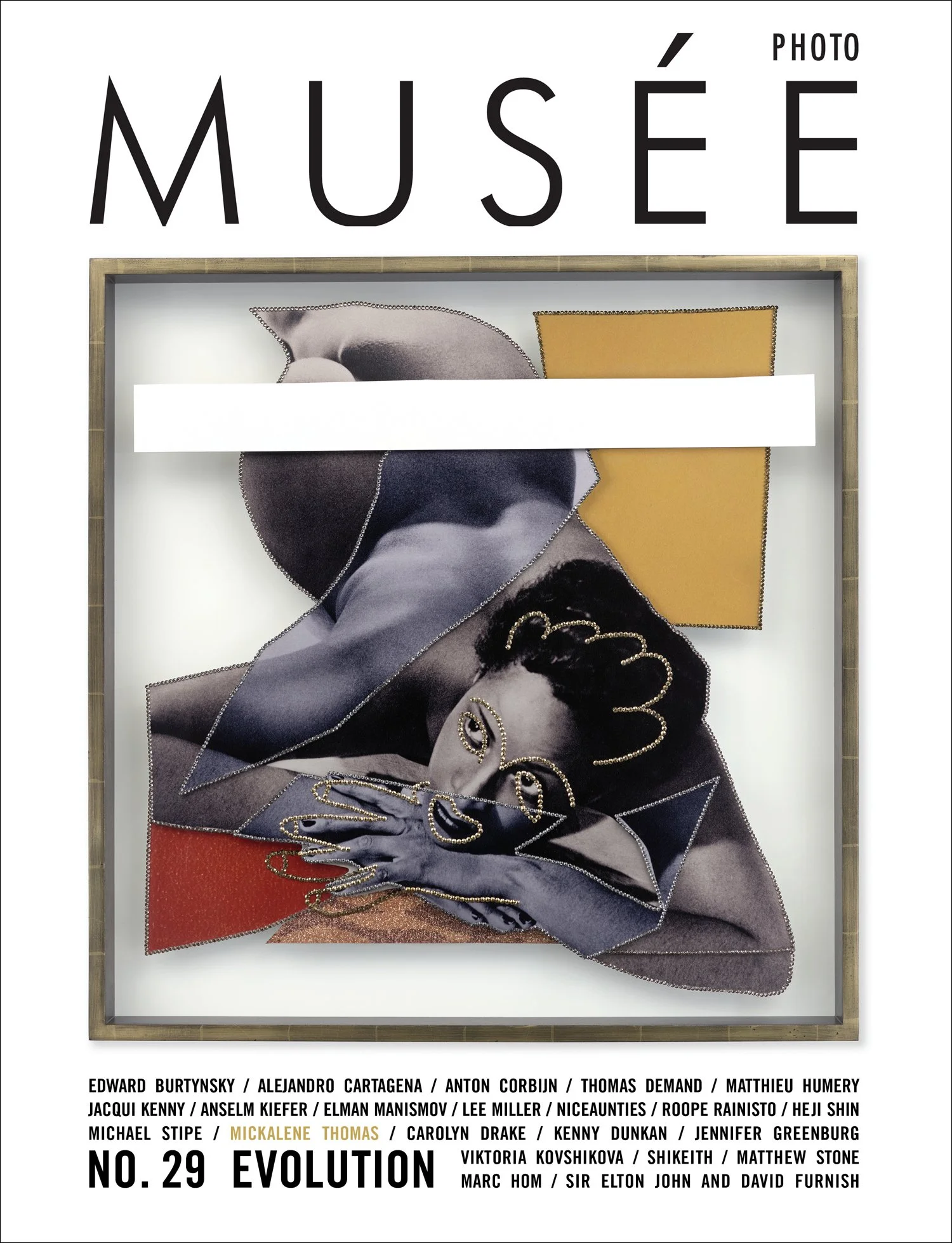

Lyle Ashton Harris: Our First and Last Love

Lyle Ashton Harris, Billie Dreaming in Blue, 2021. Dye sublimation print on aluminum. Edition 2 of 5. © Lyle Ashton Harris. Image courtesy of the artist and Salon 94, New York.

Written by: Edwin L. Harmon IV (Luz)

Luz: What does Pride mean to you?

