Fashioning Self: The Photography of Everyday Expression | Phoenix Art Museum

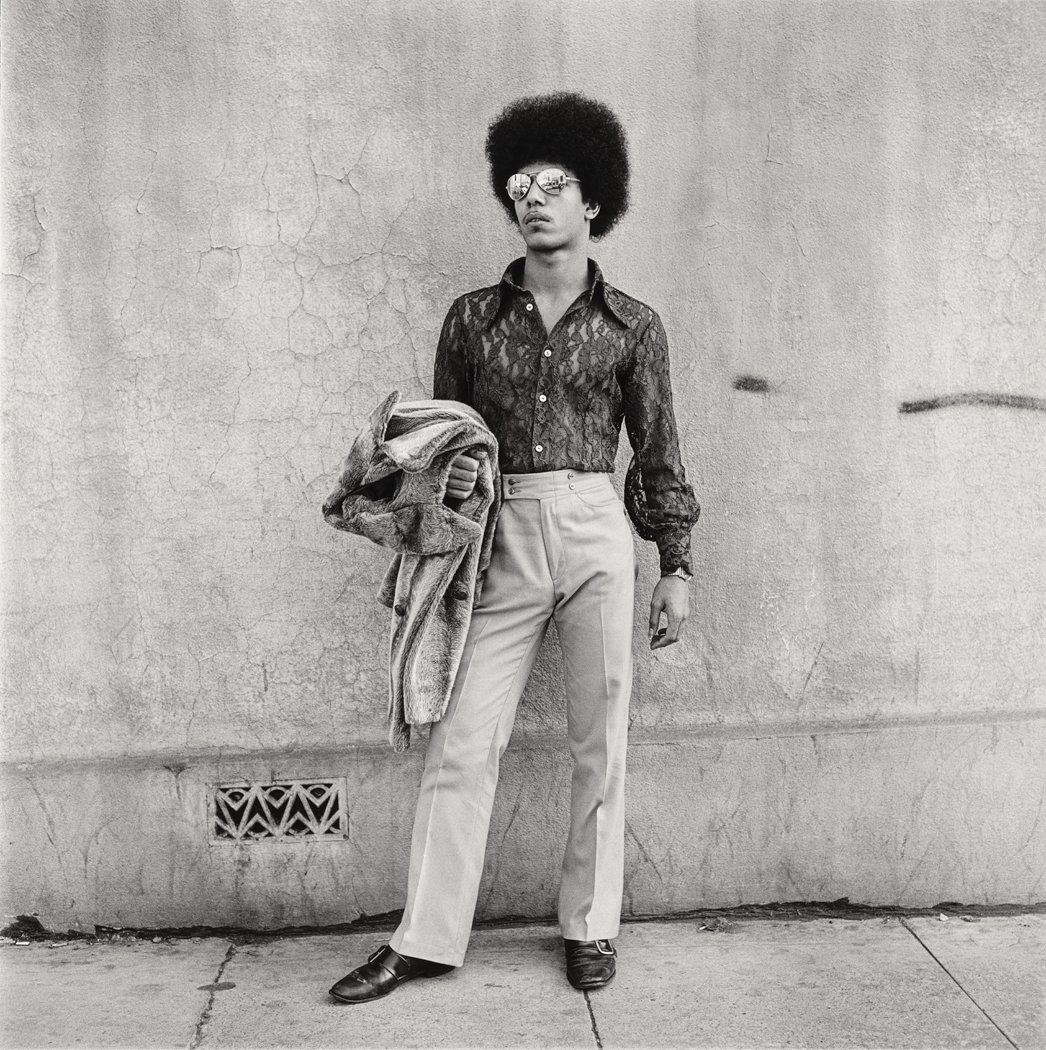

Dennis Feldman, Man with Reflective Glasses, 1969-1972. Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona: Gift of the artist. © Dennis Feldman.

Written by Michael Galati

In the digital age, your online presence is a form of social currency: it informs who you attract, how you’re perceived and how you intend to be perceived. The impetus to present yourself in a particular way through photography, however, did not begin with Instagram. In fact, this kind of social posturing has been part of the social experience for generations. An exhibition at the Phoenix Art Museum, Fashioning Self: The Photography of Everyday Expression interrogates the relationship between the modes through which people have chosen to present themselves aesthetically, emotionally and socially and what the camera actually reveals, even if what the camera sees was not necessarily anticipated by its subjects. Organized by the Center for Creative Photography and featuring 54 works of street, documentary, and self-portrait photography taken from 1912 to 2015, the exhibit chronicles a history of self-expression, reveals what is often hidden by curation, and questions whether emotional authenticity is possible in a self-consciously postured image. Fashioning Self is on display until November 5th.

