From Our Archives: PAUL MACHLISS: TAKE FIFTEEN

This interview was featured in issue No.20 - Motion

Award-winning editor Paul Machliss was nominated for an Oscar and won a Best Editing BAFTA (British Academy of Film and Television Arts) for last year’s tour de force car-chase heist movie, Baby Driver.

Edgar Wright’s exuberant action film was not only one of last year’s top-grossing movies, critics too adored its unbridled energy, tightly choreographed balletic fluidity, and an array of appealing performances—all set to a pulsing soundtrack drawn from an unlikely group of artists. Beck, T. Rex, Queen, Blur, Barry White, Sam and Dave, Martha and the Vandellas, and many others provided inspiration for Wright and his longtime editor, Machliss. While not a musical, the film felt like one. The result was stunning. Variety’s reviewer Peter Debruge called it “a blast, featuring wall-to-wall music and a surfeit of inspired ideas.” Australian-born, London-based Machliss explained how he and director Edgar Wright sidestepped traditional practice to invent a new way of creating movie magic.

BRUCE FELDMAN: With most movies, as an editor, you cut a film and a composer comes in and scores it. The way you made Baby Driver was exactly the opposite. What are the challenges involved with cutting a film with pre-recorded tracks? How do you make it all work with your hands tied behind your back?

PAUL MACHLISS: On first impression it may appear as just that. How do you have any kind of fluidity? The way you make it work is actually years of preparation. I was helping Edgar for four or five years before we shot a frame… he chose all the tracks because he had to write the script. He had all the tracks in mind, but we would see how the tracks would kind of crossfade and dovetail into each other. We would add sound effects and we’d just make these audio sequences to see how it would work.

But no, you cannot just turn up in Atlanta, plop a camera down in middle of the street, and think, “How are we going to manage this?” All those sequences were worked out intricately by spending several months cutting animatics, by working with CG (Computer-Generated) people, previs (previsualtion) people and, certainly, stunt people.

Sometimes to prepare, the stunt team would shoot and sometimes Edgar would shoot various stunts on his little camera, and so we had a cut of these particular sequences set to those tracks. We knew at that particular bar or that particular beat a certain bit of action had to happen. When you’re doing animatics or previsualtion, you can say “Okay, that car crashes in two seconds and then that happens and this happens.” You play it back and it all looks great. Of course, the laws of physics behave slightly differently in terms of what you want, and sometimes it might take seven seconds for a car to completely do its thing, you’ll cut it together to make the sequence work and later on we’ll add the score to work with your edit. But [here] the movie has determined that the crash will occur within that space and that space only. Of course I can’t invent an extra second and a half of music to fit in that area. I’m certainly tied to that. If there’s a thing where I do need a bit more space, I’ll allow myself a couple more seconds, but then 10 seconds from that point I need to be locked in there. That bit of action has to happen, and that can’t move. It’s fixed. So, the challenge really was to make it look creative, kinetic, interesting–not to make it look like it was planned to the hilt.

What we wanted to do was create a film that you could just watch if you didn’t want to know about the intricacy of it. You could just enjoy it as a good car chase film with some comedy, some drama and certainly lots of music. But if you wanted to, you could look at it and see how, like a mechanical clock, all these gears and things are clicking in together. One thing cannot work without several other things operating in a symbiotic fashion. In fact, that’s what we had to do when we were editing. We needed to have everything clicking in with everything else. I could not just put a shot in and go “that’s great!” You had to be aware of what was going on musically, sound effects-wise, rhythmically. It was predetermined, of course, but you still had your leeway. To actually achieve that final result is much harder than you’d expect. As you say, one hand tied behind the back.

BRUCE: Or maybe two?

PAUL: Or even two hands.

BRUCE: This process took a lot longer than normal?

PAUL: The big advantage and where we did a lot of the problem solving is that basically Edgar invited me to come and edit on set. That was the big plus with this feature. It’s something that he and I have done, ever since we did some reshoots on Scott Pilgrim where we first started doing a little bit of on-set editing. It kind of grew and grew over subsequent films, and finally on Baby Driver, he said “I think I’d like you there for the whole time, because that’s the only way we’ll know if this is going to work.” It would be terrible to get this all in the can, come back to London, start putting it together, and then realize that we just cannot make something work–something’s too long, too short, something doesn’t cut together properly. It’s critical that everything has its moment, doesn’t out-stay its welcome, and occurs where it’s due to occur. So to that end, I was actually a member of the filming crew.

