Soviet Architecture: The Style of Communist Utopia

Aleksandr Rodchenko, Guard, Shukhov Tower, 1929

Nailya Alexander Gallery presents The Art of Photography and Architecture in Soviet Russia: 1920s-1930s

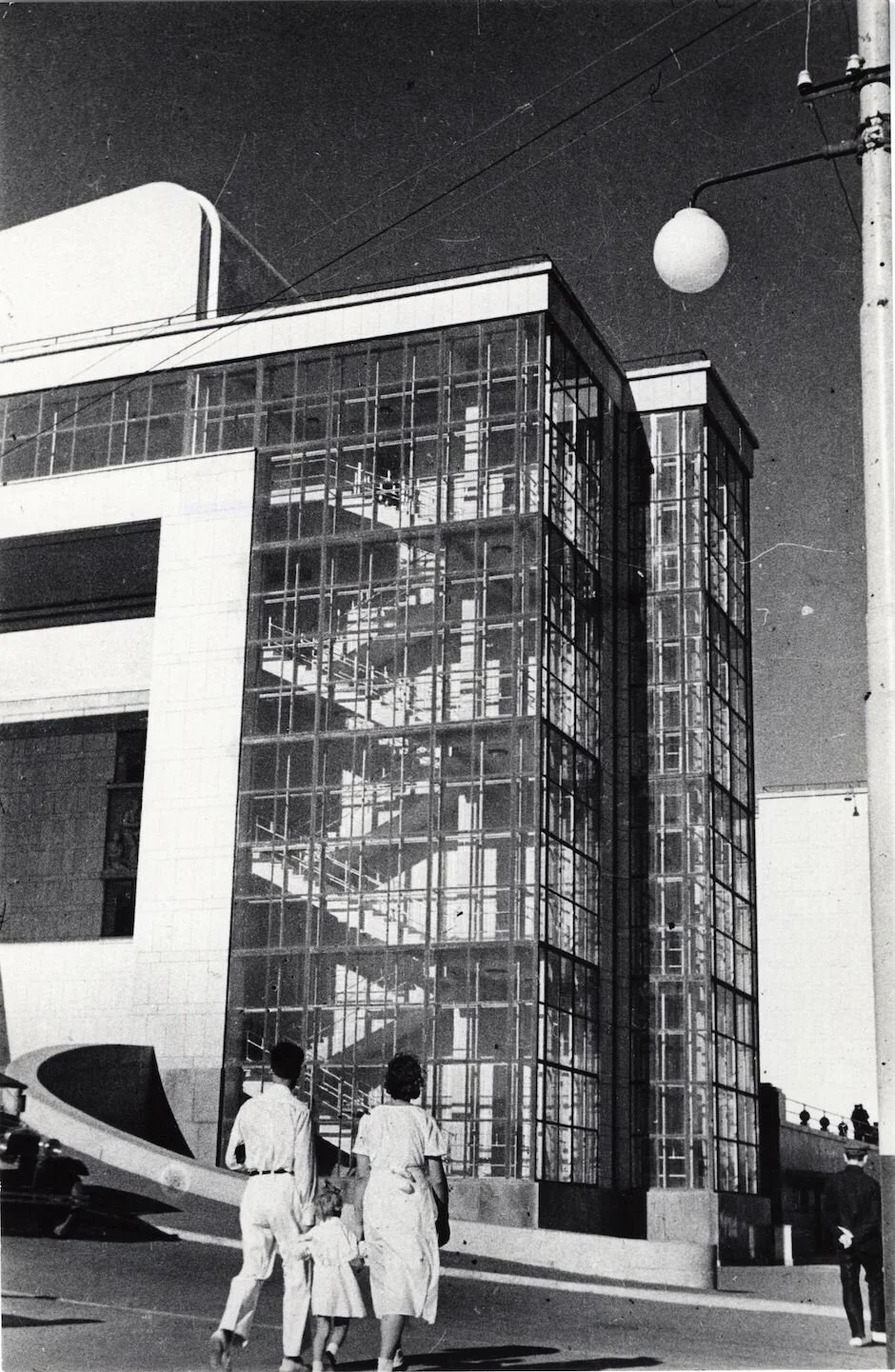

A new political ideology requires a new aesthetic to go with it. This was the claim by Soviet architects and designers that worked in the 1920s to remake the built environment of the USSR. The young Soviet architects who searched for new ways of dwelling, habitation, and working, developed a style with functional and clear geometries void of decoration and hierarchy. In their mind, the architecture that was later named constructivism had to be as radical as the utopian political system that was still being implemented.

Architecture has always served the role of manifesting current political and cultural ideas. The communists in the USSR wanted to emancipate the workers and deliver equal and healthy environments that would give workers a place to realize themselves through communal and artistic activities.

Boris Ignatovich, Bakhmet'ev Garage, 1933

Boris Ignatovich, In the Sublunary World, 1937

The architecture was dynamic and fragmented, not following any kind of predetermined composition. The important thing was the creation of spaces that would promote and inspire novel ways of socializing and give public spaces strong visual identities.

