Steve Miller

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Steve Miller was born in Buffalo, NY, educated at Middlebury College and moved to New York in the late seventies. He teaches as part of the senior critique at the School of Visual Arts.

Over the past 31 years, Steve Miller has presented 33 solo exhibitions at major institutions in the United States, China, France, and Germany. His exhibitions have been reviewed in Le Monde, Süddeutsche Zeitung, The New York Times, The Boston Globe, ArtForum, ARTnews, Art in America and Isto E. Miller was one of the first artists to experiment with computers in the early 1980’s, and his work today continues to integrate science, technology and fashion with fine art. Using the lens of technology Miller reinvents at the traditional painted portrait, the world of fashion, particle physics, molecular biology and the world environmental crisis. In 2007 Miller exhibited a collaborative project on the subject of human protein with the 2003 Nobel Laureate in Chemistry, Rod MacKinnon, in a solo show at the Rose Art Museum at Brandeis University. In 2013 this project will be a solo exhibition at the National Academy of Sciences in Washington, DC curated by Marvin Heiferman.

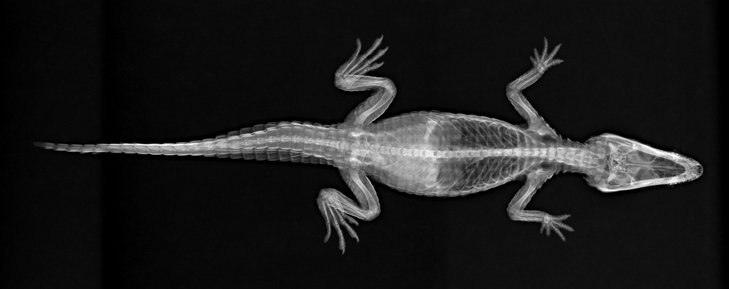

His current project, entitled "Health of the Planet," is about the rainforest in Brazil. The forests of the Amazon are the lungs of our planet in that they process the oxygen/ CO2 exchange essential for a healthy global environment. This project gives Brazil a medical check-up with an examination of our global lungs by taking x-rays of the plants and animals of the Amazon.

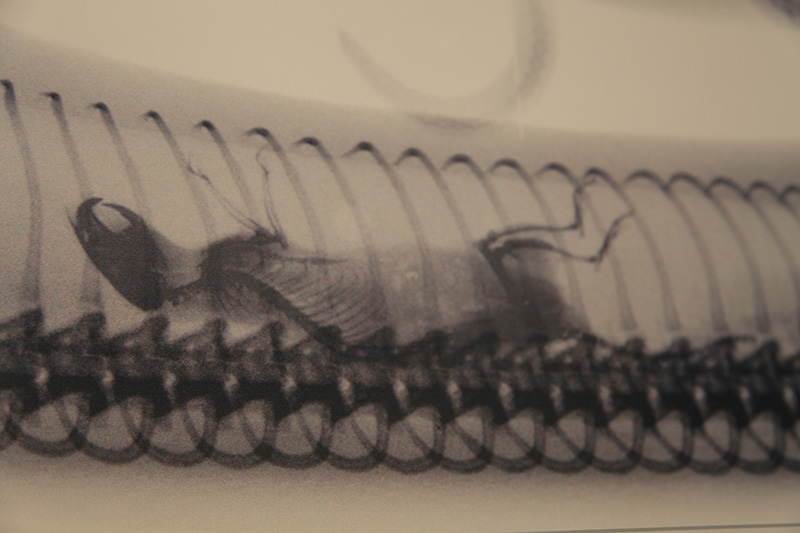

In August 2011, Miller worked with the Instituto Goeldi in Belem to create a series of x-ray images revealing the extraordinary beauty of Brazil’s biodiversity. This work is an extension of his project “Saude do Planeta” which began with x-ray images of Amazon plants in 2007. For an exhibition in Rio last November Miller used the title "Fashion Animal". In this exhibition The simple clarity of these new animal images in black and white were hung next to a series of brilliant colored x-ray prints of hand bags, shoes and jewelry. This marriage of the organic to the technical asks the viewer to diagnose both their own state and that of the earth.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Photographs by Michael Pina