Lyle: Historically Pride is an opportunity for people to come together to celebrate their queerness encompassing their multiple identities. Especially in New York, it’s amazing to see such a range of different people and multiple generations being out together. While I don’t frequently attend the actual parade anymore, it’s such a great way to visibly come together and foster community. It’s also important to reflect on the origin and history of Pride given the recent expansion of corporate sponsorship for these large public events, which doesn’t appeal to me as much as the alternative parades that take place throughout New York City’s boroughs—I’m much more drawn to the energy of those local neighborhood expressions of Pride. But with so much going on across the world right now, we also need to remain especially vigilant on how that’s impacting queer communities globally.

Luz: With identity and self-acceptance being a common subject in your work, did you always feel comfortable exploring it so openly?

Lyle Ashton Harris. Photographed by: John Edmonds.

Lyle: Whether you’re an artist or an activist—or both—it’s always about expanding capacity. Art has afforded me (and others) the opportunity to creatively express our lived experiences, to record that we were here, for example, by documenting the complexities around intimacy and desire. I find it sobering to reflect on all that’s unfolded since same sex marriage was legalized in the U.S. almost a decade ago. Given the resurgence of homophobia globally and the excess of reactionary anti-trans legislation that has been emerging across the U.S., we find ourselves living in increasingly complicated times. It remains to be seen how national Pride organizations will productively engage with these challenges, but I suspect alternative communities may serve as wellsprings for expressions of Pride that can give voice to our contemporary complexities. In my life and the worlds I inhabit, queer embodiment isn’t limited to the month of June—the inspirational energy of Pride exists year round!

““I think it’s important to understand that my work is not so much about trying to unpack identity as it is about relationally exploring my positionality to what has gone before and to what is unfolding in our present day lives, as a way to imagine a future to come.””

Luz: At the Queens Museum’s gala celebrating the opening of your solo exhibition, one of the presenters stated that, “To Lyle, naming is an action. A statement. A response.” What was the action and response that prompted naming the show “Our first and last love…”?

Lyle: Well, how do you interpret the exhibition’s title?

Luz: I interpret it as naming the importance of self-love, which reminds me of the saying, “I came into this world alone and I’ll die alone.” We are our own first and last love.

Lyle: I first came across the phrase “Our first and last love is . . . Self-Love” in the early 1990s while visiting my friend Tommy Gear in Seattle around the time his mother passed away. We were eating Chinese food near Pike Place Market and I received that message in my fortune cookie. I kept that fortune with me and later pasted it in my journal—I’m an avid journal keeper. A few years later in 1993, Creative Time presented the 42nd Street Art Project, which ran from July 1993 through March 1994 near Times Square in New York, and featured commissioned site-specific public artworks by two dozen artists including Karen Finley, Jenny Holzer, Glenn Ligon, Tibor Kalman, John Ahearn and Rigoberto Torres, among others as well as myself. I had been thinking about the use of language and text in artworks at the time, so I thought it would be interesting to deploy that fortune cookie message in the form of a neon sign that would be engaging for pedestrians walking around Times Square. Regarding the quote, I think naming that can be an act of care for oneself, given the idea that I—we, the collective—find ourselves constantly working through and actively affirming that there’s a certain labor entailed in the process of loving oneself. Nothing is stationary, everyone is constantly having to reassess and go deeper within themselves.

Luz: Is the sign featured in Queens Museum the same one that was featured displayed in Times Square?

Installation view, "Lyle Ashton Harris: Our first and last love". Photo credit: Hai Zhang.

Lyle: Yes, it’s actually the original 1993 neon artwork that was presented by Creative Time in the 42nd Street Art Project!

Luz: I admire how you continuously reference your own past works, especially in the Shadow Works series, photographing prints and other work you’ve made. How does it feel to be able to reference your previous works when making new ones? Is there power in that?

Lyle: What do you think?

Luz: Well I think it’s pretty iconic. You have to produce a certain amount with a certain level of intention to be able to do that effectively in your creative practice. So I observe that within your work and truly admire your ability to do that. I see that in your work and truly admire your ability to do that.