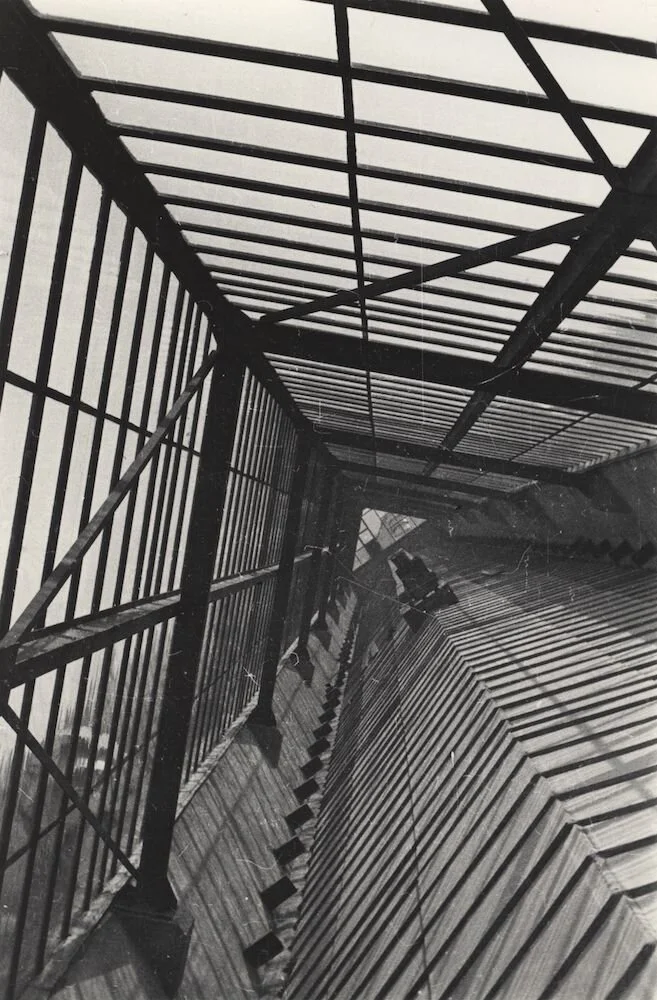

The geometric forms of steel and concrete coupled with dramatic artificial lights gave photographers plenty to work with. Instead of being tied down to standard angles and compositions that were needed to capture the rigidity and symmetry of premodern buildings, photographers working with the new constructivist architecture could experiment with compositions of strong graphic quality. Movement—through strong diagonal lines—became the dominant concept for these images. Stagnancy and hierarchy were left for the old world.

Boris Ignatovich, Floors, 1928

Arkady Shaikhet, From Upstairs, New Apartments at the Usachevka Housing Complex, Moscow, 1928

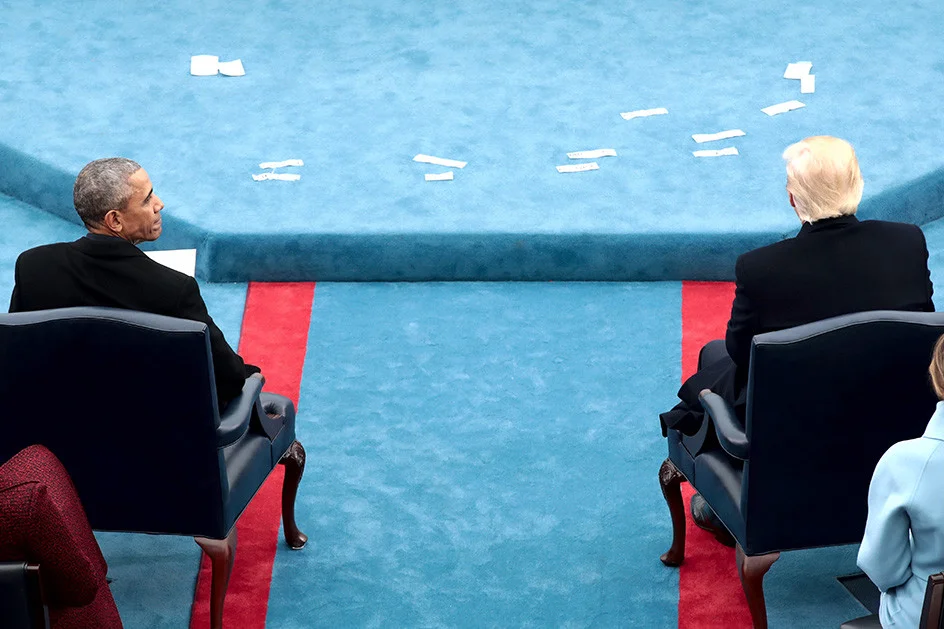

The aesthetics of a political ideology reveals a lot about its core values and how it wants people to feel, and so it’s easy to see the changes in Soviet politics that took place when Stalin began consolidating power. The constructivist architecture was dropped for a return to conservative and hierarchical architecture filled with superfluous decoration.

A similar action can be observed in our times in the United States where the Trump government mandated a return to classical architecture in order to “make architecture beautiful again”. The Trumpian aesthetic is gold draped, flashy, and boasting, telling a lot about how Trump sees himself and what his government thinks America should be about.

Arkady Shaikhet, From Downstairs, New Apartments at the Usachevka Housing Complex, Moscow, 1928

Georgy Petrusov, View from Airplane (the Derzhprom), Kharkov, 1930

The visual style of architecture, photography, and the aesthetic objects we surround us with are often tied to a political power who wants us to see and feel the world in a certain way. That is why it will always be relevant to look back and get inspired by brilliant artists of the past. The Soviet architects and their photography collaborators are a good example of that showing us how the world could also look.

See the online exhibition of Soviet Architecture at Nailya Alexander Gallery.

Ivan Shagin, Palace of the Soviets station, c. 1935