died in LA. He died mostly because he smoked 3 packs a day and worked like a madman. Salt of the damn earth. American as hell. He left 600 rolls of undeveloped film. No editing. That's not writing, it's typing.

The last pictures, from his last travels. Back to New York, back to Texas; show the ‘80s. No one needs reminding how miserable the ‘80s were.

The exhibition showed the evolution, the devolution, the fall of American idealism and the rise of American ego. Garry’s pictures in his late work flow from his pessimistic pragmatic view of the world and begin to border on fatalism.

Of course we don't know what pictures he would have chosen.

He would have chosen the good ones. He would have gotten someone else to choose the good ones. Well he did. He got the Met to do it.

They did a pretty good job. The show is America. Better things to do on 4th of July than look at fireworks. Go look at America and see the same street scenes with old fashions and forgotten homeless veterans that you see every day. Well, Winogrand never wanted to reform life, just show it.

Text by John Hutt

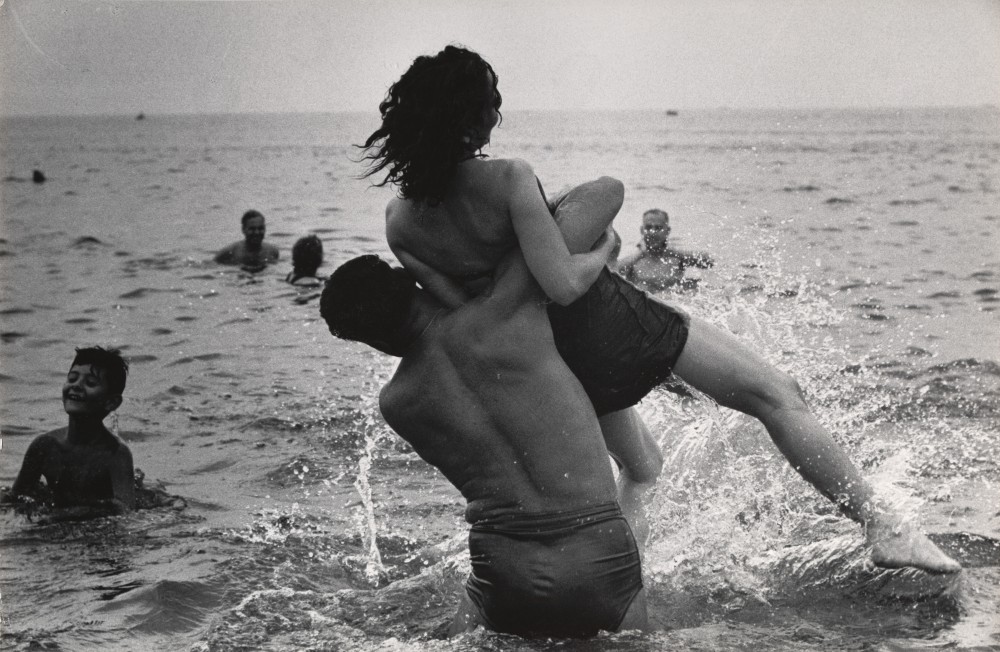

Garry Winogrand (American, 1928-1984), Coney Island, New York, ca. 1952, Gelatin silver print, The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Purchase and gift of Barbara Schwartz in memory of Eugene M. Schwartz, © The Estate of Garry Winogrand, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco