Parallel Lines: Barbara Silbe

© Jacopo Scarabelli

Federica Belli: The language of photography is still among the most contemporary, despite the diffusion of new digital art forms and augmented reality. What factors make photography such a relevant medium in our time?

Barbara Silbe: Though not aware of it, we feed on photographs all the time. We are bombarded with photographs from the moment we get up in the morning, either via social media or via television. Above all, it is digital technology which has further spread the use of images. Paradoxically, this has leveled the quality of the photographs being created, in the sense that though bombarded, we are inattentive at the same time, given the continuous flow of the timeline of our social feeds. Even what might be touching in different conditions becomes superficial, thus getting lost in the flow. It is fundamental, in such circumstances, to train our ability to read images. Both as users and as photographers, since social networks have leveled our taste in terms of pictures: we like looking at hyper-saturated images and easy to read photographs. But one has to understand which one among the many is actually her voice.

F.B. After all, maintaining a direct contact with one's own voice and being able to remain true to one's own perspective is still fundamental in photography.

B.S. What matters is the truth. If you don't state the truth, you can't expect others to find themselves in the message you convey. And originality as well. Things that have already been said will never hit as hard as a new statement. You see, I sometimes teach photography. And I always give the example of this camera built to work exactly like a 3D printer connected to Google Images: it doesn't allow for a click if that photograph has already been taken by many cameras. Imagine how impactful and useful that would be for students! For those who want to think their work through and find their own point of view, it is essential to put effort into such process. There are hundreds of thousands of photographers in the world, but can you tell me something that no one has ever told me? Only then, you make me curious.

© Lee Jefferies, Courtesy Eyes Open!

F.B. Your work experience fluidly combines curating, journalism and teaching. You are therefore dealing as much with documentary photography as with fine-art photography. How is the relationship between the two photographic languages evolving?

B.S. The world of documentary photography finds itself with no reference points, since newspapers no longer have money. Up until the 1990s, a photojournalist would travel to Afghanistan and stay for six months - thus infiltrating in the social fabric of a place and bringing home both a macro-story and collateral narratives - while now it's all faster. I recently spoke with Lorenzo Tugnoli, a Pulitzer and World Press Photo winner. He is in Kabul, but only for two weeks at most, before being forced to return. And he works for the Washington Post! Neither agencies nor newspapers have funds for major reportages, not even the National Geographic. Photographers are self-financing and have to speed up their work. Also, photojournalists have learned to go after big international awards, which is what allows them to get funding to reinvest in their work. However, constantly looking for awards is a significant time-investment. Not only that, but this trend has also influenced the style of photography in recent years, as awards are often given to the photographer who shows the stronger, more impactful photography. Now people are looking directly for blood, while years ago people photographed war, avoiding blood. A great photographer that I published on EyesOpen!, Cristoph Bangert, recently published a book which particularly struck our editorial office: titled War Porn, the pages of the book are glued together. And it's a choice of self-censorship: the photographs are so strong that the viewer has to make a conscious choice: does she really want to see these images?

F.B. Being the director of EyesOpen! Magazine also means being in constant contact with the contemporary evolutions in photography. Which new developments in the use of photographic language are you particularly curious about?

B.S. Although I don't understand much about it yet, I am deeply fascinated by crypto-art. It has more to do with the financial world than the art world: it's actually about pixel investments. It's all new. Both collectors and artists basically care more about investments than art. I'm still reading up on it, so I won't suggest references of any kind, but it's definitely going to become an increasingly relevant industry. Having entered the industry of photography in the analog days, I still believe that in order to be fully experienced, photography must be printed. Even EyesOpen! Magazine was born as a paper magazine by choice. This world of NFTs is unsettling to anyone who conceives photography as such, yet I want to understand it. I have dived into it. In particular, Stefano Favaretto, one of the top experts about NFTs in Italy, holds regular meetings on Clubhouse to introduce his followers to this new environment. An environment that, no matter how strongly opposed, continues to grow

