Above Portrait by Andrea Blanch Andrea Blanch: Where have you recently shown your work?

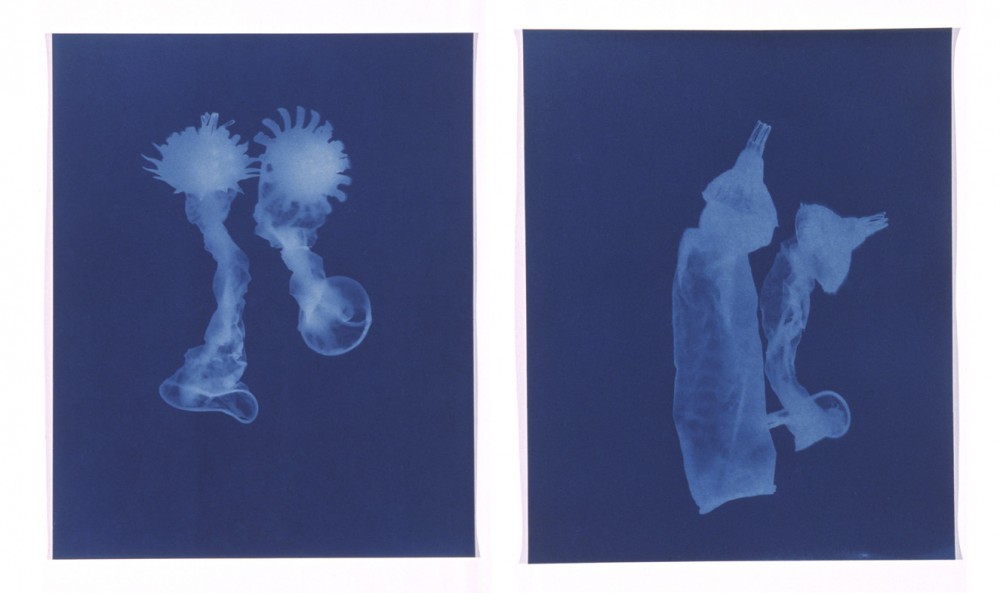

Wendy Small: Recently, I’ve shown in Williamsburg with Schroeder Romero, then in Chelsea with Morgan Lehman. I just finished the AIPAD photo fair and Paris LA with Von Lintel Gallery in Los Angeles. I have been working hard for years. I’m realizing that when I make a body of work that I like, it does get shown. Do you generally stick with photograms? I went to school for painting, and then I was an assistant to Terry Winters for ten years. I always thought I’d be a painter. I thought that I’d make large thickly painted, full arm stroke paintings forever. Then, when I started doing the photograms I almost didn’t notice that I had stopped painting. It was very unusual, because I was very fearful of not painting. You have an identity that’s set up in one medium. I was so excited by learning about photo papers and chemistry, that I didn’t feel the switch. That lasted for twelve years until recently when I started playing around with paint again. I can predict that my photo- grams will start to absorb my painting again, and now I have started painting with the photo chemicals. Can you explain to our readers who may not be familiar with photograms what they are and how you go about doing them? Photograming is a photo technique that uses light, an object, and photo paper. Prior to digital photography a negative was projected onto photo paper. Photograms use an actual object instead of a negative. You place the object directly onto photo paper and then expose the paper with light. The object will leave a “ghost image” or tracing. It’s direct. The different transparencies, translucencies, or opacities of the objects allow you to play with tone. Each photogram is unique. In Morning Glory, why did you use the condoms? They look like sea anemones. I became hyper-alert to transparent objects in the world. Everywhere I went I collected transparent objects, and people started saving things for me. I found those condoms in the back of the store Ricky’s, and they had these beautiful flower color tips. I was doing black and white work then, and they reminded me of Blossfeldt’s plant prints.

Could you tell us more about Blossfeldt?

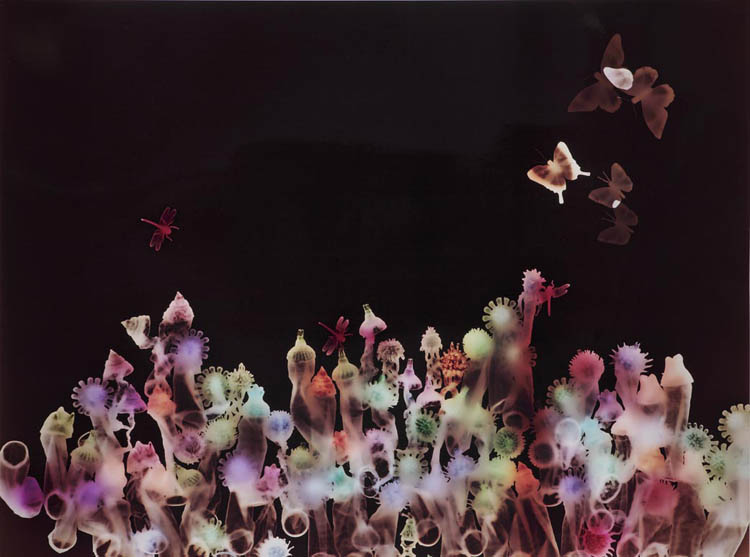

Blossfeldt was a German photographer who did a huge series of close up plant forms. They were more of a scientific investigation, but they were magnificently beautiful. I could arrange these condoms with these plant tips to mimic his plant studies, and that became very funny to me. Then they just grew. I often start testing things out in black and white. If the idea sticks for a long enough time or it becomes an expansive idea, sometimes it moves to color, sometimes it gets bigger in black and white, sometimes it’s a lasting series that I work with for a long time. The condoms called for large color. I was doing other color work and understanding more about color then, so I thought these could really become a beautiful garden.

