From Our Archives: Zanele Muholi

Somnyama III, Paris, 2014. © Zanele Muholi

This interview was featured our 13th Issue: Women

Andrea Blanch: Why did you shoot these portraits in different locations and with different backgrounds?

Zanele Muholi: I don’t work in a studio; I work outdoors and I never use artificial light. I just move with the flow. There are a few major things that factor into my work. One of them is the subject. The people in my photos are participants, because they partake in a history-making project. Instead of calling them “subjects,” I call the people in my work “participants.” I work in an open space because I want any person who is interested in taking photographs to free themselves from all the expenses that are attached to photography—the freedom of being in an open space,frees you and allows you to be who you are. We don’t need to be confined in a space. It could be a portrait that is shot under a bridge. It could be a portrait that is shot after a party.

Andrea: What steps did you take to capture the personality of each person?

Zanele: Each and every person has a different way of looking and a different way of confronting you as you photograph them. And people dress in different ways. Different people want to look differently and I have to make sure they look good. How do we undo and undermine the images of the past? I like the fact that people look good, and that people have confidence with who they are.

Andrea: What do you mean by “looking good”?

Zanele: Presentable. To look at yourself, or an image of yourself, that you like at the end of the day. An image that your mother would like when she sees it. An image that a family member would remember as representative of you.

Andrea: Your work has been featured in museums and galleries around the world. What have the differ- ent reactions been according to the country in which your work is displayed?

Zanele: The reception has always been different be- cause each and every person who looks at the images looks for different things. I can’t say it’s the same for everybody. The reception has been good, and people are willing to know more about what is going on in South African LGBTIQ communities. The work is used beyond just the museum. Women and gender studies programs in different universities use this material, art history classes abroad and locally use this material, some visual anthropologists use this material. The work is now being used for educational purposes, which makes me happy.

Bona, Charlottesville, 2015. © Zanele Muholi

Andrea: How does your preparation and shooting process differ between photography and film? What aspects of each medium do you enjoy?

Zanele: I keep on saying to people, beyond just the process of making photographs, photography is about relationships. When I shoot, I’m not necessarily looking for ‘the best of the best’ of anything. For me, it’s more about creating, or establishing, a new relationship. In a human way, I’m not just photographing people, I’m trying to create the family that I never had. I want to establish a relationship with the human beings who are my participants, and also to maintain that relationship.

Andrea: How did you become involved with the LGBTIQ community and what drove the decision to portray persons who identify with the LGBTIQ community?

Zanele: I became involved with the LGBTIQ community because I am a Black lesbian. Therefore, I am able to write a history that speaks to me, or the many who are like me. We can’t depend on history to define us. We live our lives, and therefore, we have to de- fine ourselves. That means it’s not going to be done for you— you have to do it yourself. You have to be strong and educate others. That’s how I got involved. I didn’t see images that spoke to me as a Black lesbian. Therefore, I had to create them.