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

This is a project called “Health of the Planet”. I’m working with scientists in Brazil and the idea is: if the Amazon is the lungs of our planet, I am submitting Brazil to a medical check-up by x-raying the lungs. I’ve trademarked the name “Health of the Planet” in the US and Brazil. My current show is in East Hampton at Harper’s Books, which runs from July 13th until August 13th. The show includes glass sculptures, paintings, unique artist’s books and print editions. The project involves looking at the natural resources of Brazil – in this case, the flora and the fauna. I am also remote-sensing images, satellite images, and I’m working with scientists: vets, botanists, the zoo, and radiologists. The plants were done in São Paulo in 2007 because you need a hospital to do the project. You need the equipment close to the plants. The advantage of São Paulo is they have an enormous flower market. I started with a botanist, I went to the flower market, and I picked out all of the Amazonian plants, and took them to the hospital. The second phase was going to Belém in 2011 and working with the zoo and the radiologist, which took three years to do. One of the formats in which I’m showing this work is in unique books. So, it’s sort of this dialogue between natural resources and the need for these resources. Rio, and Brazil in general, are famous for their favelas: huge and unregulated housing that is chaotic. One image of this chaotic need for resources is the electrical wiring system of the favelas. I mean, you see this stuff in every developing country. People say “oh, I’ve seen that in India, I’ve seen that in Central America”. The first time I went into the favela, it was run by the drug-traffickers. You had to go in with a bodyguard, make a donation to the local hospital, and they know that you made that donation and then they tell you when you can photograph. I take all of the photographs, and then some are silk-screened onto other pages that are digitally printed.

How did you print them?

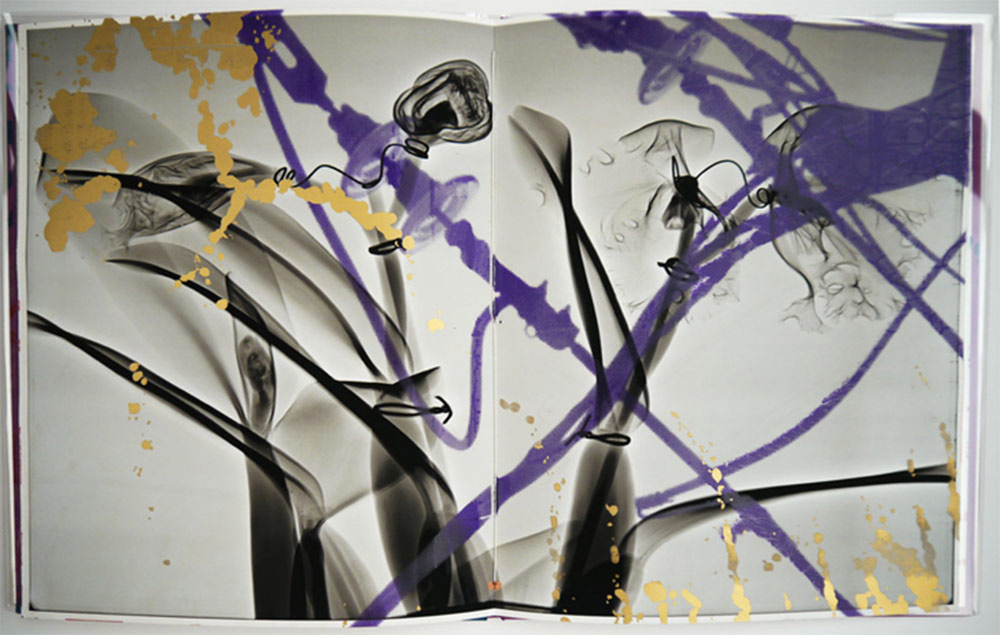

For example, this is a digital x-ray of a Brazilian plant and then I silk-screened on top a satellite image of the Amazon River basin.

"Flora Favela" 2011, unique book, digital carbon print and silkscreen.

It takes a year to print a book. I have to wait a day for the enamel to dry, and then 360 pages in this book. So I figured that the best way to show these books was to make a sculpture – making the sculpture instead of a book. What happens with art is that you stop looking at it for a while. In this case, you can just switch it up and find a page you like. You have the ability to keep flipping through the book and play with the different compositions. You can have a black and white experience or you can do something really colorful. It’s so much fun to look at these things.

How much are they?

The print editions are $2,600 each, with 12 examples in each edition. Unique books are $5,000 to $7,000 and the book sculptures are even more expensive.

