From Our Archives: ALINA SZAPOCZNIKOW: CHEWED OUT

Alina Szapocznikow in her Malakoff studio, Malakoff, FR, Unknown photographer. 1972. All images © ADAGP, Paris., and courtesy the Estate of Alina Szapocznikow / Piotr Stanislawski / Loevenbruck, Paris / Hauser & Wirth

This essay was originally featured in ISSUE NO. 23 - CHOICES.

Written by Isabella Kazanecki

Photography is often associated with the ability to hold on to the ephemeral, fleeting moments of life. Whether those moments fill us with joy, grief, fear or safety, we still crave the ability to slow things down a bit, hold it all in our hands, and say, I’m a little closer to knowing what life looks like. Alina Szapocznikow is an artist who paused before permanence and made the choice to embrace ephemerality. In a statement about her oeuvre made shorty before her death in 1973, which was the result of a long battle with breast cancer, Szapocznikow said, “despite everything, I persist in trying to fix in resin the traces of our body: I am convinced that of all the manifestations of the ephemeral, the human body is the most vulnerable, the only source of all joy, all suffering, all truth.” Now, while she has literally fixed a number of objects in the compound, this, “mantra” was also applied across the board in every project she undertook. Her 1971 series, Photosculptures, is a collection in which Szapocznikow employed photography to “fix in resin the traces of our body,” in the most provocative means possible. These gelatin silver prints were Szapocznikow’s only venture into, “straightforward photography,” having previously worked only with found photographs in her series, Souvenirs. I believe that though this moment in her career may have been unconventional, it succeeded as a crucial deviation and one of the most interesting junctures.