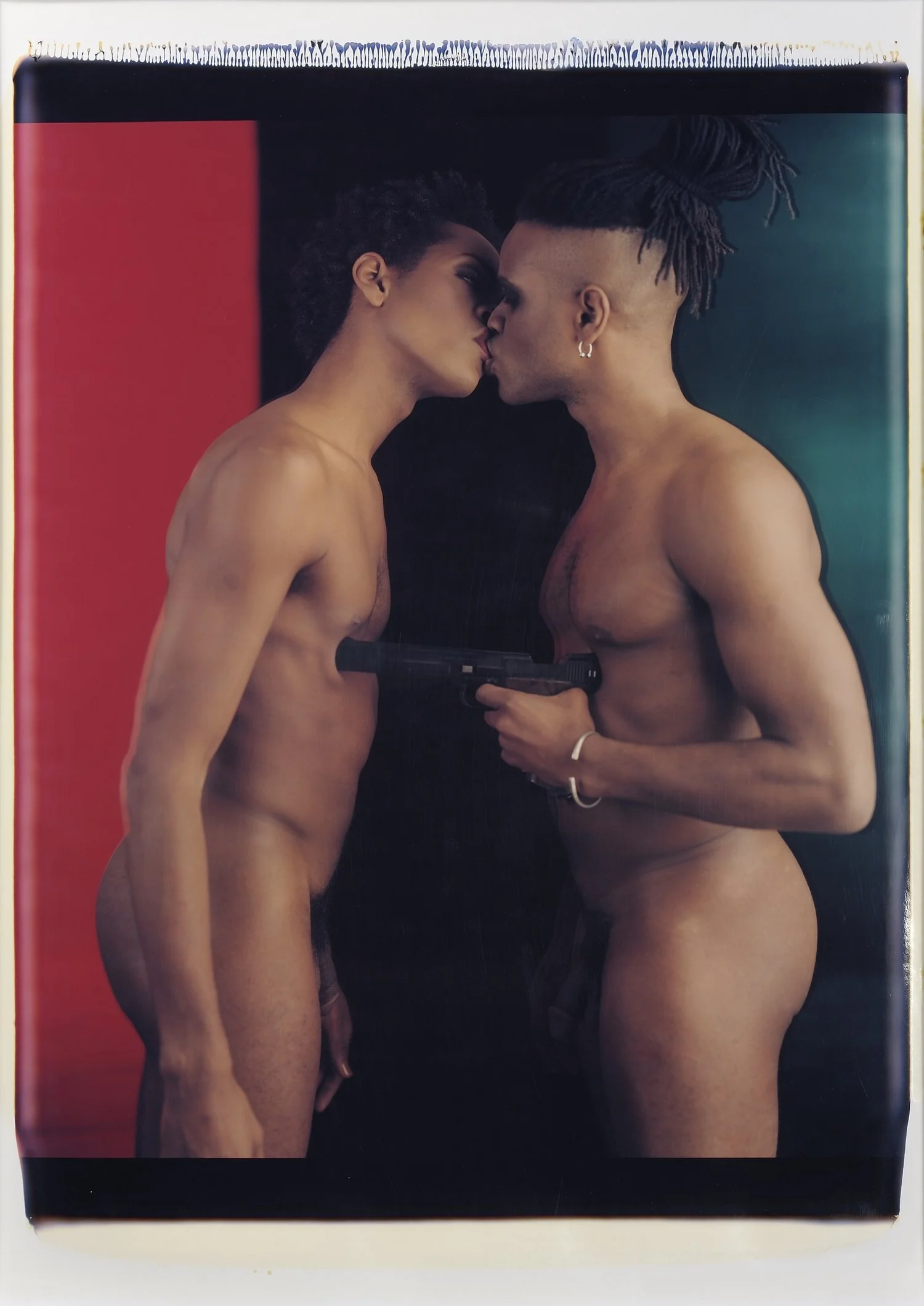

Lyle: I appreciate that, but I think it’s ultimately less about referencing the self per se—I am not an island! My work is informed by and informs the culture and community that I inhabit. Community is plural and identity is not stagnant; both participate in a fluid process of becoming. Another way to think about it would be exploring one’s experience of self as a vessel with which to reflect on what’s happening in the wider culture, producing artworks whose grounding references evoke the specific moment in which they emerged while illuminating viewers experiences of the present. That’s what many artists are called to do—I learned much from Toni Morrison’s musings on the role of artists in using our creative gifts to somehow lay bare the complexities and often contradictory aspects of the lives that we live. At my recent Queens Museum exhibition opening I was struck by the interest and questions generated by the collaborative large-format Polaroid that portrays my brother and me sharing a kiss [Brotherhood, Crossroads and Etcetera #2, 1994].

Lyle Ashton Harris, Brotherhood, “Crossroads and Etcetera #2” [in collaboration with Thomas Allen Harris], 1994.

