Parallel Lines: Giada De Agostinis

© Xiaopeng Yuan

Federica Belli The language of photography is still among the most contemporary ones, despite the growing diffusion of other digital arts. Which forms of photography do you find particularly exciting in our time?

Giada De Agostinis Very challenging question. What I like involves certain ways to push the medium and the way we look at things. There is always space for the discovery of new practices through which artists challenge themselves and their techniques. It’s hard to names people as it somehow involves showing preferences, yet there are artists challenging the medium by reframing identities and histories, also just by looking closely at their own family histories. For example, Leonard Suryajaya, he pushes in the ways he constructs his staged photographs, and whenever I look at his work I can’t help but feel that I’ve never seen anything like that. It strikes me how such a complexity can directly lead to what the work is about. The magic happens particularly with artists who challenge the way we look at stories through different narratives or with the ones who may challenge just the common printing techniques. There are artists doing amazing work not only in terms of photographic research but also through painting and by exploring other words, like Jean-Vincent Simonet – who uses a printing technique I would have never thought about – or Maya Rochat. Other artists can be innovative while telling a simple story. We recently published a book by Gillian Laub, Family Matters, which is incredible in the way the photographer pictures her family through a gaze that could speak to so many people in this country. The way photography can be direct in conveying a message is just incredible. And also books like Photography is Magic – which was published by Aperture in 2015 – prove how whatever we look at is largely influenced by the viewer’s imagination, which plays a huge role in bringing out the magic of the world. Whatever we experience, we can always look at it in different ways. Photography remains an artist’s work, but we can always change the way we look at it as well. What matters is to remain curious.

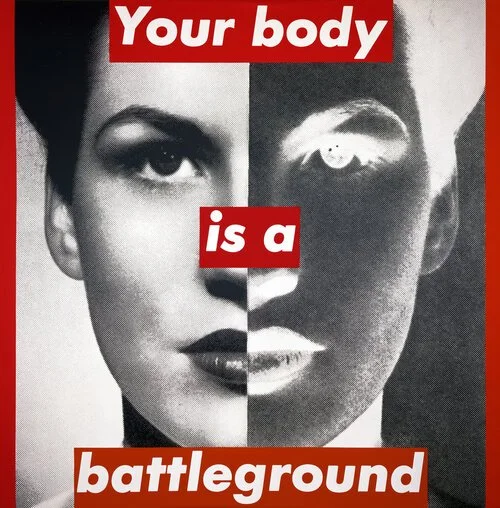

F.B. After all, the most exciting aspect to photography is that it pushes us to constantly reframe what we are confronted with and challenging our thoughts. The last edition of the PhotoVogue Festival in Milan, for instance, was centred around the role of photography in Reframing History. We feel like we have seen it all, yet have we also considered every perspective of what we have seen? And it becomes a political matter as well. In 2016, as right

wing politics were rising and extremism was becoming the norm on social media, you wrote an article about how the role of photographers adapted to the circumstances in terms of they represent the ideas of freedom and dignity. Can you elaborate your perspective on this theme?

© Carmen Winant

G.D.A. Yes, that article came out after Trump got elected, a period in which we witnessed a certain violence, also beyond visual communication online, touching our daily language as well. Of course, artists have tried to respond to that climate in different ways. It could be very overwhelming, as everything we experience now is filtered through these channels, yet it’s

interesting as we have never been exposed to such amounts of geographical exposure in terms of what we can see on social media. We witness protests and revolts from other countries, which are quite difficult to make sense of from afar. During the protest time, while many artists documented what was going on, collectives like For Freedoms have been particularly active in involving artists in a dialogue about democracy and how we are protecting it. It becomes very hard for individual artists to respond to such heavy circumstances. Some photographers have faced those issues in their work, often outside the social media sphere. One of the most interesting movements happening in the past years is how artists did fundraising with their work, in order to help grassroots organisations. And it still going on for other causes.

F.B. That is a theme I was not expecting we would touch, yet I am extremely glad we have. Such fundraising phenomenons have reinforced the intrinsic power of art to support communities and sustain beliefs, challenging power hierarchies.

