A Long Arc: Photography and the American South since 1845

Gordon Parks (American, 1912–2006), Ondria Tanner and Her Grandmother

Window-Shopping, Mobile, Alabama, 1956, printed 2012, inkjet print, High

Museum of Art, Atlanta, gift of The Gordon Parks Foundation, 2014.386.8. Courtesy

of and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation.

Written by Makenna Karas

Photo Edited by Joe Cuccio

History is rarely fixed. More often, it is a palimpsest, graffitied with revisions. But photos, collections of pixels plucked from mid-air, are frozen. They serve as records, filling in the holes of history, offering up portals into worlds you may have never known. The High Museum of Art brilliantly explores these portals in their recent exhibition, “A Long Arc: Photography and the American South since 1845”, using photos to interrogate the roots of American identity in a showing that will run through the 14th of January, 2024, in Atlanta, Georgia.

Spanning from the American Civil War through the civil rights era, the collection unearths and displays moments from history that poured the foundation for America. Photos such as, “2nd Regiment, United States Colored Light Artillery, Battery A: Ram, ca. 1864” serve as a record of that history, documenting soldiers as they carried not just the weight of weaponry, but of war and its morbid reality.

Unidentified Photographer, 2nd Regiment, United States Colored Light Artillery,

Battery A: Ram, ca. 1864, albumen silver print, High Museum of Art, Atlanta,

purchase with funds from the Lucinda Weil Bunnen Fund and the Donald and

Marilyn Keough Family, 2021.275.