Polaroid 2’H x 1’8”W (sheet). 2’11.5”H x 2’2.5”W x 2.5”D (framed)

©Lyle Ashton Harris. Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University; Gift of Blake Byrne

It was almost as if that photograph was being encountered for the first time. In a recent conversation with Ryan McGinley for Interview magazine, I recalled how triggered people were upon seeing that photograph when it was initially exhibited by Jack Tilton in New York thirty years ago. The continuing impact of that work speaks to the power of art. It’s not unlike when I encounter Adrian Piper’s work from the 1970s or a Caravaggio painting from centuries ago—such works can resonate as powerfully for us today as they did when they were first shown. During the COVID lockdown I re-watched Marlon Riggs’s landmark film Tongues Untied, and it never ceases to amaze me how it can elicit such a strong emotional response every time. It was particularly striking in midst of the recent pandemic that a film released almost four decades ago continues to be so potently relevant today and almost limitless in its nourishment!

Luz: I truly thank you for expanding upon that. Going back to the topic of self love, could you tell me a bit about your own self-love journey and how making work about it has helped you?

Lyle: That’s a pretty deep, personal question! What can you share about your own creative journey?

Luz: I think I am still on mine, and making work about myself as I continue to learn about myself validates those new discoveries. Being able to cement the way that I felt about myself or life at the time on to canvas or other materials helps me to process.

Lyle: What’s curious about one’s journey is that we have opportunities to drink from the wellsprings of those who’ve come before us. So I think it’s less about finding some kind of truth solely through my own self exploration, and then expressing that or making objects about it, but more about enriching our interconnections with others. Are you familiar with the work of filmmaker Marlon Riggs [1957-1994], who directed Tongues Untied, an experimental documentary exploring black queer community and desire? I was fortunate enough to have cultivated a close relationship with Marlon as well as other seminal artists and thinkers committed to bringing Black queer subjectivity to center stage both theoretically and creatively, not only to radically challenge heteronormativity but also to problematize the privileging of white queer bodies.