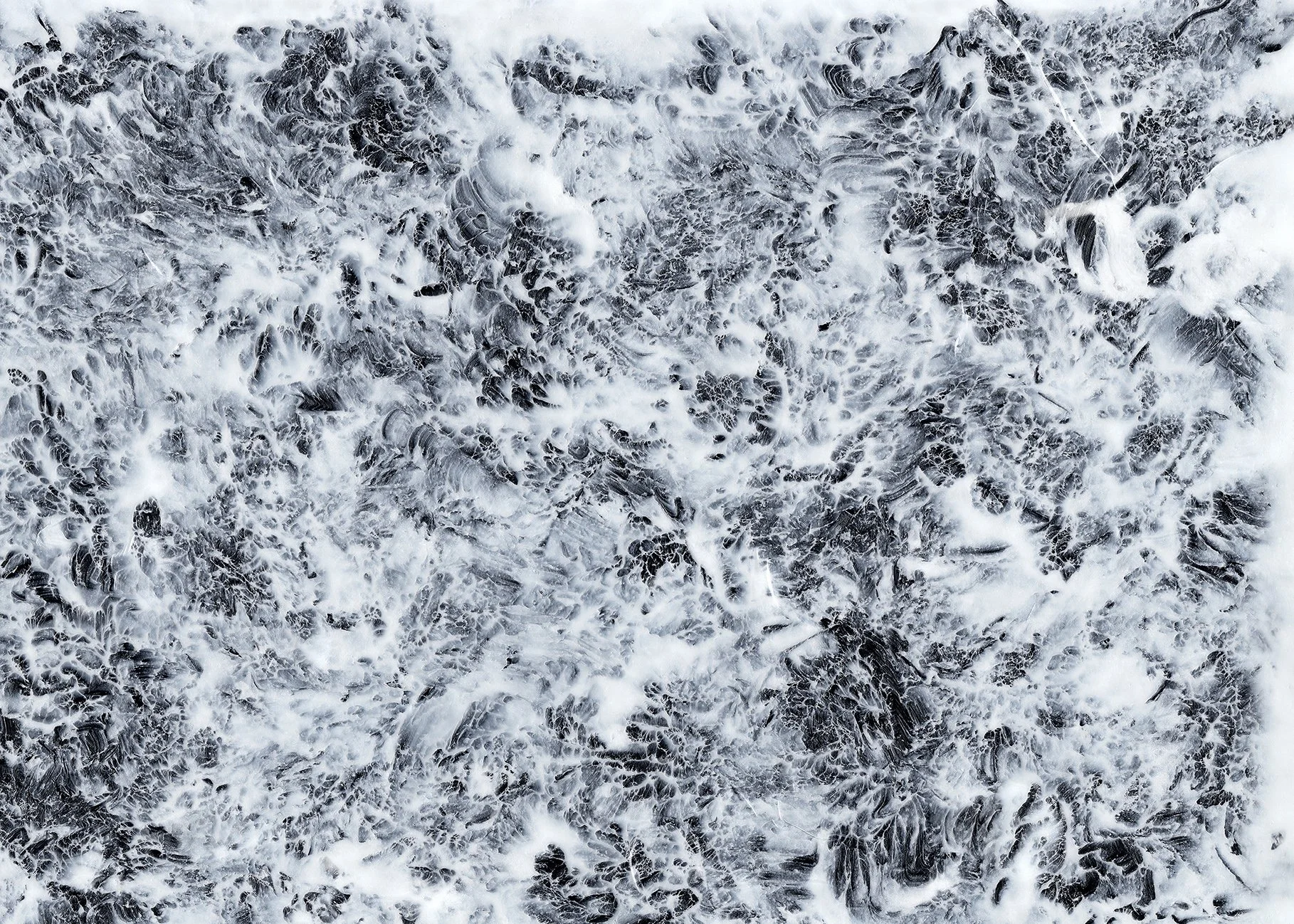

© Monia Marchionni

F.B. In publishing, we often hear about how the industry is in decline. For documentary photographers, it is becoming increasingly difficult to find an outlet for their work. How is the relationship between photography and publishing evolving?

B.S. Living the world of publishing from the inside, I see it constantly impoverished. Certainly a photographer can no longer count on the publishing industry to accommodate and support his work. In the 90s, the average expense for the monthly purchase of photographs was between 20 and 40 million lire. Nowadays any newspaper is openly in trouble: companies are not buying any advertising space, thus circulation is reduced and consequently so is the audience proposed to sponsors. Therefore, even less advertising space will be purchased in the future. Besides, nowadays, a cover pays a maximum of 500. Is it really worth it? Photography must be thought out in new ways, and all the great photographers have understood this. Many have moved abroad: Paolo Verzone, Lorenzo Tugnoli, and other great talents have turned to countries more suited to photography than Italy. Luckily, some extremely talented photographers have chosen to remain in Italy and create amazing work from here as well, such as Monia Marchionni, Jacopo Scarabelli and many others.

F.B. There are still some realities that sincerely believe in proposing emerging names, beyond the warranties of recognised photographers. Which are the media that most promote the work of emerging photographers and what is the role of professionals in stimulating a generational change?

B.S. I personally feel a sense of responsibility for this transition, to the point that I frequently scout photographers on Instagram as well. I'm constantly checking hashtags related to EyesOpen!. Even social media, often demonised by photographers from the analog days, now allows access to any professional. Magazines, agencies, critics, they all look at these digital showcases to enrich their gaze. They are a means of information which, if used methodically, respond to the demand for connection between young photographers and professionals. After all, it is not physically possible to answer all the emails you receive as a curator, not even by working 24 hours a day. Social media allows for a direct connection and has an immediate impact. I've noticed, in particular, that young women photographers are bringing out really amazing visions.

F.B. I do not doubt that they always have, back in the days as well, but the difference is that today we really have the means to make ourselves known. We can communicate photography and our conception of it. I still remember the first Photo Vogue Festival I attended physically. Walking out of the subway and being personally confronted with the visions of the women photographers who are part of the Female Gaze movement struck me with a disarming power. It made me think that it really is possible to have my own voice. And if it is possible to have one, I will.

B.S. Speaking of festivals, it is fundamental to introduce oneself and one's work on these occasions. Also because they allow you to create relationships that are very different from those established between a teacher and a student: often us curators are the ones who grow the most from this comparison, having new material to reflect on and the possibility to collaborate with new visions of the world. You can’t become a photographer by merely being behind the camera.

F.B. It is not easy to learn, yet I totally testify.