Image Above: Jacques Henri Lartigue, Agay, Cap du Dramont, 1919

Jacques Henri Lartigue was given a camera at seven-years-old, just after the turn of the century. He main- tained, even into artistic maturity, boyish instincts: a naive, playful eye, even the probing curiosity of sexual adolescence, an exploration-by-exertion. Lartigue peeks into private spaces catches people in those absent- minded, intimate moments before they are able to compose themselves. He prods them, opens them up, and documents their response. The camera is not invisible or disconnected from these photographs; it has a solid, intrusive presence. He uses his camera to provoke his subjects, who often, playing along, look back.

©Jacques Henri Lartigue (Left: Audemars on Blériot, Vichy, 15 September 1912; Right: Mr Folletête (Plitt) and Tupy, 24 March 1912)

©Jacques Henri Lartigue (Left: Audemars on Blériot, Vichy, 15 September 1912; Right: Mr Folletête (Plitt) and Tupy, 24 March 1912)

©Jacques Henri Lartigue (Anna la Pradvina, Avenue du Bois de Boulogne, 15 January 1911)

©Jacques Henri Lartigue (Anna la Pradvina, Avenue du Bois de Boulogne, 15 January 1911)

The camera was still relatively new. It was just gaining prominence and commercial availability. Photog- raphy was still developing a vocabulary. Tracking Lartigue’s childhood photographs onward, one gets the sense of the artist coming to terms with a new technology in the same way one gains familiarity with one’s body in infancy: by playing with it and testing its limits. Lartigue had the fortunate advantage of en- countering an art yet unencumbered by form and convention. His relationship with the camera was pure and instinctual, and both together, man and machine, helped define a vocabulary of images that, with the advent of film and television, was to become the dominant language of that century and our own. Lartigue often shot his subjects in motion. He sought out the state between each staged moment, the state of upheaval: kinetic, imperfect, and forever transitory. Figures jumping, skipping, falling, flying; dresses fluidly skimming the air; dust condensing into clouds around tires; water sprouting from the legs of divers. Subjects are pinned mid-air, eternally airborne beneath the thin surface of the image. He conjured up this floating, transient world that drifts delicately beneath the rigid, cohesive one. Lartigue captured the spirit of an Icarian generation, which, undergoing its own moment of sexual curios- ity, was anxiously thrusting itself skyward, first in planes, then rockets. Lartigue photographed early flight attempts. Like his many photographs of people jumping, he depicts the subjects of these pictures still in the air, stuck in the moment before they fall. This is the other meaning of the Myth: what is the fall compared with the ecstasy of flight? Lartigue was concerned primarily with flight, a participation in life unhindered. Lartigue was a diarist. Being a diarist means that the separation of art from one’s life and one’s body is, at best, negligible.