Kozo Miyoshi, Tucson, Arizona, 1992. Gelatin silver print. Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona: Gift of the artist, DEP’T CO.,LTD., Tokyo, Nippon Polaroid, Tsudani Oil Co. Ltd.© Kozo Miyosh.

An exhibit conscious of the social and cultural norms that influence portraiture, Fashioning Self is able to elicit what the subject intends to both show and hide. The above picture, resembling an image that could be found in a modern day Hinge profile, exudes masculine energy: the rodeo garb, the identical and ostensibly nonchalant stances that draw the eye’s attention to the exaggerated broadness of the men’s chest and shoulders, and the omnipresent physical non-interaction between them. It’s a photo that was taken with a masculine idea of what the female gaze wants to see.

Another gaze, though, may see a celebration of fraternity for fraternity’s sake. Notice the smizes that tell more than they show, the desire to present likeness amongst one’s social circle, and the unspoken limit in the spectrum of individual self-expression, for example. Of course, what a viewer interprets from an image depends on what attitudes or experiences that viewer brings to the picture. But the same could be said about the subjects, which is part of the point. A standout piece in the exhibition, this image holds in it both what is present and what is not and is the exhibition’s exemplar of the camera seeing the pot when its subjects only see gold.

Joan Liftin, American, Drive-in Owners, North Carolina, 1987. Chromogenic print. Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona: Gift of Helen Levitt. © Joan Liftin

