From Our Archives: Portraits of Power - Platon

This interview originally appeared in Musée Magazine’s Issue No. 19 - Power

ANDREA: So of all the leaders that you’ve photographed, who would you say had that?

PLATON: Not many. I believe Obama had empathy, but I think his fatal flaw was that he did not con- tinue to communicate with people on a regular basis, and he did not help people articulate what they were experiencing, and that’s part of what a leader in history has to do. To be able to explain, this is where we are, this is why we’re struggling, and this is our collective goal. I thought Aung San Suu Kyi had compassion. When I first photographed her, I was actually risking my life.

ANDREA: How?

PLATON: Well, I photographed her the day she was released from house arrest by the military. And that was a crucial moment in history, like Mandela stepping to freedom. I smuggled myself into Burma and went in with a tourist Visa. I pretended I was a student, hid my camera equipment in my backpack, and went straight to the NLD offices where she was hiding that day after her release. I negotiated a sitting with her gatekeeper, and then I did the picture. And I thought she had incredible grace and compassion. I actually asked her, is love the most important thing? And she said no. Because love is based on passion. It peaks, but it also can turn quickly into hate and rage. And because we live in extraordinarily challenging times, what we need to focus on is something much more sustainable, and that’s friendship and kindness. And sometimes it’s not my picture that judges a leader. It’s history and their legacy, and a picture can mean different things to different times. And time is a fickle ally. Sometimes it’s on our side, but sometimes it can turn on us. If I get a picture right, that picture can represent many ways of looking at someone’s legacy. My picture of Putin, he really loves. But revolutionary groups have used that same picture against him.

ANDREA: What is it that attracts you to power?

PLATON: The illusion of it, and finding out what’s behind that. That was the beginning of my fascina- tion, but I’ve also become fascinated by the responsibility that comes with power. And because now I’ve seen from the front line how bad decisions can affect people. A photographer friend of mine, Tim Hetherington, was actually killed in Libya.

And we would always chat about stuff like this. I would photograph leaders who caused the problems and he would photograph the people suffering because of them. That was our constant. And I remem- ber the day I got word that he had died. It was my birthday, and I was printing a large scale print of Gad- hafi. So as I heard that my friend had just been killed by Gadhafi, there were his eyes staring at me. That felt like an acknowledgment that I’ve got to start doing more to cross the line and photograph people who have been robbed of power instead of just the leaders. Maybe I needed to step into Tim’s space.

ANDREA: Is that when you started changing your focus? How did your foundation come to be?

PLATON: I started before then, but this was the moment where things kicked into action. Human Rights Watch came to me a long time ago with a problem and they said, “Look, we’ve got all this data and no one’s interested in it. We’ve got all these horrible stories about human rights abuses, and we can’t get any of it in the press. Can you help us?”

And at the time, I wasn’t doing a lot of human rights work, I was more known for celebrating power and heroes. Covers of Rolling Stone, Esquire, that kind of thing. And they said there’s a forgotten country bru- talized by a military regime and we want to photograph and interview hundreds of people from there, former political prisoners, former torture victims, people from all walks of life. You know, there’s millions of NGOs like them around the world who are doing amazing work. I’ve worked with the United Na- tions. I’ve worked for Physicians for Human Rights. And we now are planning projects with the Marshall Project. But they have no resources for storytelling. Meanwhile, you’ve got media that is fundamentally disrupted, that has no resources to tell the important stories of our time. They’re just pandering to their readership, and they don’t want to challenge their readers because they’re worried about losing them. The most powerful people right now are ordinary people like us. The ones experiencing the reality of life, the ones changing history. Our leaders are chasing history, not changing it. They’re weak. They’re letting us down. Leadership is in complete crisis. If you want to talk about power, you have to go to the people being robbed of it, because they know more about it than anyone.