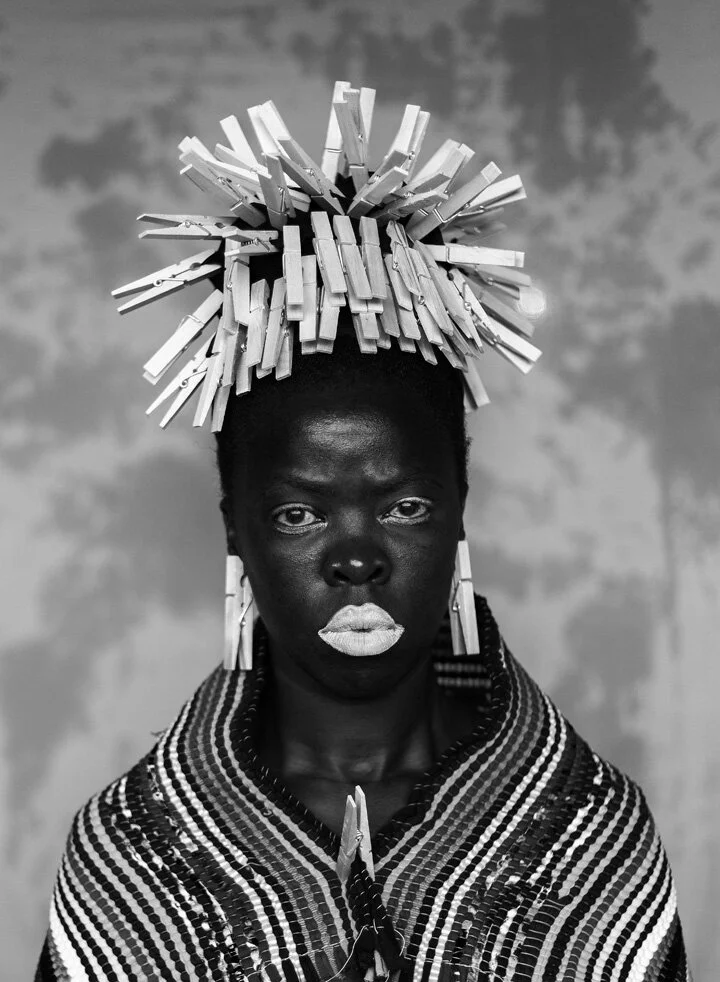

Ntozakhe II, Parktown, Johannesburg, 2016. © Zanele Muholi

Andrea: Let’s move on to Somnyama Ngonyama. In a New York Times article, you describe self-portraiture as, “confrontational, an inward examination bordering on violence.” You just said that you didn’t see images that spoke to you, so you had to create them. Despite this, you’ve rarely photographed yourself prior to this series. What prompted this shift to self-portraiture, and why were you previously hesitant to turn the camera on yourself?

Zanele: I have included myself in Faces and Phases. I was prompted to turn the camera on myself because it was a way in which I could work while traveling, as well as confront the politics of race and pigment in the photographic archive.

Andrea: Another major shift in this series from your earlier work is the use of studio lighting, sets, and costumes. Why did you decide to add these elements to this series? How do the different costumes relate to your self-exploration?

Zanele: Like I said before, all of the lighting is natural light. The props that I used in the photographs are all found materials from the venues I was staying in at the time of travel.

MaID III, Philadelphia, 2018. © Zanele Muholi

Andrea: Can you explain the meaning and origin of the series’ title, Somnyama Ngonyama?

Zanele: It means, “Hail, the Dark Lioness” and represents this newly personal approach.

Andrea: Do you plan on continuing with self-portraits, or do you feel you’ve accomplished all that you’ve wanted to with this series?

Zanele: I will continue with the series. I would like to reach 365 portraits.

Andrea: When did you start teaching photography?

Zanele: I share photography. I can’t say I teach photography. I share photography because I believe that every person should have a decent photo, and also that every person should be seen the way he or she wants to be seen. To be remembered, and also to be recognized. I’ve been teaching since 2004. I continue to share photography because I don’t think, looking at the population, that we have enough images. I think the archive would be richer if we had many faces, many portraits, many life-stories narrated visually. We’re making history. We’re making our voices heard. We’re making sure that those who come after us have something tangible.

Bester I (Mayotte), 2015. © Zanele Muholi

Andrea: In your opinion, how have the tensions between the white and black LGBTIQ communities changed in the last decade?

Zanele: I have too long a response to that question. That’s a problem in the West, that issue of “black and white.” So, I don’t want to talk about tensions between black and white. That’s a problem that’s currently happening in the States, where a lot of Black men are being killed daily. The issue about racial tensions, I would create a project to respond to that. I would respond by creating images that speak to that racial tension. It’s inappropriate for this interview. I have a girlfriend who is white. I am in love with a white woman. We talk politics and there’s nothing to hide. She’s quite knowledgeable when it comes to history and the oppressions of the past because she’s read history. It’s easy for us to talk about it.

See the full interview in our 13th Issue: Women