From Our Archives: Andy Warhol: Master of the Instant

Andy Warhol, Self-Portrait in Fright Wig, 1986. All images courtesy of Jack Shainman Gallery © 2019 Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

““I told them I didn’t believe in art, that I believed in photography.””

For someone who took approximately 150,000 pictures in the last dozen years of his life, Andy Warhol is rarely remembered as a photographer. Though his iconic screenprints are clearly derived from photographs, his use of the medium seems secondary in larger conversation about his work. His childhood collection of glossy Hollywood publicity photos gets frequent mention as context for his love of celebrity, but their material nature ignored. Interest spread in 2007 and 2008 when the Warhol Foundation distributed 28,500 of his photographs to nearly two hundred universities across the United States, and yet only a few shows over the years have concentrated on his photography or tried to position it within the history of photography, most recently at the Jack Shainman Gallery in New York.

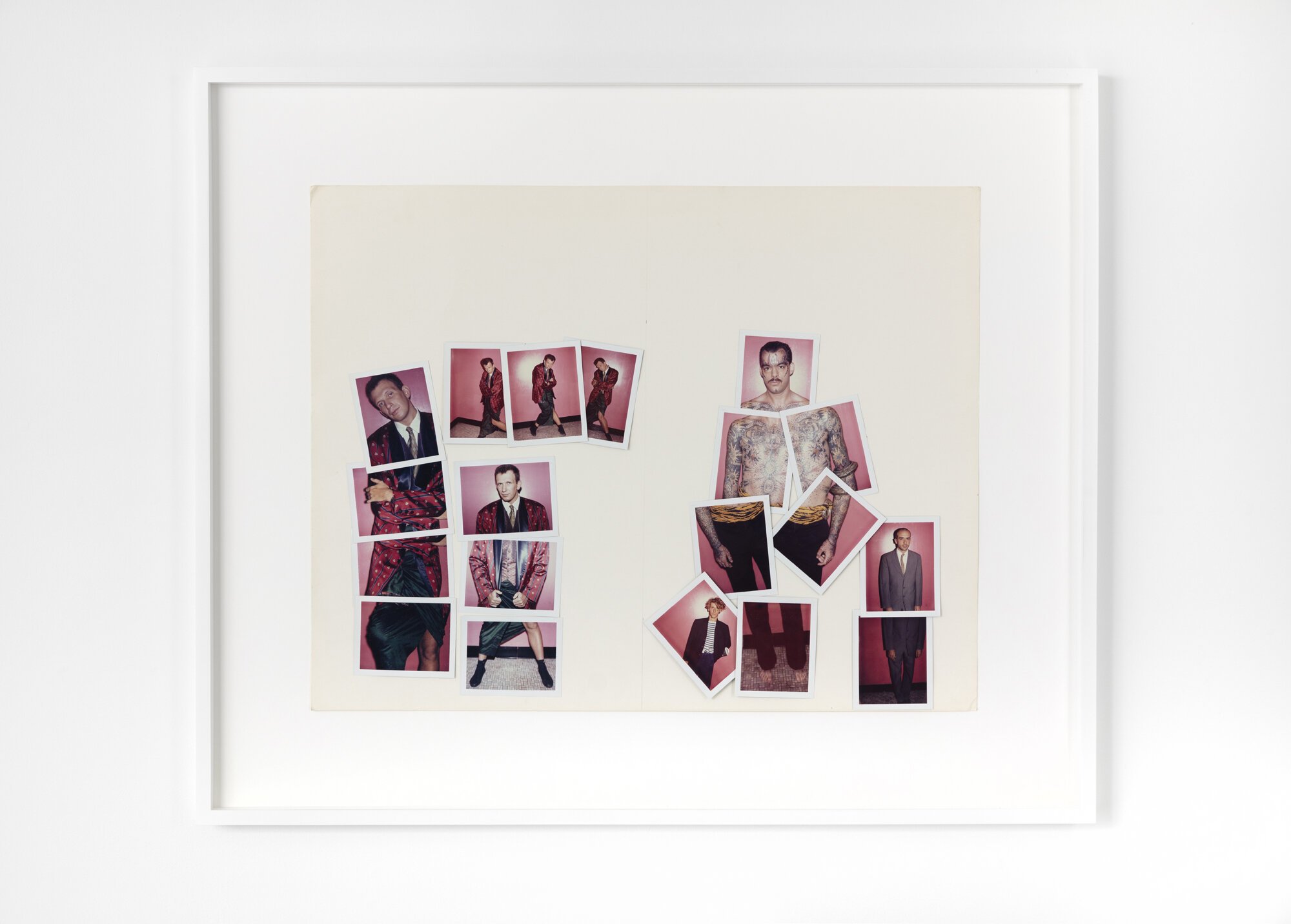

Andy Warhol, Jean Paul Gaultier, Francesco Clemente and Tattooed Man, 1984.

Warhol’s ubiquitous camera and tape recorder went everywhere he went, at all times of day and night. This appears to be another example of the ways in which Warhol foreshadowed the contemporary, with the constant presence of the camera phone capturing ordinary lives in all their glory and making celebrities truly ordinary.

