“American Power was kind of a lament. It was stressful because of the physical and psychological challenges that the work entailed and the restraints that I faced.”[1]

Mitch Epstein’s American Power, a highly politicized project that investigates the processes surrounding the creation of energy, was (ironically) an exhausting experience for the Massachusetts-born photographer. In an attempt to avoid being one-dimensional, and perhaps maintain his sanity, Epstein chose to pursue his fascination with trees, documenting a multitude of these wooden giants throughout the Five Boroughs in his latest collection, New York Arbor. However, it can be said that New York Arbor, like its predecessor, is illustrative of its own kinetic energy: the power of these deciduous urbanites to speak volumes and tell stories through their mere existence, to serve as humble reminders of New York City’s past, present, and future.

One aspect of Epstein’s work that is immediately evident is the idiosyncratic nature of each tree. These growths succeed in transmitting singular, unrepeatable vibes and characters. It is this uniqueness that is paramount to the power of New York Arbor: the trees are anthropomorphized, because they are in the context of an urban landscape. Isolated, away from a mass of greenery, these trees gain the ability to cast an image all their own. In this manner, they become emblematic of New York City itself, as well. As Epstein puts it, “Along the way I realized the city had a much more diverse range of tree species than I had realized. Many of them were immigrant trees, non-native trees,”[2] trees that, according to New York Arbor’s official site, were brought to America as diplomatic gifts or souvenirs from around the globe. These fragile, yet monumental plants are evocative of New York City’s underpinnings, of the countless immigrants who have constructed a city with such a diverse background.

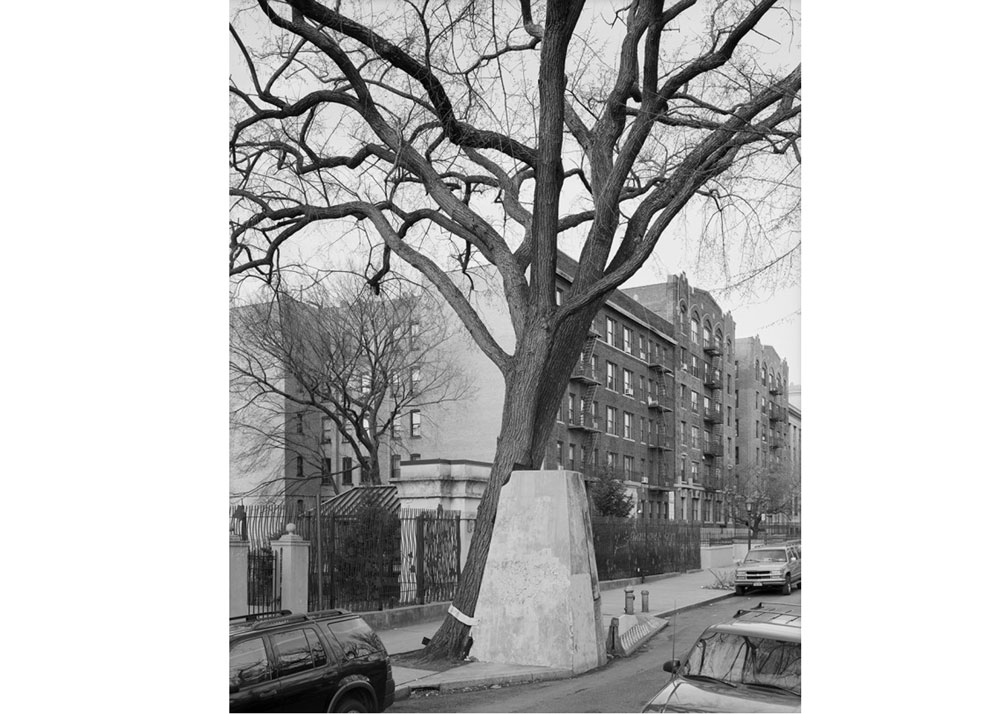

While Epstein shot New York Arbor throughout the 2011-2012 year, attempting to capture trees during the different seasons and in different lights, I find his wintry photographs to be the most telling and intimate of the compilation. The deciduous trees are seen without foliage and, as I just mentioned, are bare and fragile. When one looks at these, dare I say, candid images, one is imbued with a sense of revelation almost as if one has seen the skeleton or soul of the tree. Epstein’s decision to shoot in black-and-white removes, for those trees that do have their leaves, anything that can distract from the trees’ architecture. The emphasis is placed on the process of shaping. There is an undeniable humanistic quality inherent in New York Arbor.

New York Arbor’s raison d'être is obviously the trees, yet, Epstein’s work also highlights the relationship they have with the city, noting the push and pull that takes place between a tree and its concrete surroundings. Take for instance, this American Elm Tree located in Brooklyn (above). A cement barrier is required to impede the tree’s downward “progress,” a fruitless attempt to reign in the wooden leviathan’s raw energy, its natural power. However, this image can also be viewed as a study of symbiosis: the city (this time in reference to those who live there) goes to great lengths to ensure survival of the tree. This effort is made in the city’s self-interest, though, for without these trees this metropolis would be zapped of comfort on a very human level, mired in questions of true character. Epstein beautifully captures this sentiment in his description: “The cumulative effect of these photographs is to invert people’s usual view of their city: trees no longer function as background, but instead dominate the human life and architecture around them.”[3]

At the heart of the trees’ power there lies constancy. These growths, having been planted over a century ago and having survived, exist now in a new context. Much of New York Arbor evokes feelings of nostalgia, a reflexive response. The longer one looks at these photos, the more one realizes that these trees will remain long after he/she has passed away. In this fashion, the trees become symbols of the future, too. Constants.

Epstein seems to reference this everlasting power, even if only tangentially: “But then, when I look back I’m struck by the fact that even then [in my youth] I was interested in environmental issues. Thirty-five years later that became a central theme in my work. I find that interesting.”[4]

[1] Heleen Rodiers, “Mitch Epstein: Big Apple trees,” Agenda Magazine, April 30th, 2013.

[2] Rodiers, “Mitch Epstein.”

[3] John Mahoney, “A Fresh Look At…Trees?,” American Photo, May 7th, 2013.

[4] Rodiers, “Mitch Epstein.”

Review by Paul Longo