Exhibition Review: Robert Longo: The Destroyer Cycle at Metro Pictures

Untitled (Raft at Sea), 2016 - 2017 triptych; charcoal on mounted paper

By: Madeleine Leddy

When Musée’s Steve Miller interviewed multimedia artist Robert Longo back in March of 2016, Longo talked a lot about death. “We are trying to deny death, to look it in the face and say I’m not scared,” he said, speaking on behalf of artists like Hanne Darboven, but also discussing influence from thinkers like Walter Benjamin and Roland Barthes. It is clear, from Longo’s latest work—particularly the massive charcoal pieces he has finished since giving that interview—that his later work has much in common with the poststructuralist tendencies of Benjamin and Barthes, (both of whom wrote a fair amount on photography as a medium and practice) than it does with any particular artistic movement to which critics have linked Longo, from Abstract Expressionism to Pop Art.

Viewing Longo’s work shows the extent to which curating it, let alone creating it, must have been an intellectual exercise. The photos of which Longo works all contain messages of some sort—some overtly political, some more ambiguous. The process of translating the (usually color) images to black and white charcoal entails important choices about what aspects of the image will be emphasized in the new form; like a linguistic translator, Longo bears the burden of deciding what nuances he will maintain, how he will maintain them, and what facets of the image he will choose to emphasize. In his case, nuances of color rather than words. But colors, in an image, function in an analogous way to words in prose.

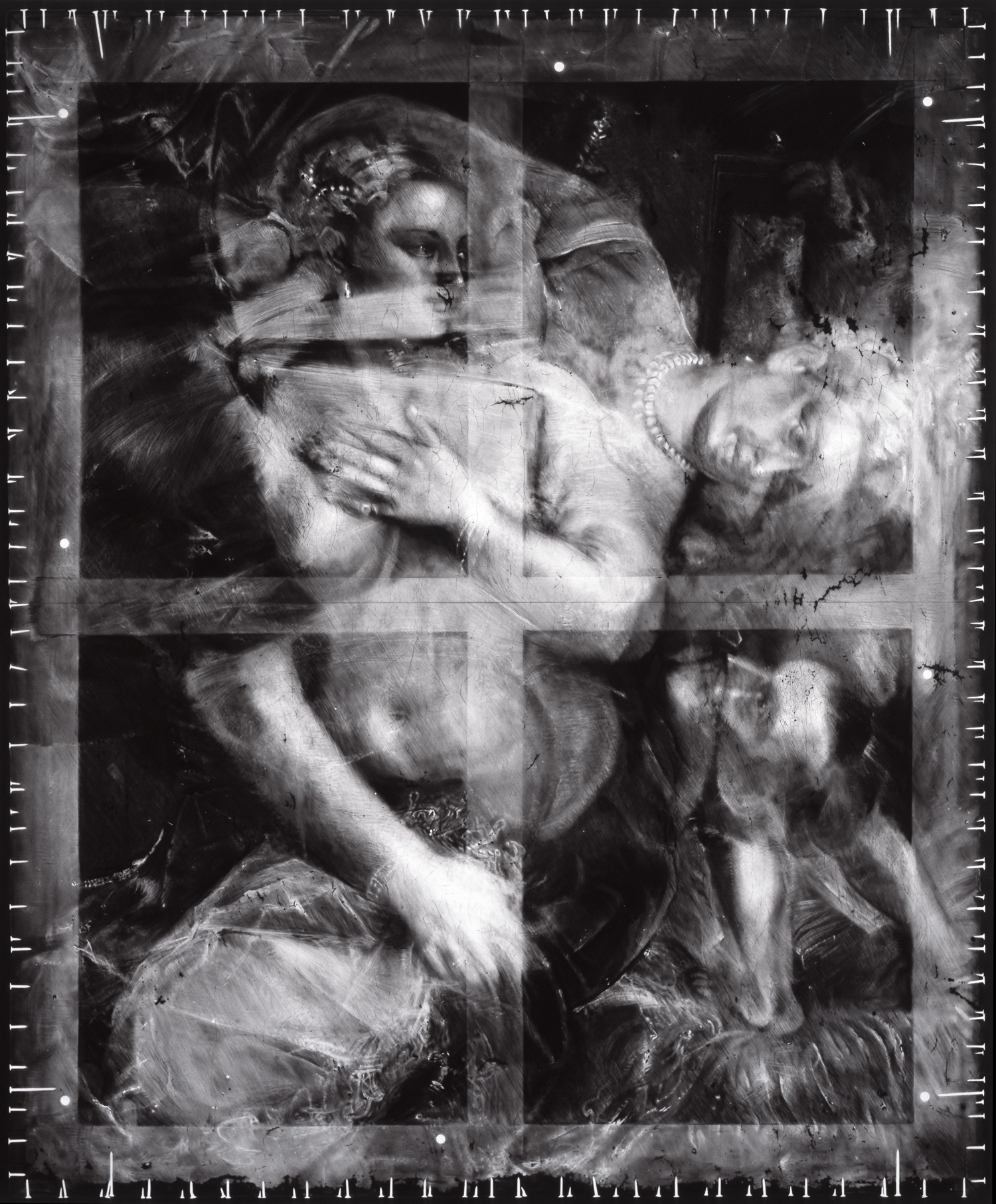

Untitled (X-Ray of Venus with a Mirror, 1555, After Titian), 2016 - 2017 charcoal on mounted paper

