Parallel Lines: Andrea Tinterri

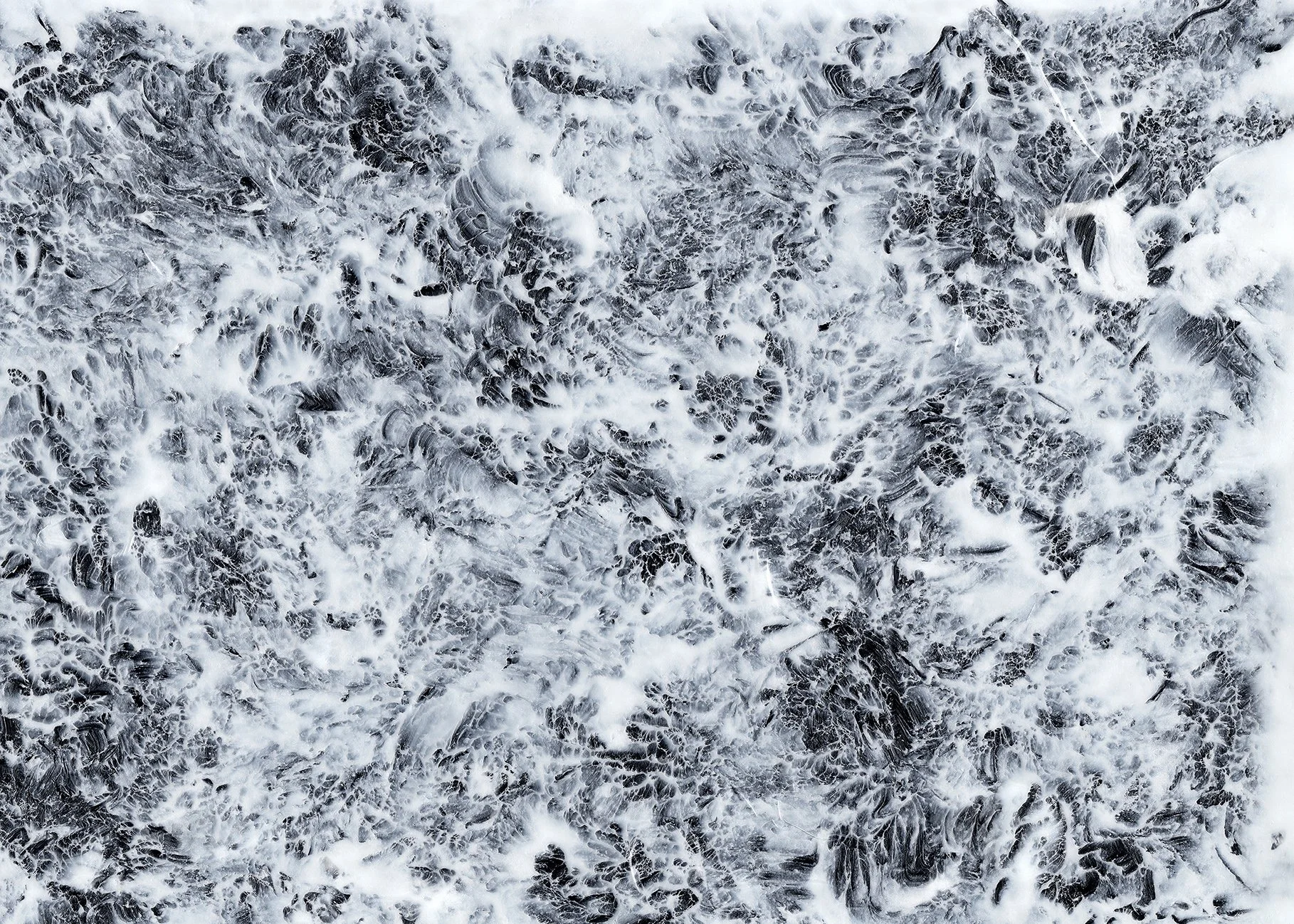

© Nicolò Cecchella

Federica Belli The language of photography is still among the most contemporary ones, despite the diffusion of new digital art forms and augmented reality experiments. Which factors make photography such a relevant medium in our time?

Andrea Tinterri Photography as a medium is less than 200 years old. When compared to the history of the image, it becomes clear how young and widely explorable it remains as a language. For instance, the decisive return to figurative painting currently taking place is just one of its cyclical reappearances. That being said, photography is a very wide stage, and the portion that flows into art – the one we are concerned with – is barely a small part of it. If photography really is such a relevant medium in our time, it is mostly due to the massive amount of daily photographs taken every day, photographs which influence our interpersonal relationships and the way we relate to the world around us. Even moving away from the present time – since the 20s, my family of studio photographers has made a living out of commissioned photographs both at weddings and public events – the prevalent form of photography has been the utilitarian one. And the same applies to authorial photography. Consider the advertising campaigns shot by the Alinari brothers, the postcards which have forever altered our perception of the Italian landscape, of the Farm Security Administration campaign which defined the American iconographic imagery. Those examples of utilitarian photography, both authorial and daily, have strongly influenced our way of perceiving and approaching the world.

