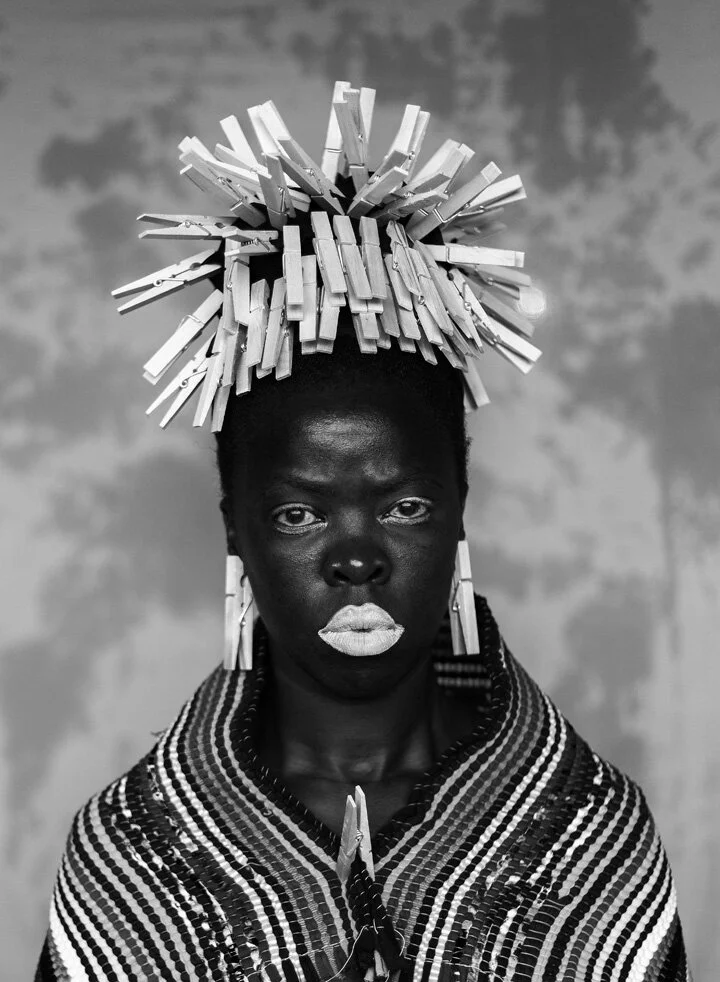

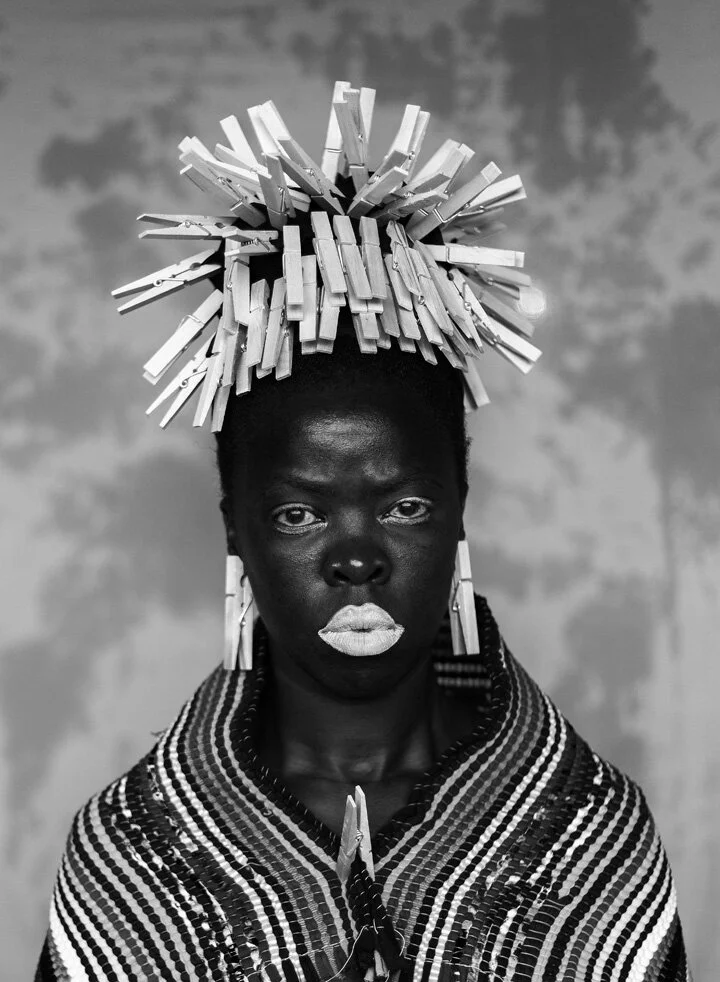

From Our Archives: Zanele Muholi

© Zanele Muholi

This interview was originally published in Issue 13: Women

ANDREA BLANCH: This past year, you’ve had two big shows in New York: one at the Brooklyn Museum, where you presented work from your Faces and Phases series, and your new show at Yancey Richardson, Somnyama Ngonyama. Let’s begin with the Brooklyn Museum show. What struggles did you face compiling the images for the installation?