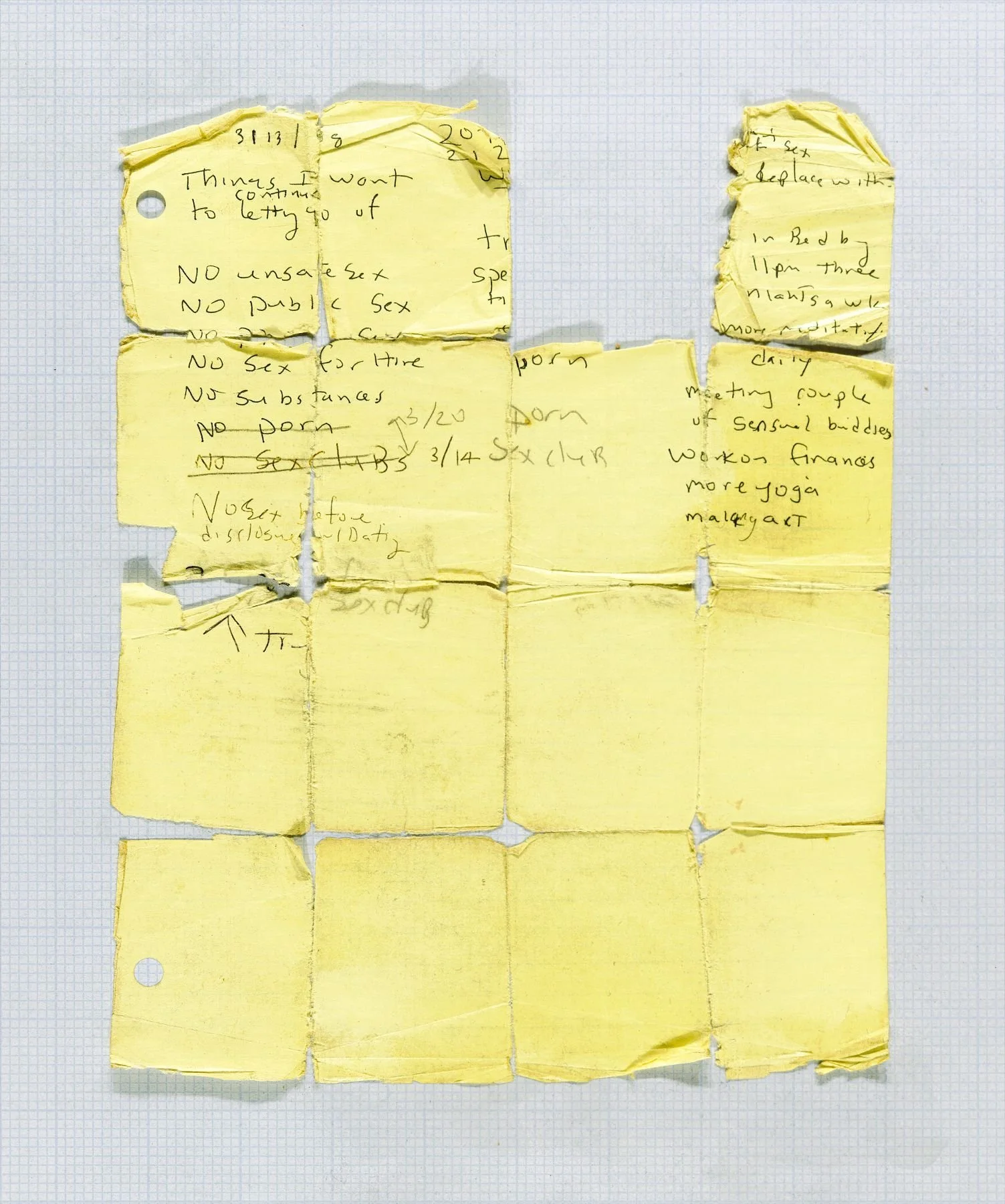

Lyle Ashton Harris, Untitled Images ©Lyle Ashton Harris.

Queer artists have produced historically foundational works, generating a legacy that artists today such as myself have imbibed to the benefit of younger artists like yourself and from which future generations can draw inspiration to carry forward. And though we each develop our own particular expressive language reflecting our individual life experiences, that will always be produced in relation to the wider context of the communities in which we participate. And the beauty of that is it’s no longer just an individual experience delimited by what you may somehow discover about yourself. Again, we are not islands, we are constantly in the throes of engaging with others and being affected by countless social forces.

Luz: We are not islands, love that. Do you feel like you have now taken on that role of putting black queer subjectivity center stage?

Lyle: It’s a pleasure to teach and mentor many undergraduate and graduate students at NYU and elsewhere, for several generations my work has attained a certain precedence, especially among younger artists who’ve come to understand the advantages and limitations of being hot one day and not the next, informed by an awareness of the art world’s complicity with the commodification of talent. Many artists today are more committed to creatively contributing to the greater culture than merely achieving market success.

Luz: I think your work is achieving that currently, putting black queer stories onto a larger platform. Particularly the piece Untitled (Yellow Grid), I felt very seen by that piece.

Lyle: Please say more

Luz: I’ve left a note like that to myself and I’m sure other young queer men have as well. Feels like you’re speaking from a very subversive part of our experience that not many would be brave enough to explore in such a public platform.

Lyle: And what experience would that be?

Luz: For example, the fact that you’re reminding yourself: “No sex with strangers. No sex for pay. No drugs.” etc. These demands you’ve written to yourself remind viewers that we still have to practice self-preservation and protect our bodies, especially in those openly sexual spaces that are commonplace in the queer community.

Lyle Ashton Harris, Untitled (Yellow Grid), 2014. Archival pigment on Kozo paper. AP 1, Edition of 3, 2APs.

©Lyle Ashton Harris. Image courtesy of the artist and Salon 94, New York

Lyle: I love that—and I really appreciate your vulnerability on the subject!

Luz: I appreciate your vulnerability throughout the entire exhibition! So regarding your Yellow Grid piece, I’d love to know more about the inspirations behind it and how you maneuver sexuality on that level?

