The exact origins of Russian prison tattoos remains cloudy, however, they started appearing with in- creasing regularity in the early decades of the twentieth century. The practice was banned, forcing prisoners to get creative with their process. Urine, blood, and melted rubber formed a makeshift ink that would make even the toughest devotee cringe today. By the waning years of the Soviet Union, tattoos had become a typical means for prisoners to express their identities in a remarkably complex manner. Bodies were read like books, epics of lives sculpted under an oppressive regime that offered little allowance of individual expression. An agreed upon system of symbols were rigorously adhered to in order to create a working language of ink on skin. One could look at the body of a fellow inmate and know his or her crimes, affiliations, and prison history without ever speaking a word.

Recent interest in Russian prison tattoos is largely due to the sketches of former Leningrad prison warden, Danzig Baldaev. Between 1948 and 1986, Baldaev recorded the tattoos of countless inmates, constructing a gigantic archive of the culture. In 2004, FUEL, a British publishing house, began turning Baldaev’s drawings into the three-volume Russian Criminal Tattoo Encyclopaedia, moving the clandes- tine language into the public sphere.

The authenticity of Baldaev’s sketches are confirmed by the later work of press photographer, Sergei Vasiliev who photographed prisoners incarcerated throughout Chelyabinsk, Nizhny Tagil, Perm, and St. Petersburg between 1989 and 1993. Vasiliev’s photographs reinstate a human element to the iconog- raphy. While Baldaev’s drawings distill the practice into a neat set of symbols, Vasiliev’s photographs foreground the identities of the individuals depicted in the images. Each photograph is accompanied by location where the prisoner was found, adding to the evidentiary character of the archive.

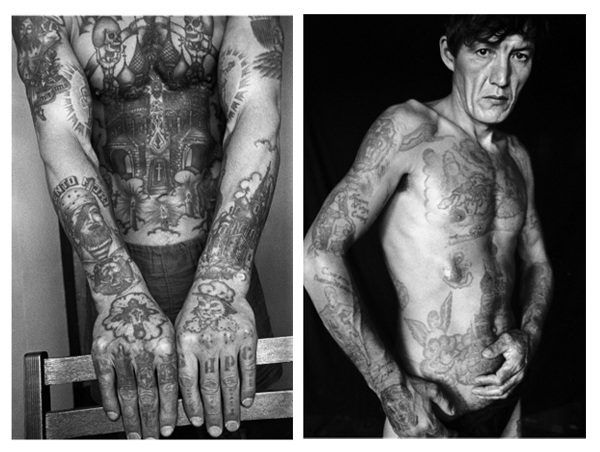

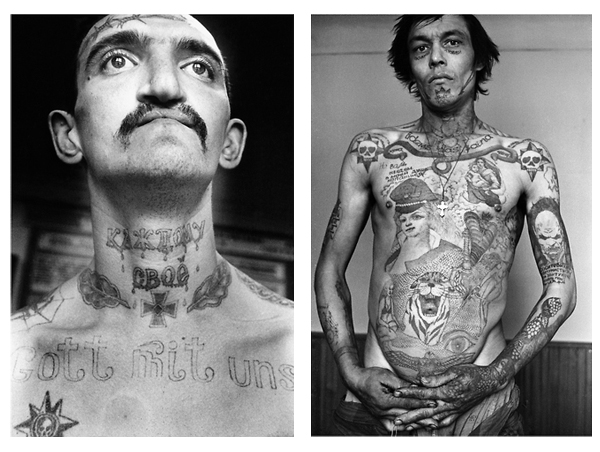

The bodies in Vasiliev’s photographs provide a sense of scale for the tattoos. While some prisoners allocated their entire chest for a single image, others reveal aggregations of small pieces acquired over many years of imprisonment. The location of specific subjects on the body was rarely random. Images of Stalin and Lenin appear with regularity on chests as it was thought that firing squads were prohib- ited from shooting at images of the two leaders. Insects depicted on the palms of hands marked the identity of a pickpocket. Upon committing a murder while incarcerated, a prisoner could have a knife tattooed on his neck to signify availability for hired killing. Tattoos on fingers became a quick way to convey status if the rest of the body was covered.

The signifying function of each subject remained relatively consistent, but the sourcing of images var- ied from the work of Renaissance masters to the prisoner’s own designs. Both men and women ap- pear in Vasiliev’s archive, emphasizing the significance of the practice across the prison population. In many cases image was combined with text, further solidifying meaning and lending the tattoo a more personal connection to its bearer.

Far removed from the distanced gaze of the prison guard, Vasiliev’s photographs convey the psycholo- gies of his subjects in a remarkably candid fashion. Here, the the tattoos articulate histories only hinted at in the encyclopaedia. At the same time, they confirm the existence of the practice and challenge viewers to decipher their meanings.

Sergei Vasiliev. Strict Regime Corrective Labour Colony No.9. Gorelovo Settlement, Leningrad Region. 1989 ; Sergei Vasiliev. Corrective Labour Colony No.6. Farnosovo, Chelyabinsk Region. 1992.

Sergei Vasiliev. Corrective Labour Colony No.5. Nizhny Tagil, Sverdlovsk Region. 1991 ; Sergei Vasiliev. Strict Regime Forest Camp Vachel Settlement. Penza Region. 1993.

Photographs from the Russian Criminal Tattoo Encyclopaedia Volumes I-III (FUEL Publishing). Portrait and all photographs © FUEL / Sergei Vasiliev