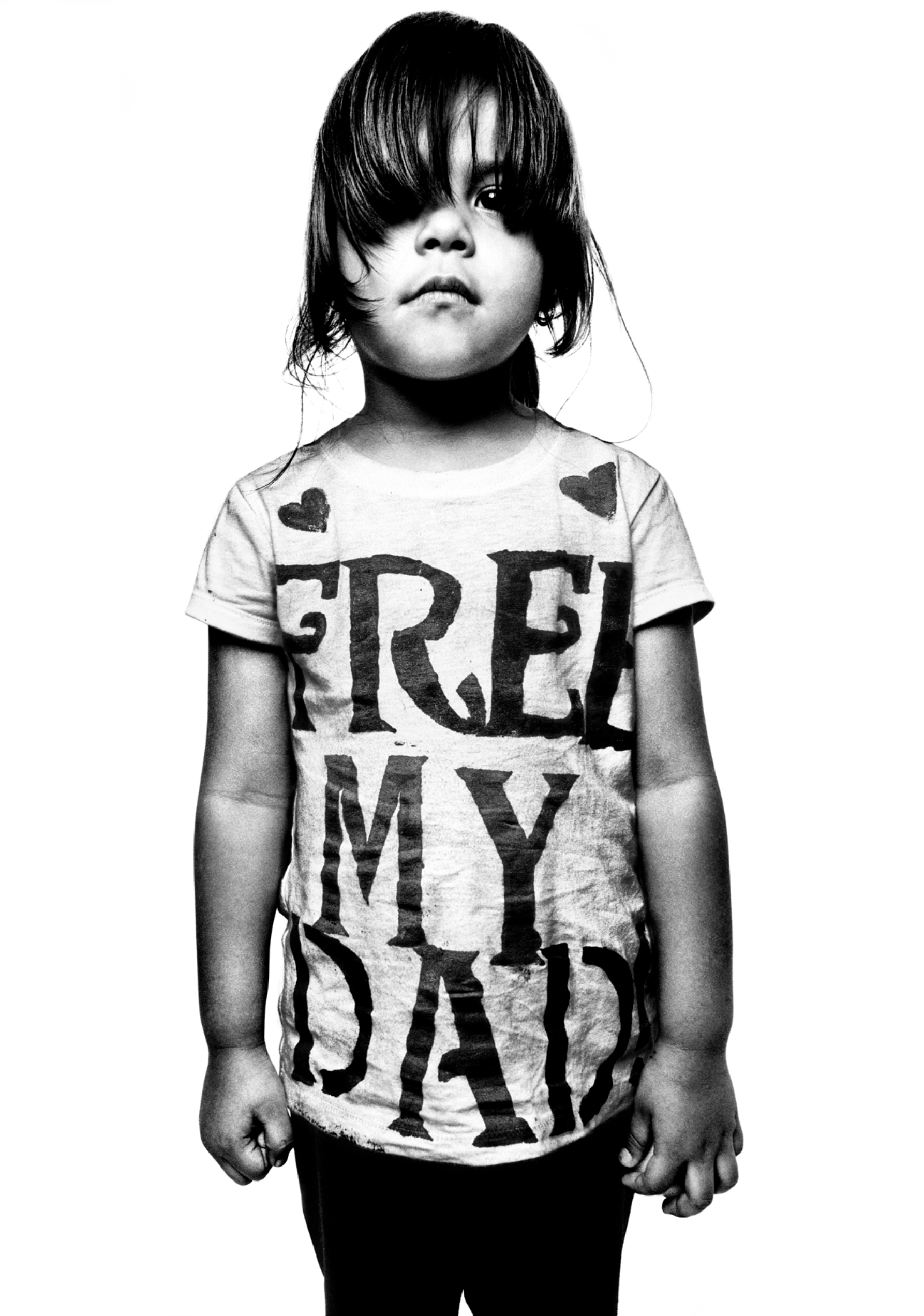

One day, I was at a pro-immigration reform march and I saw a mother marching with her three-year- old daughter named Evelyn. They were citizens, but the little girl’s father was not. He was undocu- mented, and he’d recently been put in a detention center awaiting deportation. Now, this little girl was wearing a t-shirt that said “Free My Dad.” There was a complete story in that picture, and it summed up how complicated things really are. We all want to be law-abiding citizens, so we try to follow our national laws. But there are also laws of universal compassion, and those two aren’t always in sync. And my job is to help illustrate the problem. So, I turned my camera to the little girl and she did what my kids would have done. She got spooked and hid behind her mother’s legs. But I didn’t want to show Evelyn as a victimized little girl hiding in the shadows of society, I wanted her how I’d seen her a few minutes ago marching with her mommy: proud, dignified, empowered and demanding change. So I had to earn her trust by playing balloons with her for five hours. I didn’t have to earn Obama’s trust. I didn’t have to earn Putin’s. But this little girl at the lowest end of society, in terms of authority, made me work so hard to earn hers.

ANDREA: Well, in stepping away from taking pictures of the powerful and moving to the ordinary, what do you think you’re going to leave behind?

PLATON: Hopefully, a set of stories that will help people understand the times they live in. In some cases, I hope my work instigated change in society or helped people articulate what they were already feeling. I speak a lot in front of large crowds and when they stand up at the end, they’re standing for what they are about to do. All I do is push the button.

Read the rest of the interview in Musée Magazine’s Issue No. 19 - Power.