Lyle: Actually, I think you nailed it. To your points, I think it’s ultimately about learning how to set boundaries and how to self-regulate, particularly now that there’s so much overstimulation through social media as well as pressure from contemporary consumerist culture. The actual source for Untitled (Yellow Grid) was a loose-leaf sheet of paper from my recovery journal after I became sober that I kept in my wallet over time and would add to here and there. It came out of a period about ten years ago of radical self-care as I was figuring out how to co-exist in the world with others while witnessing their lives being devastated by the choices they were making. I’ve been sober for twenty years now, and I’m grateful for having a second chance at life in so many ways. I think, in a way, this work registers my lived process of reflecting on the question, “How does one engage in self-care?” While this work is an expression of my very personal search for an answer, it strongly resonates with many people who’ve seen it—and not just those who are queer, Black, and male. The work also implicitly asks viewers to consider: What does it mean to actually name the complexities of the lives we live and acknowledge them publicly? As a public declaration, its vulnerability is apparent, but a degree of self-deprecating humor can also be inferred—by writing something, crossing it out, rewriting it, etcetera—which functions as a kind of “truth serum” disclosing the incessant self-negotiations common to us all. We each write our own lists of reminders or make resolutions that we keep to ourselves, so a lot of people find themselves spontaneously responding to that work because it unabashedly foregrounds our shared humanness. Though everyone tries the best they can, it can help to name certain things and just say, “Here’s what it is.” Particularly in the U.S., where there’s so much extremist judgment today, this gets reflected in internalized shame around the body, disease, aging, and death as well as the contradictions around sex phobia and its opposite, as reflected in pornographic culture. What I like about Untitled (Yellow Grid) is that it speaks directly to the fact that we don’t have to feel shame about engaging our human contradictions, and in so doing that may actually allow us to begin thinking differently and making different choices.

Luz: To see something so raw and true on a museum wall, down to the handwriting and crumpled texture– I couldn’t help but think of it as something I would have.

Lyle: I love that—I guess I didn’t realize how vulnerable displaying that piece in a museum might actually be! I think it inspires a sense of comfort in a way that opens people to connect with their own resonant experiences as well as the vulnerabilities around our complexities, our desires, our bodies, our insecurities, and our aspirations that we share with others—all of it!

Luz: How has your relationship to masculinity and the expectations that come with it affected your practice? Looking at your work and how you choose to photograph yourself, there’s a range of hardness and softness. In allowing yourself to be made up or hardened, I’m curious about your openness with exploring that range.