Why did you use the butterflies?

Just to sort of reinforce the garden feeling. Those gardens were a very celebratory moment of condom use. We were in a lot of sexual fear for years. I started making them in about 2002. I grew up in the ‘70s and ‘80s when sex wasn’t scary. Then it became fatal. I thought the condoms could be celebratory. I thought, ‘We can get there. We can still have sex, we can celebrate it and we can be safe.’ It made me feel better on many different levels, and Morning Glory was part of that celebration. Morning Glory is a flower, so it worked for me on that level along with other various connections that I don’t usually mention.

Could you tell us about the spirals and the endless detail in your circular prints?

Those photograms that I call Micro Managed are an attempt to organize a whirling, relentless amount of clutter and details. I collect all that clutter and attempt to arrange it all in an almost symmetrical form. I had just become a mother when I started them, I was working full time, and making photograms at night in a community dark room down on Broadway and White Street. I could not believe the amount of details and stuff I was juggling (as was everyone else I met trying to work, make art and raise children). It is a slow and peaceful process to make those photograms, much like lace making; very connected to women who are holding together a lot of disparate parts.

Did you take any courses in photography?

No, I hated photography.

You hated it? Why did you hate it?

It was taught as a street photography class. You had to go out and find things to photograph. I really like working in a studio. I like having my own room. Now, I’m very attached to Instagram, I click pictures all the time, but there is something more tactile about what I prefer to do. I like the wetness of the developing, the fumes; I like rinsing the paper. I like to feel much more immersed in a project.

So if you didn’t like photography, how did you get to photograms?

I actually had done sculptures that were transparent. I started nursing school, and it was like a whole new visual set of things, so I started making sculptures out of objects I was finding in the hospital. There was a little transparent medicine cup that I really found to be quite beautiful, and I started doing all these little sculptures out of that medicine cup, called Medication Errors. Then it grew into wanting to join those medicine cups, and they were very difficult to attach to each other. It seemed the way to hold them all together was to photograph them, and I was not a photographer. I enlisted as many friends as I could to take these pictures for me, but then I started running with it and I couldn’t keep asking other people for help. One of the photographers was a friend of mine, Chris Gallo, and he suggested photogramming. There was a darkroom in the school that I worked at, and I just started with these small medicine cups, and those were my first photograms. For a while I was limited to this concept of using material that were involved in medicine, and then I busted out of that. Then it was just anything that was transparent.

What’s the largest print you could get from photogramming?

That depends on the darkroom that you’re working in. The largest that I’ve ever done were probably 50 by 60. It’s unmanageable after that; there are just too many objects. In the color darkroom you are in pitch black, so unless you’re really setting that up on a piece of plexiglass, you would be doing that in the dark. The bird photograms I did in the complete dark, moving around the grasses and the birds with my eyes closed. It almost gives you a better sense of what’s going on. It is weird, because if your eyes are open you really feel blinded, but if you close your eyes it’s very tactile, touching everything and arranging it. In the condom work I put them on plexi, because otherwise it would have been very hard.

Several of your series evoke William Morris’s 17th century textile designs, Victorian white boxes, and lace decoration. Is this something you look to for inspiration? Have you ever thought about doing wallpaper or working with textiles?

I was in a show once at Morgan Lehman in Connecticut that Lisa Marks curated, and she made a reference to French, Victorian wallpapers. I did look into wallpapering once, and there is a company that does artist wallpapers, but it’s by invite. You can’t just call them and say I want to do that. I do think that they would be beautiful as murals. Frish Brandt in San Francisco once sent me a very beautiful cyanotype process that people were using for ceramic tiling. I thought about that also. You know, you can never get all your work done. If you worked around the clock you couldn’t get all your work done. I’m doing what I can manage.

Where did you go to school?

I went to SVA. I had a very romantic sense of being an artist that I don’t know if people still have today. I didn’t go to art school at first; I had a wonderful painting teacher. It’s funny because in high school he was my high school painting teacher we took a pleasure course. He actually taught a course called Pleasure. So pleasure was always so connected to art for me. We did things like any combination of chocolate and coffee, we went mushroom picking, we read the Whiteness of the Whale chapter in Moby Dick, and we discussed what was the most pleasurable to us. This is when things started becom- ing obvious to me about becoming an artist. His name was Peter Leventhal, and he seemed a pure pleasure seeker. He taught that class in ’79, and we had buttered rolls with bagels, things that he loved and was tempted by, I guess. I always thought that was mixed in with art.

I travelled to Greece, Italy and Paris. I lived in Paris and he would send me letters about where to buy brushes and interesting walks to take. I was out in the world romanticizing a way to live that was incredibly tempting and pleasurable. It was all so different than my daughter’s experience at art school right now, where if she doesn’t take these computer courses, she loses traction in a major. I never even saw a computer. It just was a completely different experience. Then after about two years I was in Greece at the time—I did start realizing that there were some hard-core skills that I didn’t have. So I came back to New York to start learning.

This issue is about temptation. What tempts you?

I am incredibly tempted by almost everything. I think I move through the world propelled by temptation, desire, and curiosity. The problem is that sometimes it’s somewhat gluttonous, and I have to rein that in. Desire can get dangerous. In art, I am seduced by a lush surface. I think that’s why I photogram over photograph. I can play with the surface more; I can do lush, more oozing kind of references. I think in a way I have used photograms to almost curb the intensity of that temptation, where paint is sort of an endless play with surface. The photograms gave me parameters to work in, which I need because I could really whirl and go only into impulse.

Photo Series: Wendy Small. Morning Glory 4:25am. Courtesy of the artist and Von Lintel Gallery, Los Angeles