Tell me about the sloths.

The Sloths are like the canary in the coal mine because they’re very sensitive to lung pollution. They’re having a lot of lung problems, according to the vet in Belém. Their tree habitat is being destroyed. This is an animal that is really stressed out.

Does Philippe Laumont print these?

I love working with Philippe and he has printed some great editions for me, some of which are available on ArtSpace.com. However, these are printed by a friend that tricked out a digital printer with off-market carbon. The problem with the carbon is that it clogs the nozzles during the printing process, which causes you to lose pieces. But, it gives you an amazing tone.

The project started because I went to the Amazon rainforest on the first trip with Nessia Pope. We went to this island called Ilha Grande that has trees with these fruit thirty feet up in the air, and if they fell, they would knock you out. I asked myself, “What’s inside of these things?” A year later, I went to the market in São Paulo. There was one building the size of a football field, with nothing but this fruit called jaca that usually grow only one a stem. I went through piles and piles and found two fruit on one stem. They looked like lungs which was the perfect metaphor for “Health of the Planet.”

Sometimes I take other people’s books. This one was originally a book by Ralph Gibson called Brazil, and I asked him if I could do an intervention on his book. I printed the title again, found the font, silk-screened it, so instead of “Brazil by Ralph Gibson”, it’s “Brazil Brazil by Ralph Gibson/Steve Miller.” His original title page was the word “Brazil” in red and “Ralph Gibson” in black. I then screened my name and silk-screen the x-ray orchid image on top, and in this case, we co-signed them. There are twenty editions of these with printing on top of them. I traveled with Ralph in Brazil and witnessed his process, which was fun.

For this sculpture, there is glass behind which the book sits like a pedestal. This much of the glass will sit in the steel and I did a lot of the telephone lines as mirrors, which will be above the book. A lot of the lines in the book are also printed in silver. This is one of the sculptures in the exhibition at Harper's Books. Some of the sculptures are just glass. For example, this is a live alligator that was sedated, tied up with rope – that I removed in Photoshop so it looked natural – and this leans against a wall. In Brazil, I’m also going to make a surfboard with this image for Osklen.

How do you decide on the different techniques of your work?

There are so many variables in that. For the “Health of the Planet” series for example, I start with a digital x-ray file, and then load that digital file into Photoshop because I need to enhance the image in order to get the clarity that I’m looking for. My initial idea was to have a print edition, but the prints screwed up, so I decided not to throw them out, and instead I painted them it, changed the medium, and silk-screened on top.

I don’t choose the technique, it’s more of a necessary result of a need.

Do you prefer collaborating or do you like working on your own projects?

I love collaborating. With collaborating you get everyone’s energy, especially with scientists because they usually don’t get to play. They have this really expensive equipment, there’s a particular goal they have to achieve, and then I come in and say, “Well, can’t we just do this, can’t we just do that?” That’s stuff they’ve always wanted to do, but they don’t get the permission to do it. Also, everyone brings their ideas to the table. One of my assistants, Fabricio Branco, was a student at SVA who was mature and forty years old, and he would come up with some of the ideas, in terms of composition, handling animals, doing anything. Collaboration is about being open to new ideas to which I respond, “Let’s do it!”

What does being an artist mean to you?

Freedom. Doing whatever the hell you want to do. The best thing is being able to play, to pursue any line of thought. The idea in materials is that they lead you different places and you see something happen. The glass thing happened partially because I was asked to do a container to hold plants for a garden in the summer. I was asked to be responsible for maintaining the plants in the container and I thought there was no way I could do that. I tried to team up with someone who knew about plants and was also a trustee of this garden, a well-known designer named Edwina von Gal. She didn’t have the time to do maintenance either and suggested we use moss instead and put it in a glass bowl. The flower, that I originally didn’t want to maintain, ended up being an x-ray on glass in a sheet of steel. Thus, a flower in a container.

Is there any project that you’ve done that you wish you could redo?