F.B. It's an interesting definition, especially given the increasingly blurred line between the two levels of photography you mentioned. These two fields now influence each other, especially considering the use of massive photography as a starting point for its reworking in art photography. Think of Joan Fontcuberta, just to name a notable example. The possible developments are really wide.

A.T. And currently it is mostly daily photography influencing art photography, rather than the otherway around.

F.B. Your path as a critic has recently led you to explore the role of the spaces inhabited by art in the final fruition and reading of an artwork. What are the contemporary developments in the interaction between exposition spaces and photography? In which ways do spaces and the artworks it contains influence each other?

A.T. The discourse could be enlarged to works of art using any language, given the blurred boundaries between photography and other visual languages. During the lockdown, the debate around the role of spaces undoubtedly intensified, given the limited availability of accessible spaces which led to a greater use of online spaces and public areas. It has become necessary to abandon the traditional circuits of museums and the galleries. To this end, in collaboration with the Società Umanitaria in Milan, I developed a format entitled Appunti d'Arte to interview 12 insiders – artists, museum directors, critics and academics – on the topic of how photography and art can and should inhabit the spaces around us. The personalities involved, all quite young yet authoritative in their field – from Lorenzo Balbi to Emilio Bavarel, from Alessandro Sambini to Guido Segni and Cristina Sambero – generated a quite varied panorama. The most interesting aspect emerged is precisely the hybridisation between online and offline, two realities which are now indistinguishable. Every day we switch from one dimension to the other with extreme ease and without any trauma. This fact generates an important implication for exhibitions as well. For example, extending the discourse to contemporary art, one has to mention the Green Cube Gallery project by Guido Segni. This online platform hosts curators and artists for projects originating online but requiring an offline prosthesis. During the lockdown, paradoxically but understandably, they interrupted their activity: the offline portion, which should have brought the projects to fruition, would have been missing. Such hybridisation, a particularly important aspect today, generates new potential in terms of exhibition strategies.

F.B. In this way one compensates any shortcoming – if one can consider them as such – of both exhibition approaches. What happens online only is still perceived as partially unreal, while what happens offline only is now perceived as limited – both due to its temporary fruition and non- accessibility to the global public. This hybridisation also expands the possibilities in terms of exhibition imagination, both in the phase of creating new work and from a curatorial point of view. The book you recently published with Silvana Editoriale, 9 racconti tra arte e fotografia (9 stories between art and photography), focuses on the protagonists of the art world who have most influenced your path in the field of art. In what ways can you maximize the creative cross- pollination between curator and photographer?

A.T. Thank you for mentioning the book, I strongly value such work given its autobiographical intimacy. The book is structured around nine short stories which describe the meeting or the regular frequentations with these nine authors. Naturally, each relationship has evolved along a unique path, at times generating an ideal relationship based on a single, quick encounter – as in the case of Irma Blank, whom I met through a collaboration for the magazine La Foresta, and whom I already admired for her idea of writing and her disruptive practice; in such case a few hours were enough to generate a very strong story - and in others based on ongoing, friendly relationships – as in the case of Alessandro Sambini, Nicolò Cecchella, Stefano Serretta and Gianni Pezzani. In an extremely autobiographical way, far from an academic language, I also describe the nature of a relationship between curator and artist. A relationship that necessarily can and must be very intense, calibrated from time to time on the personalities involved. The lockdown period, with its stasis, reflection and discussion on the very role of art, has led some of these relationships to naturally intensify through the analysis themes. While not tied to any exhibition output, such repeated talks revealed to be preparatory for our subsequent path. Today the curator and the critic must think alongside the artists, imagining and building an iconographic system. As a result, a very intimate and confidential community is generated, within which exhibitions are then elaborated.

