From Our Archives: Stephen Shore

Stephen Shore, Granite, Oklahoma, July 1972.

William J. Simmons: In Stephen Shore: Survey, you and David Campany discuss your occupation of multiple genres, namely documentary and conceptualism. I want to take that one step further and think about your embodiment or your occupation of multiple historical strands in addition to genres. Looking back at your varied artistic production, I wanted to ask you, how can we think about the history of photography in a less segmented fashion? There are photographers like you who occupy multiple realms.

Stephen Shore: Beaumont Newhall was the first curator of photography at the Museum of Modern Art. He wrote The History of Photography, which went through many different editions, and in one of the earlier editions, the last chapter is called “Recent Trends.” He defines four trends: The document, the straight photograph, the formalist photograph, and the equivalent.

The document is obviously pointing at something in the world and saying, “This is something you should pay attention to.” And the straight photograph is the self-conscious work of art that says, “If you were to look at this image I’ve created, this is what you should pay attention to.” We extend this to the formalist photograph and the equivalent, to use Stieglitz’s term.

But what struck me is that, at the time, what I was looking at the most was Walker Evans, who is also the subject of Newhall’s first one-person exhibition. His pictures, to use your term occupy, occupy all four of Newhall’s trends. I think people recognize his work as a formalist experiment, as a document, and that he’s a self-conscious artist.

Perhaps the least understood is the equivalent. The one time I saw Evans speak was in 1972. The main theme of his talk was the term “transcendent documents.” So he was talking about his work, in a way, as equivalents – as an image standing for or embodying a state of mind. The one other thing I would add to that is something that Newhall didn’t mention; Evans also spoke of his work earlier, probably at the time he was making it, as photographing in documentary style. He was saying that he was adopting a visual language that has a cultural meaning, so that he could draw that cultural meaning to his work and explore it. And the reason I’m bringing all of this up is that when you talk about the Pictures Generation, I would think that Evans is a progenitor.

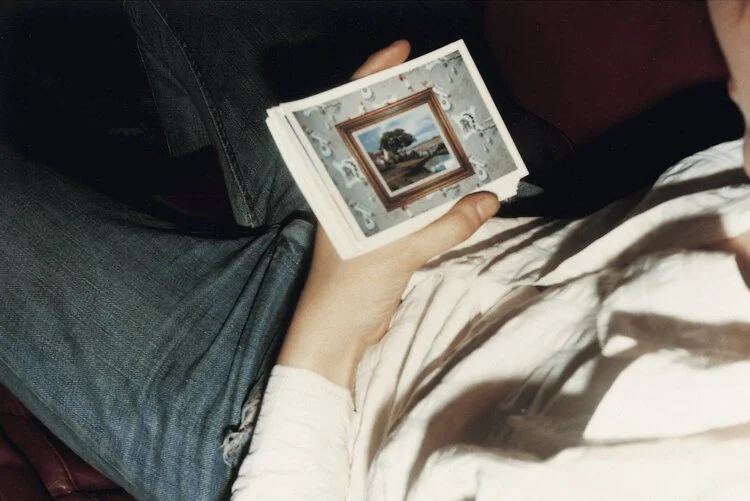

Stephen Shore, New York City, New York, March-April 1973.

Stephen Shore, Holbrook, Arizona, June 1972

William: It’s interesting, because I took a seminar on documentary photography at the Graduate Center taught by Siona Wilson, and the only artist of the Pictures Generation who was included was Martha Rosler. Considering what you just said, it makes me think that as scholars and critics look back retroactively, it seems that we impose a different relationship to that cultural documentary mode between, say, Walker Evans and Laurie Simmons. What is the nature of that shift?

Stephen: I’m not so sure that the shift is as dramatic as one would expect, and I think where the difference is that, to use Newhall’s framework, if a picture is only a document, and not a self-conscious work of art with no formal or structural intent, it comes across as an illustration. John Szarkowski once said, “An illustration is a photograph whose problems were solved before the picture was made.” So there is a gulf between, say, a certain kind of journalistic photographer and Walker Evans. That gulf between the journalistic photographer and Walker Evans may be greater than the distance between Walker Evans and Laurie Simmons, even though superficially, we might call both of their work documents.

Or to make it even more complicated, I teach with Gilles Peress, who is viewed as a photojournalist, but the aesthetic intent of his pictures is so sophisticated that I would say that there is an equally deep gulf between his view of photojournalism, and the kind of illustrative photojournalism you may find in typical magazines these days. And that kind of photography, which is entirely content driven, may cloud how people who are not photographers or people who don’t have a lot of experience in photography think about the intentions of other people who are doing pictures that are more complex.

What I mean by content driven is that…sometimes people send me pictures and say, “This is my version of one of your pictures.” And it may have a gas station in it, but it doesn’t look anything like mine. It’s not the way I would structure it, it’s not the way the light would look, and it’s not even the distance I would use. It looks nothing like one of my pictures. The only similarity is that it’s not a pretty landscape; it’s of an urban intersection or something. So I understand what these people are seeing when they look at my work – only the content. And they think that if their picture has a gas station in it, even though it doesn’t look vaguely like one of my pictures, then it will look like one of mine.

Stephen Shore, Luzzara, Italy, 1993.

Stephen Shore, Luzzara, Italy, 1993.

Another example is the architect and architectural writer Christopher Alexander. He wrote a book on aliveness in art, and I find his perception of architecture to be absolutely fascinating. As an example of aliveness, he uses a picture he took of this beautiful old Havana building, and then he juxtaposes it with an image of a rubble-strewn alley with some kids playing in it, and this is an example of a lack of aliveness. He’s not thinking of any formal relationships; the camera is simply pointing at something. And the picture of the alley is taut and beautiful and poetic. And so to my mind, it’s the exact opposite. Because, I’m seeing the whole picture and he’s only seeing what the picture is pointing to. There are those photographers who see that way, and in the minds of some people who really don’t grasp photography, they conflate people who are only pointing at things with people who are making complex images even though on a superficial level the pictures may look very similar.

For the full version of Stephen Shore’s interview, check out Issue No. 15 - Place.