The tactile nature of charcoal allows Longo to add a dimension to his works, which are photorealist from afar, and more impressionistic up close. At the details where he wants to add emphasis, Longo piles on the black powder; this creates slightly three-dimensional contours that, paradoxically, make the work of art itself seem more real, but its content more abstract.

So how is it that Longo’s translation of a photograph as powerful as the newspaper shot of five St. Louis Rams players in “hands up, don’t shoot” formation on the field, or of a precarious refugee-filled raft tossing in a seemingly endless gray sea, can be even more arresting than the original image itself ? The philosophical roots of Longo’s process give the charcoal productions a story, even, in a way, a raison d’être, but there is something even more sobering in every experience of looking at these huge, monochrome projections of images that should look familiar to us but, in this new form, do not.

Untitled (Nov. 8, 2016), 2016 charcoal on mounted paper

The answer to this question may be best attempted from the starting point of one of the seemingly very apolitical works of the show, Longo’s study of an x-ray of Titian’s Venus with a Mirror (1555). His fascination with x-rays of famous works of art, as he noted in an interview with Kaleidoscope, stems from his engagement with Benjamin’s The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Production, and embodies his consistent insertion of himself as an artist into the realm of critical theory. By blowing up a copy of Titian’s painting and revealing the layers of lacquered-over sketches behind the visible picture, Longo provides himself with a ghostly template for his charcoal translation—and, unsurprisingly, the rendering of the x-ray in black and white only augments this quality of ghostliness. Two hidden figures, one apparently male, the other female, both adults, emerge in the shadows behind Titian’s finished Venus, and Longo appears to have chosen to emphasize their presence as voyeurs, darkening and thickening the contours that define their faces and groping hands, while fading out the now-vulnerable Venus. Venus seems to have lost agency, and all this at the fault of a technological maneuver that Titian, himself, could not likely have dreamed of—and that Longo, in an exercise of his own agency, has used to reconfigure the artist’s intentions.

The exhibit’s pièces de résistance, however, were not necessarily those that engaged with archaic art. These ones—that had a group of high school students on a gallery visit crowding for a better view—were given ample space to shine: the three-panel refugee boat downstairs, and a pair of dialoguing works upstairs: one of a darkened American flag, the other, positioned on the opposite wall, of a cracked iPhone screen taken in close-up.

Untitled (Shattered iPhone Screen), 2016 charcoal on mounted paper

The refugee boat photo, pulled from a Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders/MSF) flyer, is as evocative in its subject matter as in its portrayal: here, Longo’s charcoal shadows the eyes of the raft riders’ faces, some of which are visible to us as they look over their shoulders. The eyes become black sockets, an effect perhaps best captured in Longo’s smoky medium. His choice to use a piece of photojournalism as his base for this work, as well, recalls his ongoing engagement with Benjaminian thought: while journalism is, in an ideal world, supposed to be an objective practice—and on-the-fly, unstaged photojournalism made possible by increasingly agile technology. It is still a means of capturing a moment that will have an effect on the world, and cannot be totally free of the capturer’s (journalist’s or photojournalist’s) subjectivity.

The upstairs portion of the installation, which consists of Untitled (Nov. 8, 2016) (the American flag work), Untitled (Shattered iPhone Screen), and Study of Lights Out, which depicts an eerie backlit shadow of the Statue of Liberty, is a small room that is almost dwarfed by the wall-length works; and it is in this intimate space that the viewer is confronted with, perhaps, the most striking, even though ambiguous, symbolism of Longo’s message. We are confronted with America, literally in black and white, and she is—if this part of the installation is conceived as a small whole, a coherent sub-message—on the verge of cracking. Standing in front of the glass-protected Untitled (Shattered iPhone Screen), you can see the reflection of the American flag from its facing wall—and it looks broken. Lady Liberty, a few meters to the side, offers more of an omen than a beam of hope. In fact, she seems contemplative—much like the viewer, lost in the infinite reflection between cracked iPhone screen and American flag—and much like Longo himself, we can imagine. These are images that force us to think about what living in the twenty first century means for art, and consider the damage society has inflicted upon itself. Art can make us contemplate these things, but cannot fix them independently.