Sometimes you have editors that go out and edit on the set but, more often than not, they’re editing the previous day’s rushes so that the director can keep an eye on how things are going. This was very much a case of me tethered to the video assist and Edgar going, “Right, we’ll do a take.” And he’d yell out, “Paul, how was it?” I’d probably just had about 20 seconds to go and say, “Fine, it’s good” or “No” or “Come have a look.” It was really edge-of-the-seat kind of stuff.

BRUCE: I take it that in planning these intricate shots you, as the editor, were much more involved than traditional editors. While these things have to work out to the director and choreographer’s satisfaction, ultimately you’re the one who has to make it all work. Your role is much greater than it otherwise would have been.

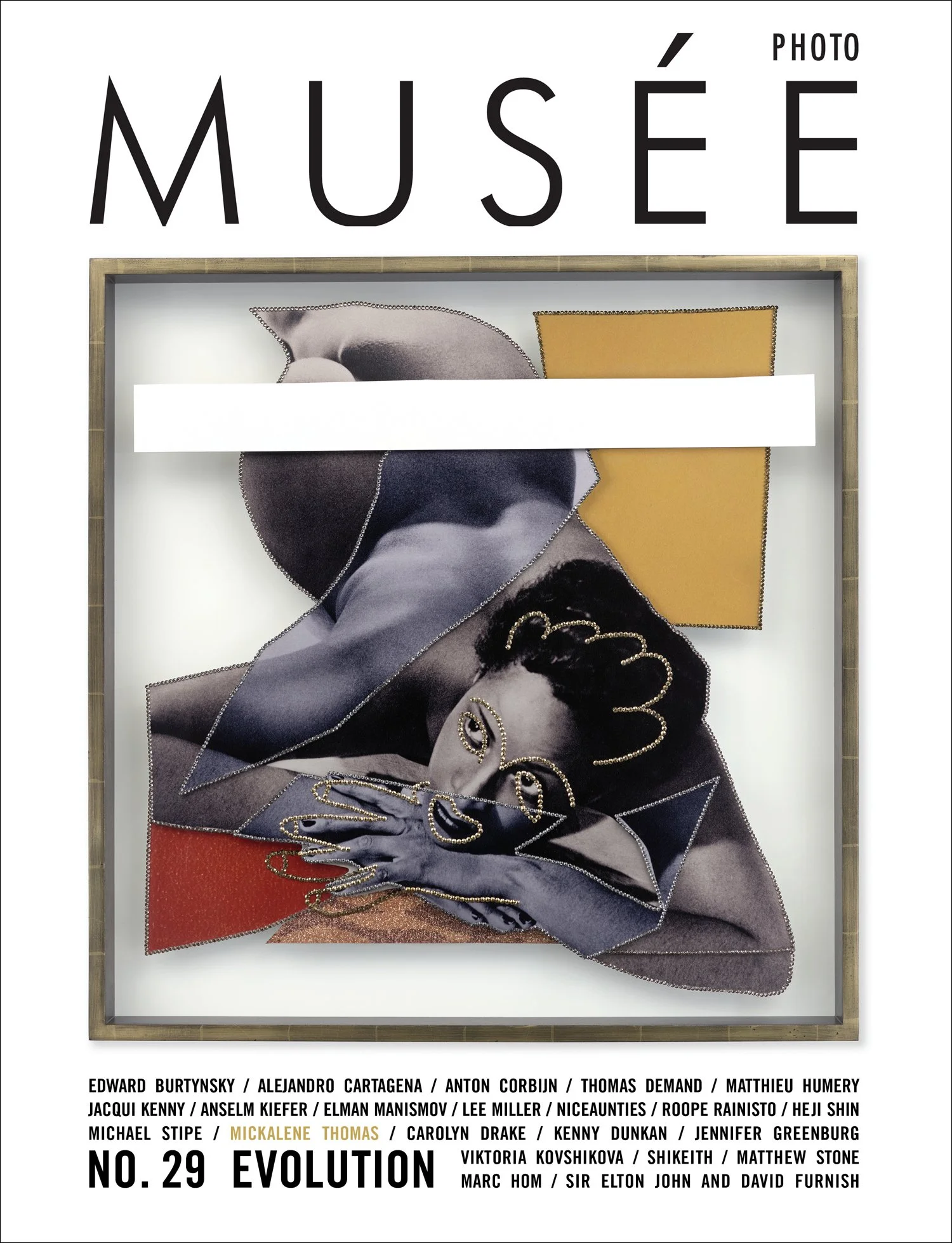

Read the rest of the interview in Musée Magazine's issue No.20 - Motion