Pages from Lartigue's Diary

Pages from Lartigue's Diary

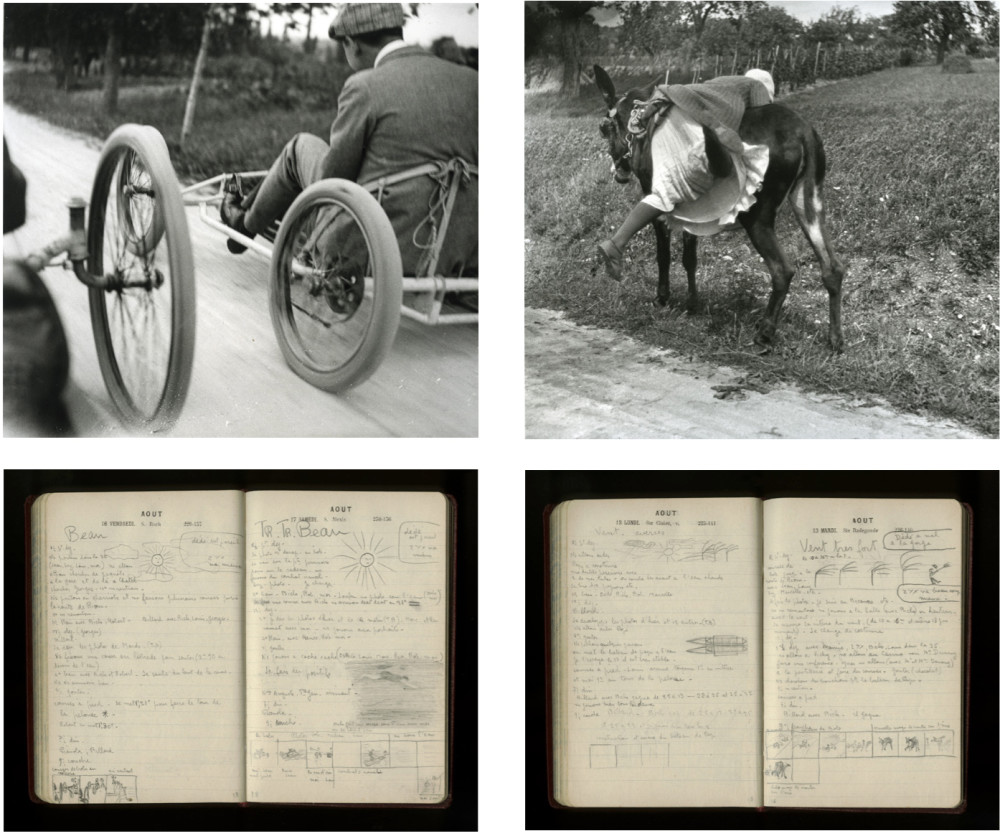

@Jacques Henri Lartigue(Top Left: George Boucard During the Race 1911; Top Right: Marcelle, Rouzat, August 1912; Bottom Left & Right: Pages from Lartigue's Diary)

@Jacques Henri Lartigue(Top Left: George Boucard During the Race 1911; Top Right: Marcelle, Rouzat, August 1912; Bottom Left & Right: Pages from Lartigue's Diary)

Lartigue’s art was temporally present in his life: feeding from it, and feeding back into it. Pushing forward in moments of enthusiasm, then receding solemnly into contemplation. Lartigue obsessively translated every detail of his life into tangible art, a compulsion exemplified not only in his photographs, but also in the diaries he kept consistently from an early age. Each diary entry begins with Lartigue grading his day on a scale of Beau, Très Beau, and Très Très Beau. Lartigue’s upbringing, which was privileged, no doubt influenced this unerring optimism, but it is much more nuanced than naivité. His optimism was a source of honesty, rather than delusion. It was a symptom of his sensitivity to life’s transitive nature. Everything moves, passes, changes; nothing, after all, is ever that serious.

©Jacques Henri Lartigue(The Day of the Drags, going to the Races at Auteuil, 23 June 1911)

©Jacques Henri Lartigue(The Day of the Drags, going to the Races at Auteuil, 23 June 1911)

©Jacques Henri Lartigue(The Road of Gaillon, 1912)

©Jacques Henri Lartigue(The Road of Gaillon, 1912)

For most of his life, Lartigue did not consider himself a professional photographer. His career as pho- tographer did not begin until 1963, after he had been taking pictures for 62 years, when his works were shown in the Museum of Modern Art. His legacy was established in part with help from his friend and admirer, Richard Avedon, who collaborated with Lartigue on the first book of his work. That his work never saw the--often corrupting--light of the art world during his most prolific years is the reason he was able to preserve their personal aspect. Behind each photograph is a simple, childlike excitement; each outing with his camera seemed a grand adventure. By creating a personal, diaristic body-of-work, Lartigue demonstrated how one can find the limitlessness within the limited, the infinite in the par- ticular. By exploring the borders of his experience, he created a universe of images that are as close as images can get to the fluid movement of life.

By Conor O'brien

Courtesy of Ministère de la Culture - France

Please check more about the artist at www.lartigue.org