Warhol was born in 1928, only three years after Anatol Josepho patented the Photomaton, a machine that popularized the instant photo by providing customers willing to pay a quarter with a strip of eight images delivered in eight minutes. Years later, Warhol would regularly send clients with quarters and instructions to photo booths to produce the images that would be the basis of his famous silkscreen portraits. Squished with friends in a photo booth, people become playful. The photo booth also provides the space for those who are alone to shed any self-consciousness that might arise when faced with a human photographer. Across the assorted photo booth images, sitters reveal campy silliness as much as they do tender self-reflection. The strip of images offers options, multiple strips ensure that one image will satisfy, and the immediacy eliminates any anxiety of waiting to see, hoping to find one pleasing image. It also conflates the high-class status of a commissioned self-portrait, with the cheap and trashy qualities of the automatic photo booth––a classic Warhol gesture.

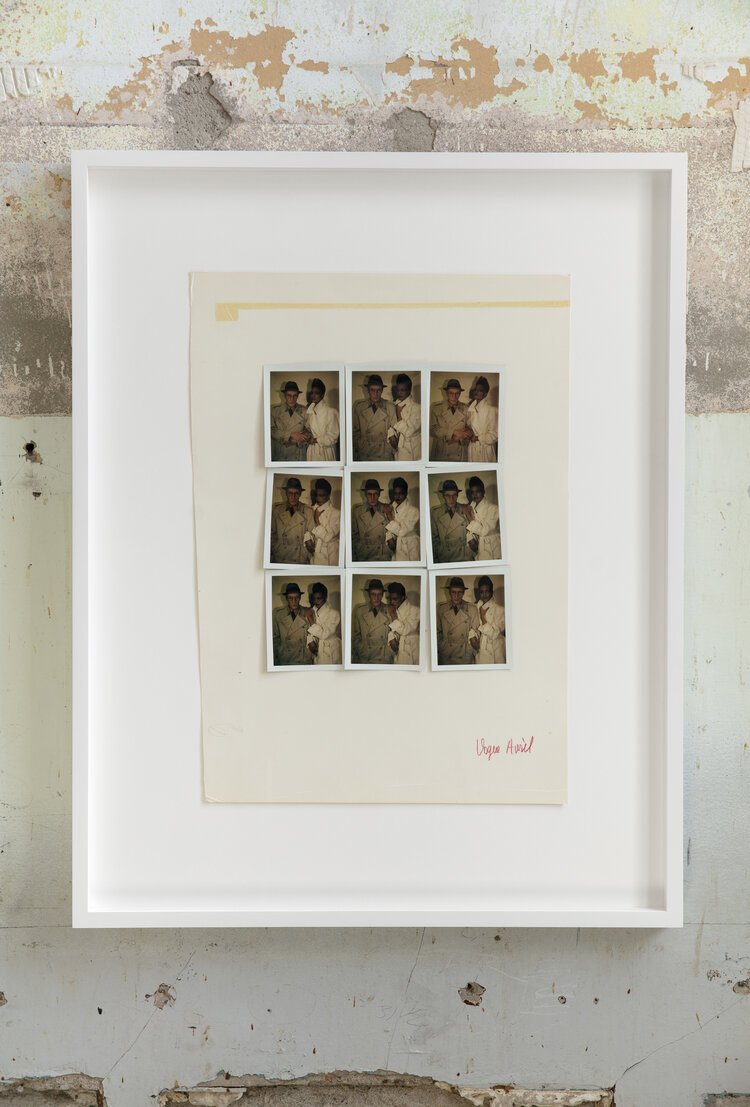

Andy Warhol, William Burroughs and Model for French Vogue, 1984

As many teenagers of his generation, Warhol had a Brownie camera and even created a dark room in the basement of his family home in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. This photography foundation was enhanced by his older brother’s employment hand coloring photographs at a photo processing business, which is where Warhol likely tinted his beloved, signed publicity shot of Shirley Temple. Warhol was not suited to the labor of developing photographs and shifted to automated and instant cameras. Beyond the celebrity film stills for his first screenprints, he embraced the photo booth, as well as a series of single-lens-reflex cameras, like the Chinon 35F-MA, the Olympus AF-1, or the Minox 35 for his production process. The Polaroid Big Shot and SX70, however, would be particularly significant.

Andy Warhol, Above: Table Setting, 1979.

The Polaroid Big Shot was only produced from 1971 to 1973. Working at a fixed focal length of forty-two inches, it was specifically designed for portraits. To identify the focus, photographers would do the “Big Shot Shuffle,” moving back and forth until the two images in the viewfinder united. This along with the simplicity of its single-speed mechanical shutter and the diffused light of its flash allowed absolutely anyone to procure well lit, quality images each time. It even provided a sixty second timer that guided enthusiastic users how long to wait before peeling apart the film. When Warhol took Polaroids of his sitters, he kept them all––no matter how much the commissioner might beg for one of them. He labeled them with a steel embossing stamp “©ANDY WARHOL” and catalogued them carefully in designated albums. These behaviors are not merely examples of his disposition towards accumulation, but emphasize an awareness of their relevance to his work. The Big Shot has retained its celebrity portrait status with numerous photographers using it for red carpet awards. In 2017, Rizzoli published Big Shots: Polaroids from the World of Hip Hop and Fashion, which consisted of moments captured by the tour manager Philip Leeds. When a representative from Polaroid introduced him to the SX70 in 1973, Warhol embraced its even greater portability and ease, eventually coming to own ten of them.

Find more of this interview in ISSUE NO. 23 - CHOICES :