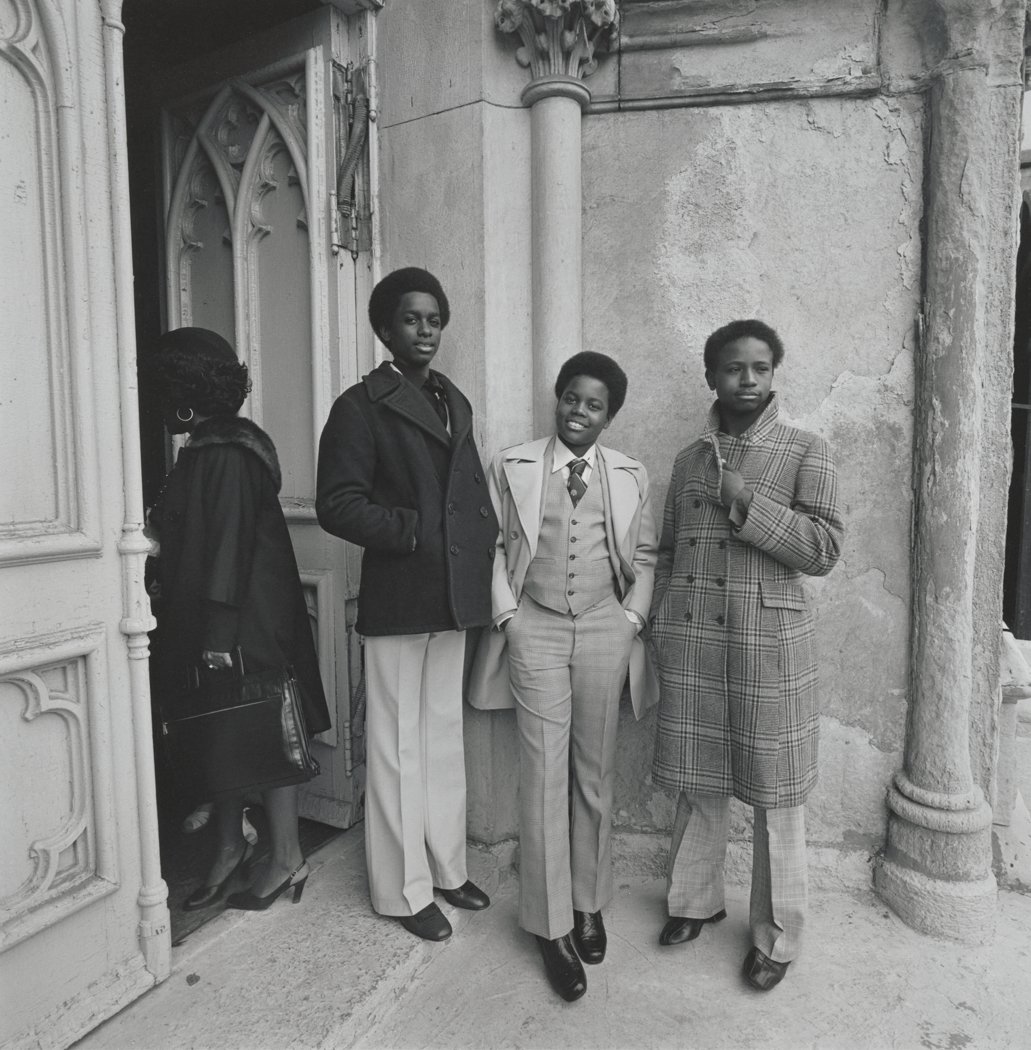

Laura Volkerding, Easter, Chicago, 1979. Gelatin silver print. Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona: Laura Volkerding Archive © Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona Foundation.

On the other end of the spectrum of images whose subjects intend to project one thing but project another are images whose subjects are aware of the gazes they’re projecting and receiving. In images like these, posturing becomes the focus of the image, unhidden by social norms and fully embracing such a performance. The image above features three young boys dressed in their Sunday Best for Easter in Chicago. Whether or not they were dressed by their mothers for this occasion, their presentation is part of the intent of the image: the boys are proud of how they look and are not using their pride for a purpose other than to celebrate their appearance for the occasion. The unsteady stance of the boy on the right adds a bit of awkwardness, possibly a result of maternal coercion, but this only contributes to the earnestness of the photo. Here, the intended gaze of the camera and its subjects are one. In this way, Fashioning Self shows that emotional authenticity is possible in social posturing; the two are not mutually exclusive, but depend on the integrity of the subject and their gaze.

Another aspect among many that is intriguing about Fashioning Self is its interaction with contemporary photo sharing over social media. Patrons are encouraged to take selfies and other portraits of themselves at the exhibit and post them to social media using the hashtag #FashioningSelf. In doing so, the exhibit actively participates in the relationship between subject and gaze: its patrons display to an audience a particular persona of them at a museum about persona.

Max Yavno, Untitled, 1947. Gelatin silver print. Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona: Max Yavno Archive. © Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona

A kind of take on a pre-modern selfie, the above image makes a similar meta move to the museum’s call to action to its patrons. Like a selfie, the subject is curating a particular persona of themselves with a particular gaze in mind. However, where modern selfies are mostly curated to catch the like of a crush, this self-portrait intends to make emotional interiority the subject of its gaze, though indirectly.

The subject positions himself in front of a painting of a woman whose facial expression resembles his: distraught, yearning, pensive. This could be read as an intentionally constructed self-reflection: he sees himself in the woman and is putting a mirror up to himself, thus telling his viewers how he feels. The gaze, however, is broken. It is the woman in the painting whose gaze meets the camera, while the subject’s is averted. In this way, he is using a second object to reveal how he feels. This image, then, recalls the first referenced photograph, Tucson, Arizona (1992), where certain emotional qualities are displayed while others are ostensibly hidden. Yet, where these images diverge is that this image itself reveals that its subject wants to hide his emotions and, through this posturing, projects those very emotions. The subject sees himself through the painting who sees the camera seeing him; he’s posturing through another object but is conscious that he is doing so. And so, the subject retains emotional integrity because he is self-consciously using the posturing to tell the viewer how he feels.

Joan Liftin, American, 70-40, Clairsville, Ohio, 1978. Dye coupler print. Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona: Gift of artist. © Joan Liftin

Through a comprehensive array of portraits and self portraits of individuals with varying gazes, postures, and social contexts, Fashioning Self shows that it is possible to retain emotional integrity in constructed images, but only if the subject is aware of this move and does not try to hide its intended gaze. It’s an exhibition that is curious about the origins of the desire to present oneself in photography, a desire that has been exponentially amplified by social media. Coming at a time when our online lives may feel more real than our in-person lives, Fashioning Self calls us to reflect on what we’re showing and what we’re hiding when we assemble ourselves in a particular way, especially when we think the camera sees what we want it to see.