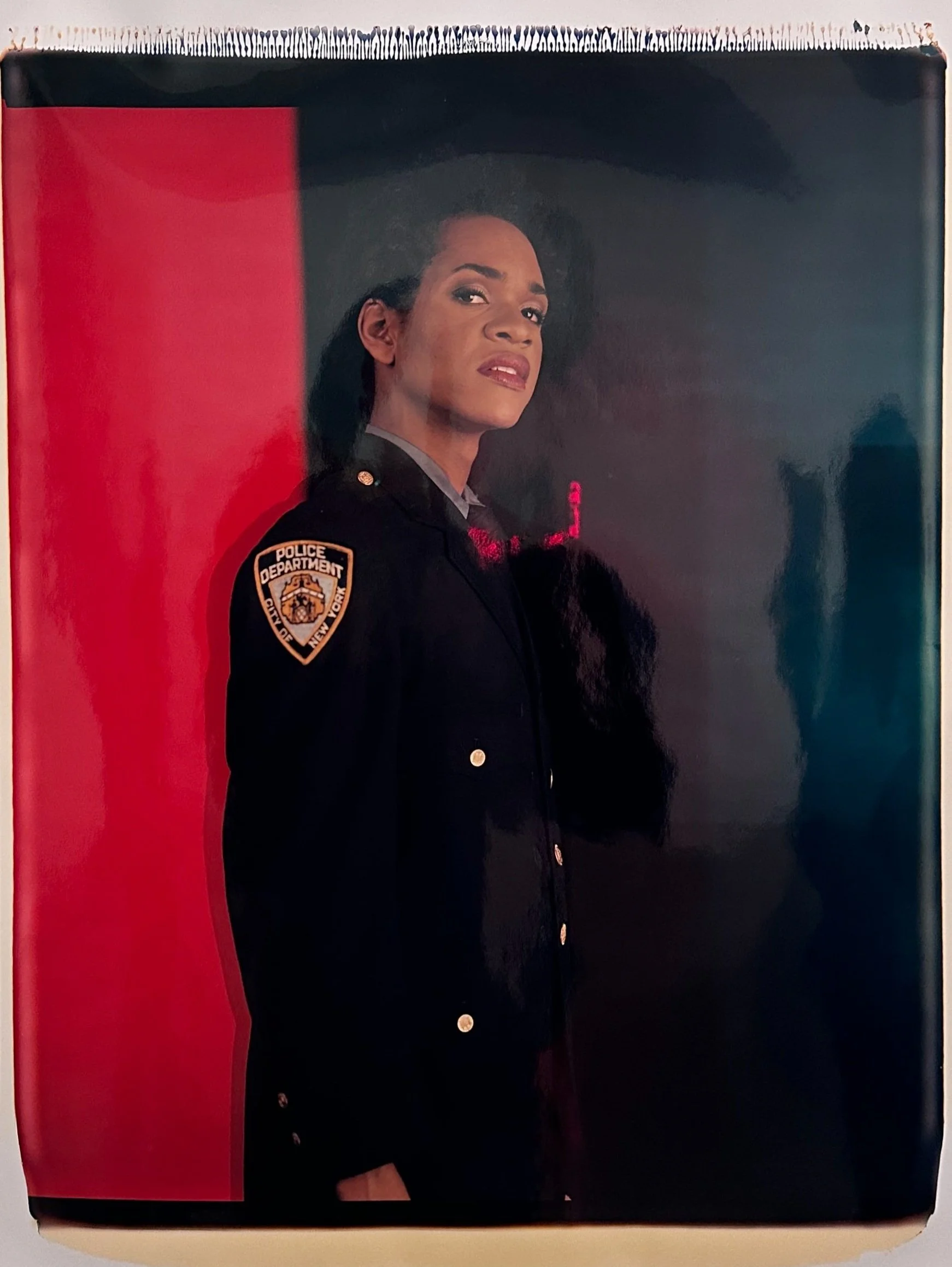

Lyle Ashton Harris, “Saint Michael Stewart [1994]”.

Polaroid 2’H x 1’8”W (sheet). 2’11.5”H x 2’2.5”W x 2.5”D (framed)

©Lyle Ashton Harris.Image courtesy of the artist.

Lyle: I think it exemplifies my embrace of fluidity in general, which is also reflected in my interest in exploring a range of expressive mediums. In my current exhibition at the Queens Museum, you’ll find my large-format Polaroid self-portrait titled “Saint Michael Stewart [1994]”, in which I donned make-up and a police uniform to memorialize the tragic loss of a young Black artist in 1983 at the hands of New York City’s transit police, which calls attention to the unequal treatment by the medical and justice systems that’s been experienced by BIPOC and queer people historically—it seems sadly prescient in terms of where we find ourselves today with increasing attacks on trans people and queer culture, a reactionary backlash to the expanded fluidity in identity and sexuality as well as the cultural shifts around femininity and masculinity. Recent legislation across African countries that criminalizes same-sex love (or even its public advocacy) as well as increasing homophobic repression in Russia and suppression of women’s rights in places dominated by radical Islamic ideologies attest to the increasing influence of these reactionary forces globally. That said, I think the current battles being waged against the greater acceptance of diverse sexual expressions and gender fluidity represent a backlash to the successful efforts over many decades by longstanding advocacy organizations and the many individuals who’ve actually put themselves personally on the line in the struggle for equality. This hard-won progress occurred on multiple political, legal and cultural fronts—in street actions that give visibility and voice to those otherwise marginalized, in academic institutions that honor dialogic exchange and value dissent, in supportive community spaces where a culture of respect and safety prevails—social change doesn’t just happen by attending corporate-sponsored gay Pride events! That’s why I’m continually acknowledging the seminal work of forerunners like bell hooks and Marlon Riggs, who live on through their writings and in films like Tongues Untied, as well as the other many of inspirational legacy figures who’ve laid the groundwork for today’s unabashedly out, Black, lesbian diva artists such as Mickalene Thomas, who was recently honored by the Gordon Parks Foundation.

Installation view, "Lyle Ashton Harris: Our first and last love". Photo credit: Hai Zhang.

Luz: There are definitely expectations regarding masculinity in the U.S. Thank you for your openness in regards to your own experience. What other feelings arise for you during Pride month?

Lyle: Pride is wonderful to celebrate in the summer month of June, but that should never eclipse or entail a forgetting of the many lives lost through the hard-fought battles of a shared struggle—from the deep influence of the civil rights movement of the 1950s-60s on the emergence of gay liberation movement in the 1960s-70s, to the impact of Black feminism on the development of Black gay male identity in the 1970s-80s, to the inspiration of AIDS activism in the 1980s-90s on the trans rights movement of the 21st century. The significance of being embodied—whether queer, gay, lesbian, bisexual, trans, intersex, pansexual, asexual, two-spirit, or questioning, etcetera—goes beyond the confines of a single month each year.