ZANELE MUHOLI: Everything was planned in advance. So, I didn’t encounter any problems because it’s the work that I live with and it’s my work. There are 60 images exhibited, which is a very important number in South African history. 1960 is the year of the massacre, where people were killed in a place called Sharpeville. 60 images represent the 1960 Sharpeville Massacre.

ANDREA: What I found interesting at the Isibonelo/ Evidence exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum is how you chose to show the portraits with images of weddings and coffins–which was very moving, to say the least. Why did you decide to show those very disparate types of photography together?

ZANELE: Because they are like life. Between love and loss, between pain and joy—that’s how life is.

ANDREA: None of the photos in the collection display acts of violence, yet your video series does. Why did you make this decision?

ZANELE: There is one major image when you walk into the Brooklyn Museum of an ID book. An ID book is an identity document given to every South African citizen who is registered. When a person is killed or dead, it has to be recorded that the person is no longer alive. On the other side, you have the timeline of the victims of hate crimes. People don’t necessarily need to see graphic violence in spades. To present the pain of a mother who has lost her kid, that is violence. If you mean to say pain in terms of blood, I’ve seen a lot of those images. I didn’t want to show South African pain in that way. The document and the timeline is enough. When you walk into the space, and you read on the other side of the wall, you could see every coffin, you could see every rape, and you could imagine everything.

“Isibonelo” basically means “we have witnessed.” This is an example of our pain. This is an example of our experience. This is an example of our struggle. It is not a hundred percent of it, but this is just limited by space; otherwise, I would have said more.

ANDREA: Why did you shoot these portraits in different locations and with different backgrounds?

ZANELE: I don’t work in a studio; I work outdoors and I never use artificial light. I just move with the flow. There are a few major things that factor into my work. One of them is the subject. The people in my photos are participants, because they partake in a history-making project. Instead of calling them “subjects,” I call the people in my work “participants.” I work in an open space because I want any person who is interested in taking photographs to free themselves from all the expenses that are attached to photography—the freedom of being in an open space, frees you and allows you to be who you are. We don’t need to be confined in a space. It could be a portrait that is shot under a bridge. It could be a portrait that is shot after a party.

© Zanele Muholi

ANDREA: What steps did you take to capture the personality of each person?

ZANELE: Each and every person has a different way of looking and a different way of confronting you as you photograph them. And people dress in different ways. Different people want to look differently and I have to make sure they look good. How do we undo and undermine the images of the past? I like the fact that people look good, and that people have confi- dence with who they are.

ANDREA: What do you mean by “looking good”?

ZANELE: Presentable. To look at yourself, or an im- age of yourself, that you like at the end of the day. An image that your mother would like when she sees it. An image that a family member would remember as representative of you.

ANDREA: Your work has been featured in museums and galleries around the world. What have the differ- ent reactions been according to the country in which your work is displayed?

ZANELE: The reception has always been different be- cause each and every person who looks at the images looks for different things. I can’t say it’s the same for everybody. The reception has been good, and people are willing to know more about what is going on in South African LGBTIQ communities. The work is used beyond just the museum. Women and gender studies programs in different universities use this material, art history classes abroad and locally use this material, some visual anthropologists use this material. The work is now being used for educational purposes, which makes me happy.

© Zanele Muholi

ANDREA: How does your preparation and shooting process differ between photography and film? What aspects of each medium do you enjoy?

ZANELE: I keep on saying to people, beyond just the process of making photographs, photography is about relationships. When I shoot, I’m not necessarily looking for ‘the best of the best’ of anything. For me, it’s more about creating, or establishing, a new relationship. In a human way, I’m not just photographing people, I’m trying to create the family that I never had. I want to establish a relationship with the human beings who are my participants, and also to maintain that relationship.

ANDREA: How did you become involved with the LGBTIQ community and what drove the decision to portray persons who identify with the LGBTIQ community?

ZANELE: I became involved with the LGBTIQ com- munity because I am a Black lesbian. Therefore, I am able to write a history that speaks to me, or the many who are like me. We can’t depend on history to define us. We live our lives, and therefore, we have to de- fine ourselves. That means it’s not going to be done for you—you have to do it yourself. You have to be strong and educate others. That’s how I got involved. I didn’t see images that spoke to me as a Black les- bian. Therefore, I had to create them.

© Zanele Muholi

ANDREA: Let’s move on to Somnyama Ngonyama. In a New York Times article, you describe self-por- traiture as, “confrontational, an inward examination bordering on violence.” You just said that you didn’t see images that spoke to you, so you had to create them. Despite this, you’ve rarely photographed your- self prior to this series. What prompted this shift to self-portraiture, and why were you previously hesi- tant to turn the camera on yourself?