And another way in which photography challenges our culture lies in the way it somehow refuses the idea of productivity. In our culture, it has undeniably become one of the most common units of measure for self-worth. Yet photography, just like other art forms, requires a slower approach to life. How are photographers reacting to such conflicting inputs?

G.D.A. An artist should never start out by thinking of producing for the market. The primary objective is generally self-expression and challenging the narrative, so getting entangled in the market requirements is quite risky. That is often the case with photographers who become very famous at a young age, who are constantly requested to produce more or are proposed multiple shootings. It becomes fundamental to protect oneself and to select what one does, depending on whether we are talking about artist projects or commercial works. And many photographers try to combine the two, by making a living out of one and expressing themselves through the other channel. It is very difficult to find a balance between the two. There are artists who work specifically on these topics of productivity and consumer culture. Think of Sara Cwynar, who is involved in exploring our consumer culture and our tendency to amass material and archive it all, without any expectation to ever go back to these loads of photographs and products. The whole idea of artists as producers and observers as consumers can get very overwhelming in itself. Ideally an artist should not be concerned about the pace of consumer society and productivity, yet they also need to make a living with their art. And such conflict poses a challenge, also in terms of conceiving projects and what the end results might be.

F.B. And at a young age, when photographers are mostly trying to figure out who they are professionally, one can only realise how such identity coincides with the who they aspire to be humanely and how they can measure their progress.

Talking about progress, the development of a photographer often involves, at a point, a photographic book – widely considered a milestone in the career of a photographer. However, sometimes the work is not mature enough yet, and at times it does not fit the book format at all. How can a photographer understand when the times are ready for a book?

G.D.A. This conception that the major point of success of an artist is publishing a book has been shifting. There is a growing volume of photo-books, with artists creating their own book at the beginning of a career as well – mostly due to the increasing accessibility of the medium.

Not all projects fit to become a book and not all of them would function as a book. The PhotoBook Review is a journal by Aperture dedicated to the consideration of the photobook (which will be incorporated into the magazine). It helps to understand how the photobook can be a means to look at your own work in a different way by simply sequencing the photographs and editing the series, or by confronting professionals in the field and getting feedback. The photographer gets a different sense of what the project is about and of the point they are at in the process of putting together a consistent story. It can only help – maybe also to understand that the project would not work in the book form. Most of the times, after all, growth comes from discussion with other people. And there is no way to build a photobook alone, there are the editors, designers, printers… it is such a collaborative process that it is just an added value for every part involved. And it cannot be rushed.

© Ming Smith

F.B. At times the process of imagining and realising a project can be quite individual, thus the successive phase of seeking feedback and seeing it laid out on paper for the first time comes as a pleasant consequence. At the same time, photographers tend to be quite reluctant to show their work until they somehow feel like it’s ready – and it never is – so being in some ways forced to collaborate as in the case of making a photo-book can encourage the discussion.

After all, being a photographer nowadays goes well beyond taking pictures, involving both a long process of research before the realisation of a project and its promotion once the work is completed. Regarding the latter, which means can photographers rely on to get their work to be seen?

G.D.A. There are a lot of channels, yet for most artists it is hard to communicate their work. In the online scenario we live in, it is fundamental to plan a strategy. Many photographers have a gallery or professionals around them who might help in promoting the work, but for many young photographers that is not the case. The first advisable step is sharing the work with the community at its initial stage. It helps to create a group of professionals who get familiar with the project and thus can follow along its development. Even though this approach might not show results immediately, it will probably reveal its usefulness in the following year. Also, though one might not get many replies to emails when reaching out, editors and publishers actually do look at messages and might go back to it after a long time when digging in their archives. Social media is another useful platform for professionals to follow the development of a series or to get a sneak peek into an artist’s practice. Another approach involves finding a publisher for one’s work in order to have it circulate more organically in institutions and events. Moreover, contests and prizes are fundamental to have one’s work seen: even though a series does not get selected, curators and judges become familiar with the work. And I know it takes a lot of time. And I know it does get frustrating. But it is fundamental to plan and allocate the necessary time for these activities. Sharing one’s work around often leads to the natural birth of a community of photographers who support and share it around: there is a lot of altruism and generosity in the community in that sense.