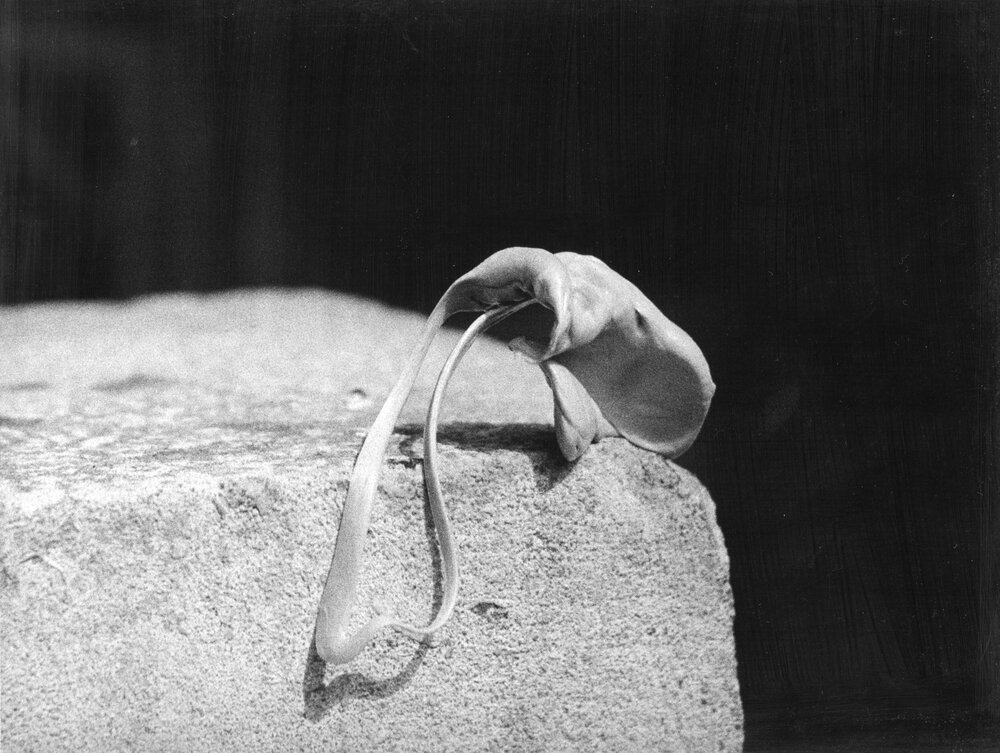

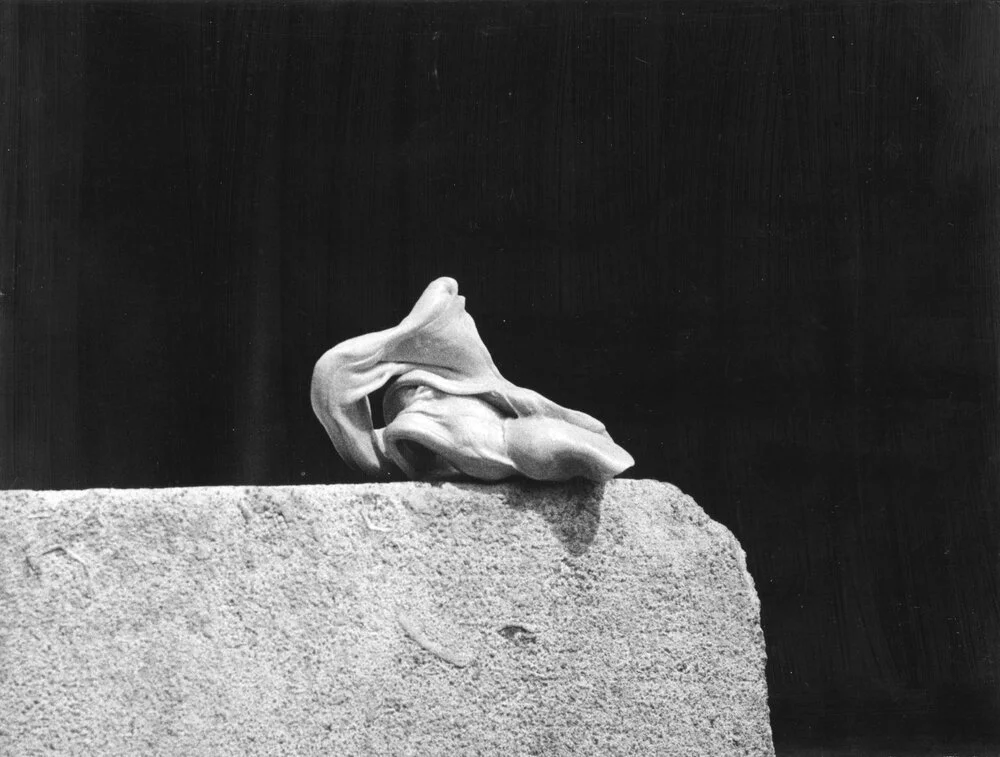

Szapocznikow settled on the idea to photograph chewed gum when she realized what an extraordinary number of original forms were occurring and disappearing immediately within her mouth. Roman Cieślewicz, photographer and husband to Szapocznikow, was on-site for the shoots and walked Alina through the printing process in the early stages. All gum was chewed by the artist herself and all negatives produced likewise. She is a sculptor by trade and saw this mode of improvisatory sculpting as an opportunity to mine both chance and intrinsic bodily capability in a new way. She chose photography as a means to document the sculptures, counting on the temporal nature of her chewing gum creations. In a typewritten statement, hung in the gallery at the beginning of the series, Alina says, “One has only to photograph and enlarge my creations in order to achieve a sculptural presence.” Photography, in this case, was the sculptor’s resin, her teeth stood in for casts, and her material was a commodity sold at newspaper stands. The shapes of the gum were on par with her previous sculpture aesthetics and took on abstract anatomical forms, further driving home the point that this project explored personhood and objecthood. Looking at the twenty pieces of chewing gum, I could imagine the artist—or myself—imitating each one and choreographing a kind of dance. Photosculptures reconceptualized sculpture and displayed a unique understanding of lived bodily experiences. Directly after the previous statement, Szapocznikow writes, “Chew well then. Look around you. Creation lies just between dreams and daily work,” which reminds me that a big part of Photosculptures—as well as the entirety of her oeuvre—was not just the serious meditations on, “the body” but play, humour, and spontaneity.

Read more of this essay in ISSUE NO. 23 - CHOICES.

View more of Alina’s work here.