ZANELE: I have included myself in Faces and Phases. I was prompted to turn the camera on myself because it was a way in which I could work while traveling, as well as confront the politics of race and pigment in the photographic archive.

ANDREA: Another major shift in this series from your earlier work is the use of studio lighting, sets, and costumes. Why did you decide to add these ele- ments to this series? How do the different costumes relate to your self-exploration?

ZANELE: Like I said before, all of the lighting is natu- ral light. The props that I used in the photographs are all found materials from the venues I was staying in at the time of travel.

ANDREA: Can you explain the meaning and origin of the series’ title, Somnyama Ngonyama?

ZANELE: It means, “Hail, the Dark Lioness” and rep- resents this newly personal approach.

ANDREA: Do you plan on continuing with self- portraits, or do you feel you’ve accomplished all that you’ve wanted to with this series?

ZANELE: I will continue with the series. I would like to reach 365 portraits.

To read the rest of the interview, check out Issue 13: Women, here

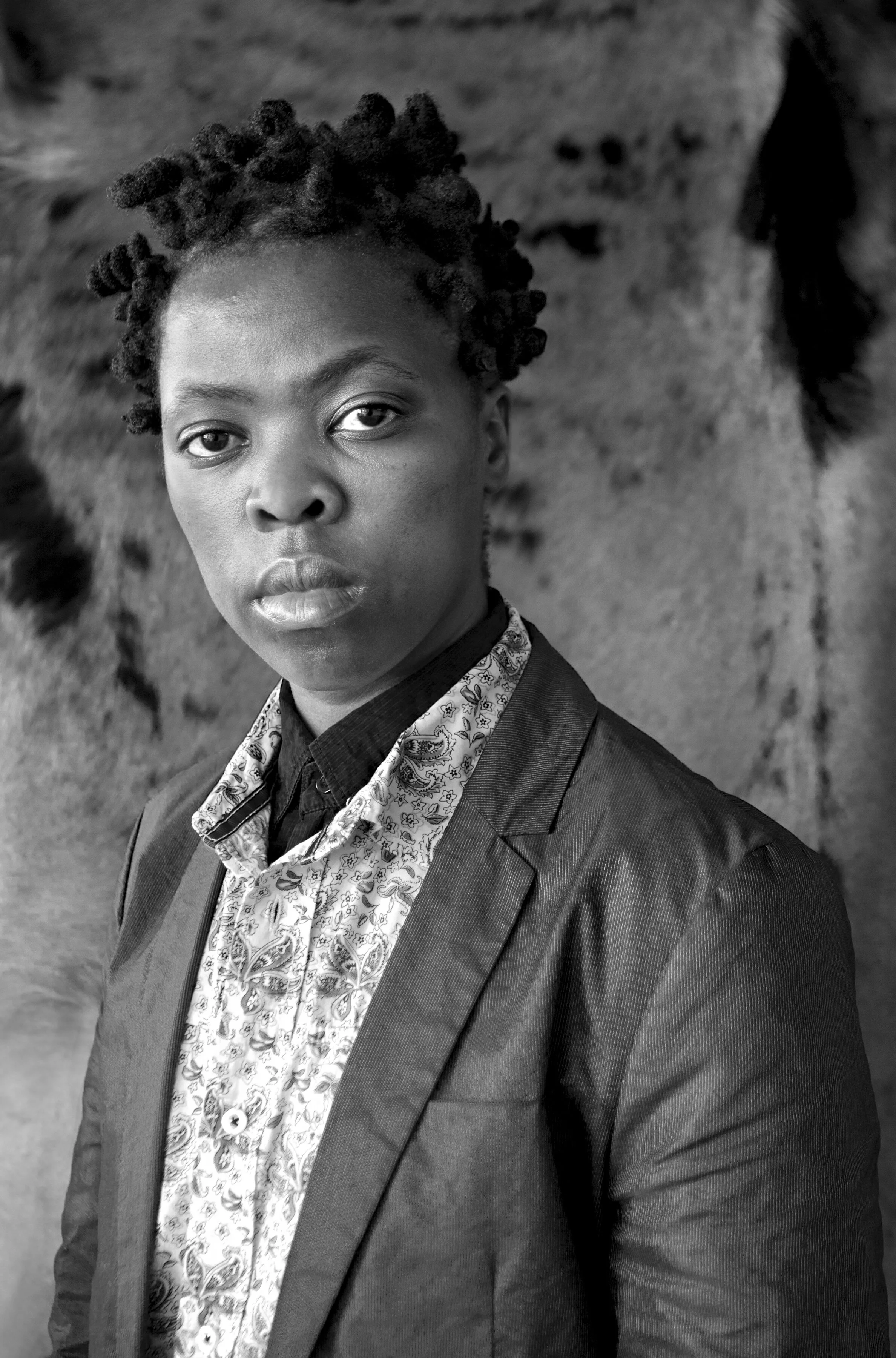

Portrait of the artist. All images © Zanele Muholi