Feature: Ming Smith

Ming Smith, Amen Corner Sisters, Harlem, New York, 1976, from Ming Smith: An Aperture Monograph (Aperture/Documentary Arts, 2020) © Ming Smith, courtesy the artist and Aperture

By Sara Beck

Before she gained global recognition for her photographs, Ming Smith was a young girl living in Columbus, Ohio taking portraits of her kindergarten classmates with her mother’s Brownie camera and carefully watching her father develop negatives in his darkroom. Having often listened to her father’s discussions with his peers about the medium, she later came to realize that she disagreed with his philosophy, which struck her as sterile and overly technical. Upon leaving Ohio and graduating from Howard University in Washington, D.C., she took up dancing and modeling in New York before discovering, in 1972, the Kamoinge Workshop—an all-Black photography collective she credits with introducing her to a new concept of photography that holds artistic expression and emotionality at its core.

When looking over her life’s work, it is not at all surprising that Smith felt inspired by Kamoinge’s photographic method—movement and a sense of life are clearly central to her images. Arthur Jafa named a phenomenon present in a multitude of Smith’s photographs “the blur.” What he was referencing is often the result of an image captured in low light at a low shutter speed, giving the subject an ethereal, almost ghostly presence in the frame. Smith, perhaps drawing from her background in dance, has emphasized the importance of improvisation in making these technical choices, comparing her thought process to that of a jazz musician. Low light does not deter her from making a picture; Smith has never relied on visual perfection to capture a scene. In her eyes, the making of a great photograph is more related to the spirit of the image shining through, the imperfection and mystery which make something feel alive.

Ming Smith, West Indian Parade, Brooklyn, 1973, from Ming Smith: An Aperture Monograph (Aperture/Documentary Arts, 2020) © Ming Smith, courtesy the artist and Aperture

Light is not the only element of the medium with which Smith improvises—she frequently carries two cameras on her at once to allow herself the opportunity to shoot in either black and white or color depending on how a particular moment inspires her. Moreover, Smith asserts that color is present in her black and white work, too, as various shades of monochrome create as much intrigue as color. Statements such as this parallel the poeticism that is immediately recognizable in Smith’s images, revealing how the artist gives viewers glimpses into both the external world around her and her own internal universe.

Ming Smith, Sun Ra Space II, New York, 1978, from Ming Smith: An Aperture Monograph (Aperture, 2020/Documentary Arts, 2020) © Ming Smith, courtesy the artist and Aperture

Since her first exhibition at Cinandre, a New York City hair salon, her work has been shown at the Brooklyn Museum, the Tate Modern in London, and the Museum of Modern Art. In fact, Smith was the first African American woman photographer whose work was acquired for MoMA’s permanent collection. Despite this monumental achievement, she did not receive proper recognition for her work until it was long overdue. Years passed before she saw praise for her pioneering photographic representations, particularly of Black femininity and the richness of Black culture, and for tackling issues such as the gaze, erasure, and the struggle for survival. Her series entitled Invisible Man, drawing from Ralph Ellison’s novel, confronts the lack of recognition Black artists receive and the mixture of anger and yearning which result from this systemic problem.

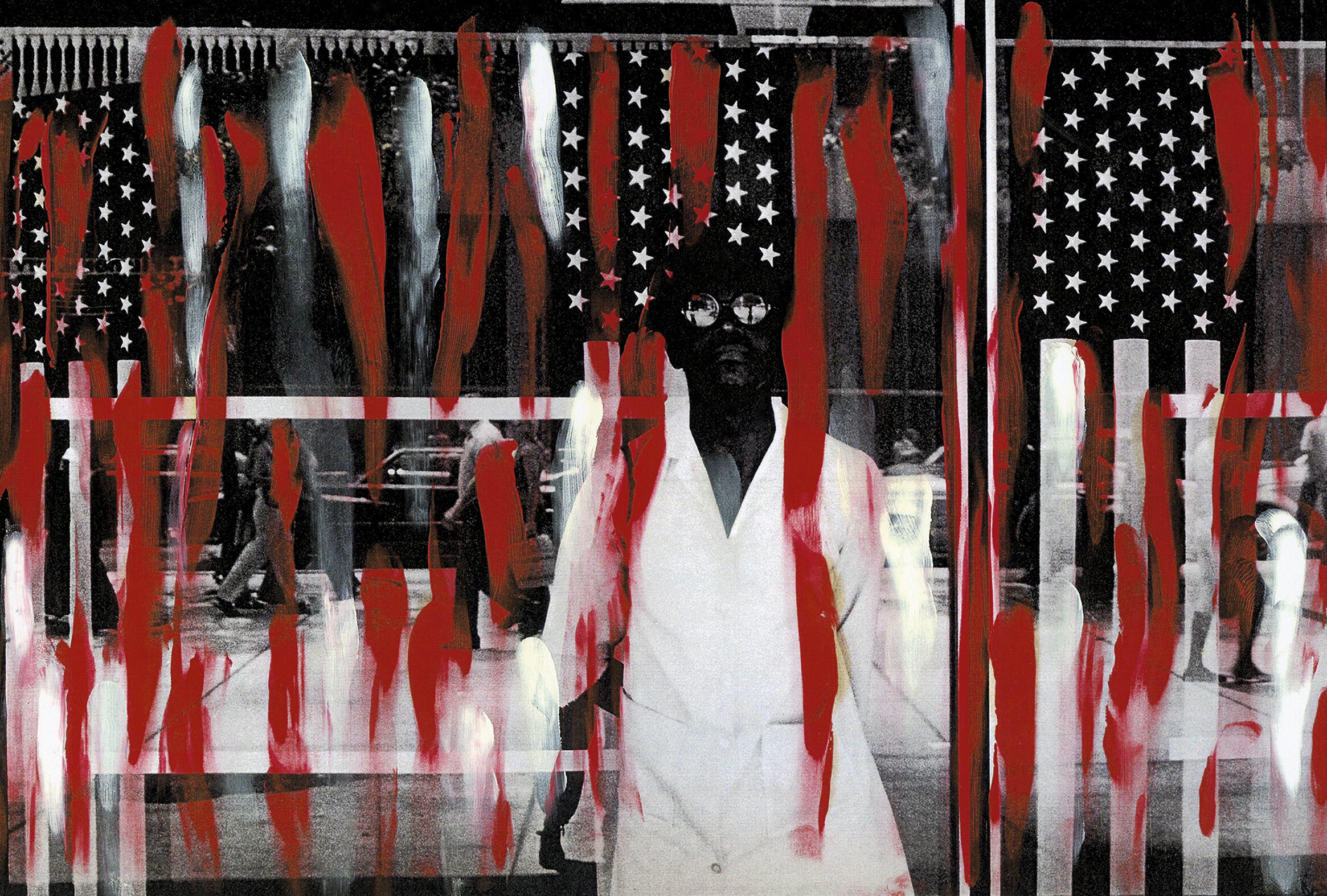

Ming Smith, America Seen through Stars and Stripes (Painted), New York, 1976, from Ming Smith: An Aperture Monograph (Aperture/Documentary Arts, 2020) © Ming Smith, courtesy the artist and Aperture

Most recently, Smith was honored with an Aperture book surveying her work. Evidently, her images strike as much of a chord with today’s audiences as they did when they were conceived. This undoubtedly speaks to her extraordinary artistry. Beyond this, though, Smith’s career path itself and the long delay she experienced in receiving due recognition is indicative of the fact that the issues she has fought to dismantle since the start of her career are still present, both at the surface and buried deeply underneath.