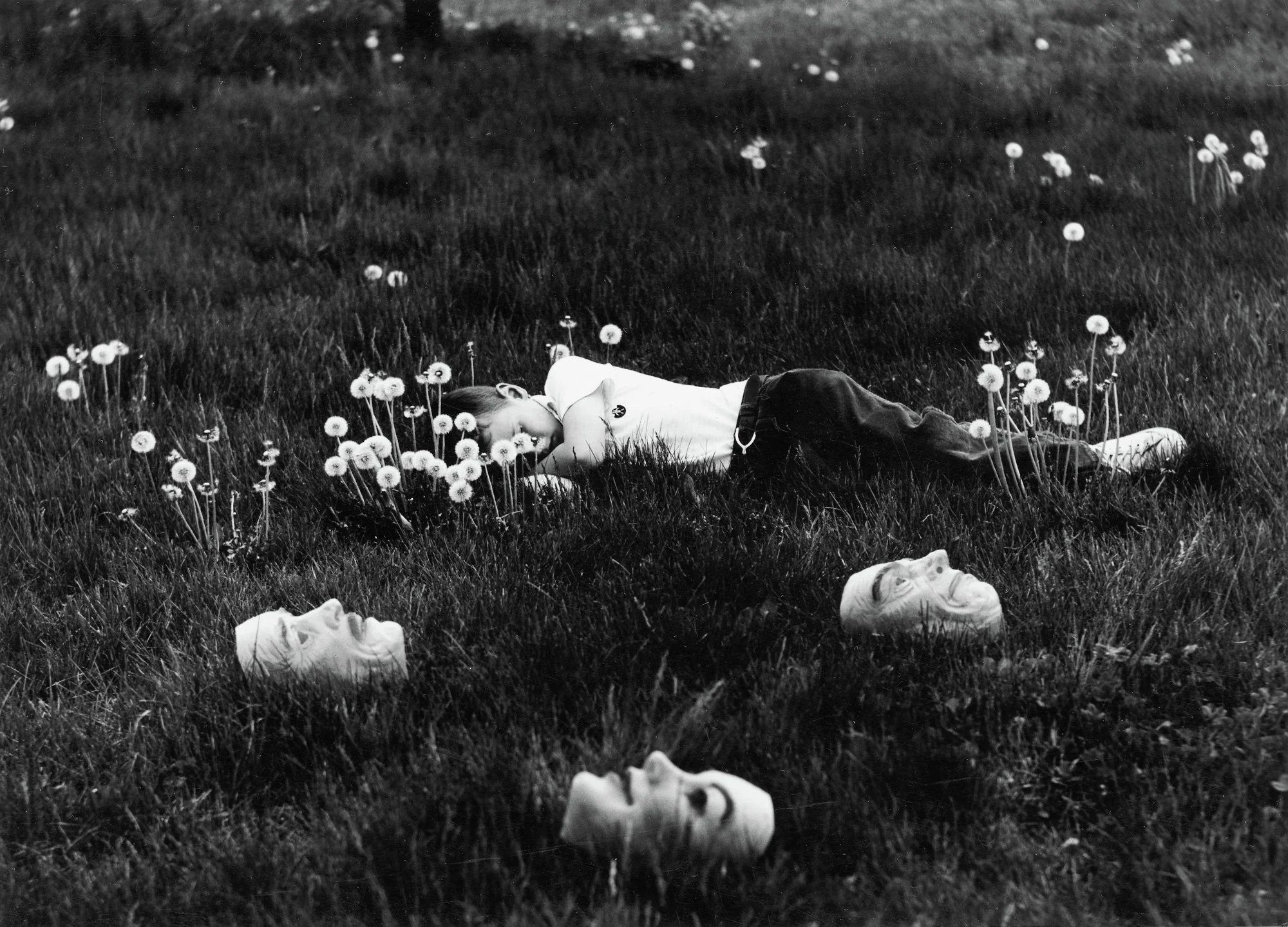

The collection beautifully catalogs how that morbidity persists throughout time, still lingering heavily in the air a century later as Ralph Eugene Meatyard captures his son in “Untitled, 1963”, lying in a field of faces in Kentucky. The child, an icon of futurity, has fallen from innocence, away from the whimsical white flowers above him, away from the myopia of youthful ignorance. Surrounded by disembodied faces, the audience witnesses him coming to terms with the bloodied, haunted history that saturates Southern soil. The stark contrast of black and white beautifully encapsulates an overarching theme, where the past and present are inextricably interwoven, running alongside each other, hand in hand, never able to let go.

Ralph Eugene Meatyard (American, 1925–1972), Untitled, 1963, printed ca. 1963,

gelatin silver print, High Museum of Art, Atlanta, gift in honor of Edward Anthony

Hill, 2018.69. © Estate of the artist.

The series also allocates space for a diverse array of stories otherwise gone untold by the dominant discourse. In “Workers assemble in front of Clayborn Temple for a solidarity march, Memphis, Tennessee, 1968”, Ernest C. Withers documents a strike that Black sanitation workers organized in response to lethal working conditions. The photo acts as a record of their existence and of their struggle, echoing the declaration of humanity that they proclaimed with their signs. The shot is drenched in brutal honesty, working to confront the messy past of a country that has swept far too much under the rug. It pulls the tattered curtains of concealment back, revealing what really transpired in the South and how it continues to inform modernity.

Ernest Withers (American, 1922-2007), Sanitation Workers Strike, Memphis, Tennessee, March 28, 1968), 1968, gelatin silver print, High Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase with funds from the Director's Circle, 2002.24.1. © Dr. Ernest C. Withers, Sr.

For, if there is one dominant theme to the series, it is one of visibility. Each shot, whether of a battlefield in Nashville or an organized strike in Memphis, asks the viewer to look deeply into the eyes of history in order to expand their own understanding of the present. This is poignantly demonstrated in RaMell Ross’s “iHome, 2013”, where you see a Black hand holding up an iPhone camera to an old Antebellum estate. Ross, much like the child in the field of faces, is visiting the past while carrying the future, exploring the threads that bind one to the other in order to offer a new stitch. Existing as a microcosm of the collection, the photo proposes a contemporary way of seeing an old world, one that grasps at, not ignores, the past in order to better understand today. The series, in its stunning entirety, invites us all to do the same.

RaMell Ross (American, born 1982), iHome, 2013, pigmented inkjet print, High

Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase with funds from the Marilyn and Donald Keough

Family Foundation, 2022.159. © RaMell Ross.