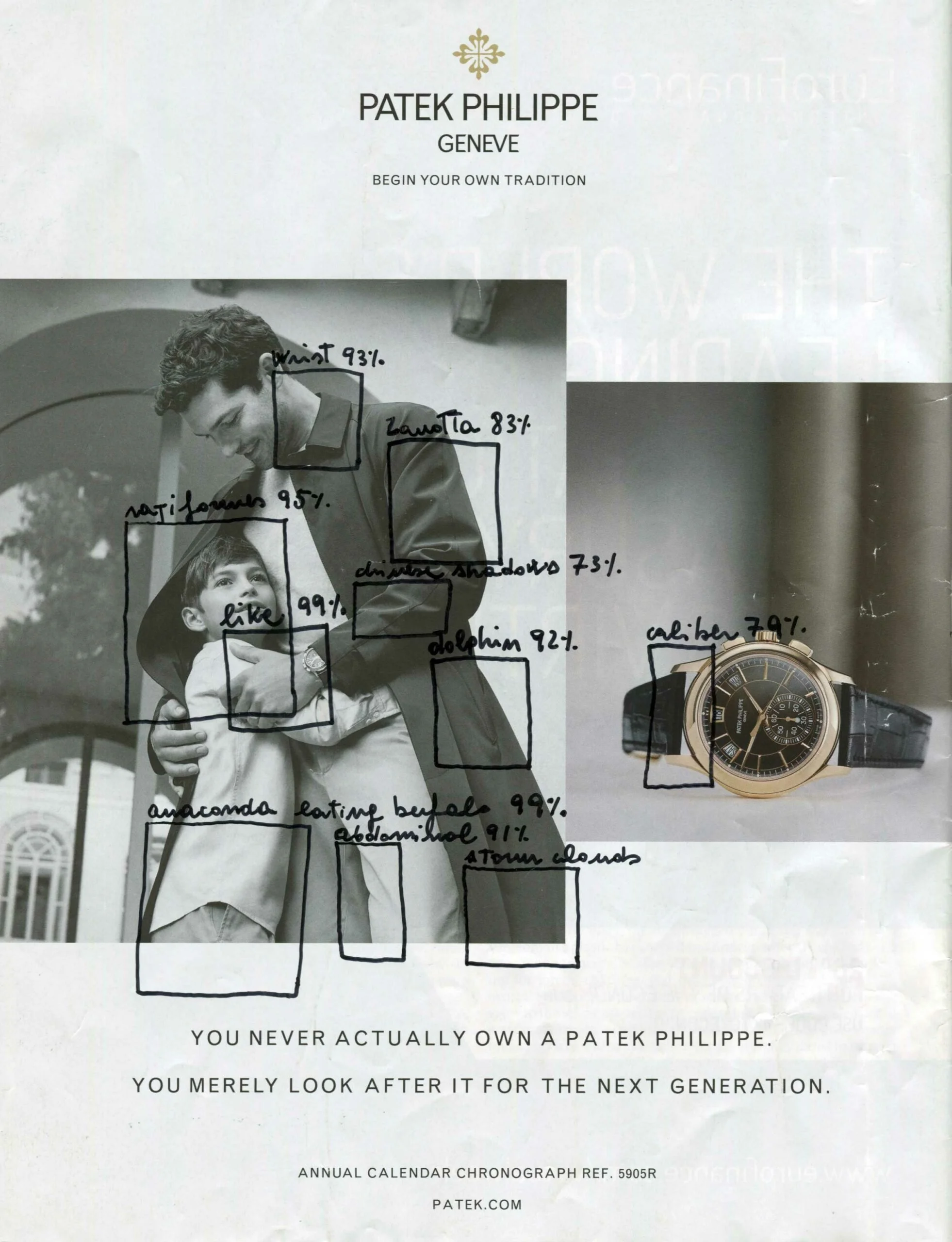

© Alessandro Sambini

F.B. Also because it is only in this intimacy that it is possible to compare the imaginative-creative perspective of an artist and the critical-theoretical one of a curator, on the topic of our contemporary reality as citizens and visual beings.

A.T. Oftentimes the projects imagined together end up being aborted. But even infertile research and failures are fundamental to the creation of such bond, such need for dialogue and speech that must characterise a critic as much as a curator and an artist. Each member of the art world must experience such need. Of course, one cannot forget the implications due to the fact that it is also a job, but one cannot miss the interpenetration it has with a hunger for confrontation. Failures are needed and comparisons leading nowhere are needed.

F.B. Failures are part of the journey of anyone entering our field, given the experimental nature of art which, in itself, implies the possibility of failure. It remains a job, yet it has as much of a job as of the need for self-expression. And as such it cannot have schedules or definitions. Your work as a curator and critic focuses on Italian photographers born around the 80s. Specifically, one of the directions recently embraced in photography is post-photography. In which ways are these artists expanding the definition of photography in the contemporary landscape?

A.T. I maintain relations above all with Italian artists who, though still young, already have a defined path and recognisable poetics. The field in which Italian photography operates at the moment is very wide and heterogeneous, ranging from the recovery of a landscape photography rooted in the imagery of the Viaggio in Italia created in the 70s – though strongly re-imagined and remastered – to experimentation in the post-photographic field. The latter involves all those artists and image operators who, starting from photography or at least including it in their research, feel the need to expand and explode its boundaries to involve other disciplines – even other than art languages, such as science and philosophy. Among the others, Alessandro Sambini, Nicolò Cecchella, The Cool Couple, Irene Fenara, Rachele Maistriello, Alessandro Calabrese and Giorgio Di Noto come to mind; artists who include photography in their research, but only in order to take it to its extreme consequences and explore its controversies. Sometimes photography remains only in the form of conceptual heritage, a language from the past of these artists who now turn to new media. These shadows, however, remain fundamental and evident in the projects they carry out. All these narratives can be inscribed in the post-photographic universe, a sort of consequence of photography that coexists as much with more traditional photography as with the billions of selfies taken daily. Indeed, the post-photographer often draws and steals iconographic material from the internet in order to recode and study it, rather than taking his own photographs. This pliability remains extremely fascinating, naturally leading to reflections on iconographic ecology and the need – or not – to take new photographs.