Yes. I did a project in Brookhaven National Labs and it was a project involving particle physics. What they were doing was they were taking protons, accelerating them at the speed of light in a ring that was two-and-a-half miles in circumference. This was around 2000 and the most advanced thinking about smashing atoms was that protons held quarks and gluons. When protons collide they make a plasma state called quark-gluon plasma, which was the state of matter at Big Bang. Now the most expensive science experiment is going on in CERN, Switzerland and they are discovering new information about particle physics. This makes me want to reconsider my previous body of work about the Standard Model. In February, I was invited to give a lecture at CERN. I spent three days interviewing the Theory Group, who write the equations, and I photographed the detectors. Right now they’re looking for this thing maybe called the “God” particle, but actually called the Higgs Boson, which is a particle that helps explain mass. It’s really wild because it’s so theoretical and totally mirrors the abstract reality of nature. Somehow art is going to be in parallel to this incredible theoretical mystery of complexity and beauty, it’s all going to come together.

What’s one word that describes your work?

I think I’d like it to be “playful and fun”, but also “non-hierarchal”. I create different bodies of work, it’s not so much about style anymore, so I like that. A lot of people associate me with x-rays, but I’ve worked with other techniques, such as x-ray crystallography. I like the diversity. Usually it’s the idea that generates what it’s going to like.

Where do you get your ideas from? How does it happen?

I’ve always thought that if you’re going to make art out of something, it’s going to be a visual vocabulary and the most exciting visual vocabulary is that of your time. We have these incredible vocabularies right now of technology, of science, of the Internet, of particle physics, of electron microscopes, and that’s a language that is incredibly beautiful. That part of the beauty I’ll talk to because the beauties are already there, you can’t do better than that. That same kind of beauty is embedded in science, and I’m hoping maybe if this project is successful, people will might actually see the beauty of math.

What advice do you have for emerging artists and photographers?

Emerging artists and photographers: those are two different things, or they’re same thing. What I tell my students, assistants or people who work for me, who go on into the art world, is build a network. The reason we go to graduate school is not because we, as teachers, are going to tell you anything that is particularly interesting or give you some knowledge. Everything is about relationships in terms of the students, it’s great if you can have a relationship with a faculty member, but it’s great to have a relationship with the other artists that are in the program, and what happened at SVA is that the best students will all get together after they graduate to build their network of support.

How does your work differ when you’re in love and when you’re not in love?

It doesn’t. I consistently work no matter what. I work all the time because I love it, it’s a complete pleasure to do this. The more I do this, the more excited I get about it. The idea of working all the time is my idea of fun.

If you had to change anything in your career, what might that have been?

Well, early on in my career, I told a lot of people what I was thinking. This is complicated because, I think, you do have to be direct, and you do have to tell people what is on your mind, but you can go over the line, and I’ve gone over the line more than once. Gone over the line to aggressive, gone over the line to insulting, and I rethink that a little bit more. I think I’m a little bit more sensitive to how people feel than my own unbridled ego.

What does art mean to you?

When I’m not working, I’m grumpy, that’s why I work all the time. I think art is this unnecessary activity that we get to do and because it’s unnecessary, this gives you your freedom that makes it completely necessary. Yet, because it has no practical use value, art has its value. In this world based on need, we have this thing that is based on a different kind of need, spiritual, perhaps. It allows you to think things in a different kind of way. Art is about this ability to play and have fun, and it’s also a dialogue between you and the culture.

What’s your definition of an emerging artist?

There’s so many definitions of “emerging”, I mean I’m still emerging. Maybe it’s “what’s an emerged artist?” An example of what is not, would be Gerhard Richter. No one is going to question the fact that he’s emerged. He’s established, he has a wide audience, he’s widely collected, he’s widely thought about, he’s widely influential, and then you step back from him. The traditional emerging artist is like the person who is out of school, that’s been working five to ten years, and they start getting solo shows in galleries. That’s one definition. And then there’s this whole other thing about people who have been working for a long period of time that do really quality work who haven’t quite received the commensurate level of recognition. Everybody knows that they’re good and that they’re artists, but they haven’t really been collected. Is emerging financial? Is emerging about age? Is emerging about the amount of time you put in before you get your due? I think it’s not a simple question.

What’s your favorite food?

Fruit.

Which one?

I love all fruit. Blueberries. Peaches. Anything in season.

Is there anything in life that you want to do outside of your art?

To travel, there’s so many places to see. I’ve never been to the Prado. I’ve been to the Hermitage. Those are just two places you have to go as an artist before you die. My two favorite artists are Titian and Velazquez. I think I need to get to the Prado to see those great Velazquez paintings right away.