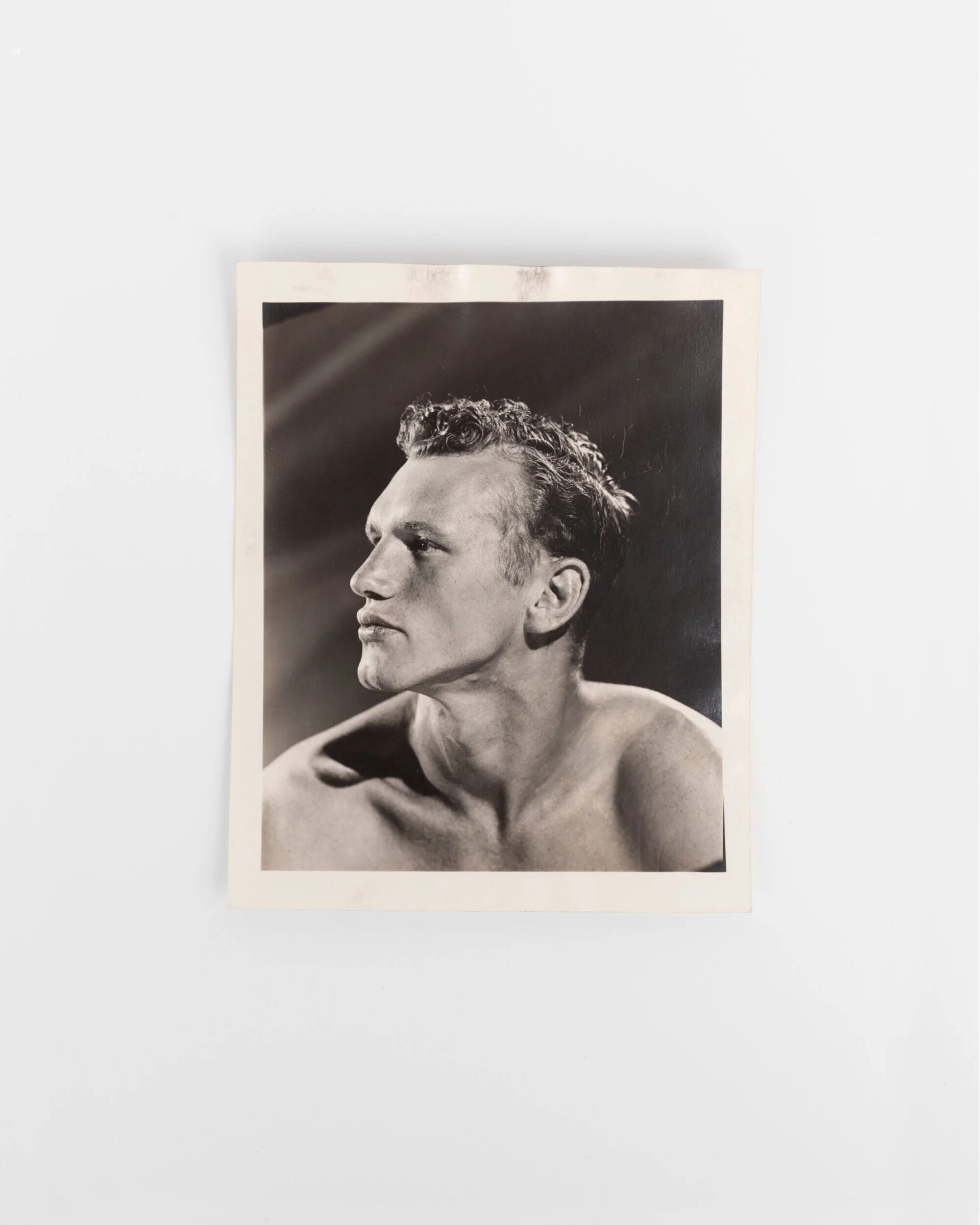

Ralph Eugene Meatyard: All the World’s a Stage

Ralph Eugene Meatyard, Untitled [Self-Portrait], ca. 1964-65.

All Images © The Estate of Ralph Eugene Meatyard, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

by Lev Feigin

The critic Roland Barthes once wrote that “photography touches art not through painting but through theater,” reminding us that before Daguerre presented his silver-coated plates to the French Academy of Sciences, he was known as a proprietor of a Diorama theater, a popular Parisian spectacle of lights and painterly backdrops. The dramatic stage is implicit in the camera’s frame. Its shutter curtain lifts to immobilize the human face into a mask, the gesture into a pantomime.

Barthes’ words are useful to keep in mind when looking at the work of Ralph Eugene Meatyard. Few twentieth century photographers have explored the elusive connections between the photographic image and theatre with such haunting poignancy.

Meatyard was born in Normal, Illinois and lived in Lexington, Kentucky where he plied his trade as a full-time optician. In 1950, he bought a camera to photograph his newborn son. A self-taught photographer, Meatyard would continue to call himself a “dedicated amateur”, even after his photographs were exhibited alongside those of Ansel Adams and Edward Weston.

By the time of his death, in 1972, Meatyard would produce a vast body of work, thousands of extraordinary images, from Zen-inspiring abstractions to his surreal take on the Southern Gothic.

Working six days a week, Meatyard took pictures on Sundays. While the rest of Kentucky attended church, the Meatyards – his wife, Madelyn, two boys, Michael and Christopher, and little Melissa – packed into the family car and drove all around the state in search of abandoned houses and creepy stretches of forest where they could perform their illusions. They brought with them a miscellany of props: dolls, masks, dead birds, even rubber chickens.

Meatyard staged the photographs like primitive theatrical rituals. The family scouted for a setting. The father composed the scene through the viewfinder and then positioned his subjects, telling them how to stand and where to look.

Ralph Eugene Meatyard, Lucybelle Crater and bakerly, brotherly friend, Lucybelle Crater, 1970-72.

The children stooped in tall grasses in empty front yards, leaned against broken doorways in clean, white T-shirts as they faced the lens looking forlorn, cowering, casting glances at derelict corners of domestic ruins – their hands juxtaposed against weathered planks of wood. They peered from the crosses of window sashes. They sat on empty porches, crouched and closed their eyes among shafts of sunlight. They became blurs. They morphed into silhouettes while black paint smears on the walls hung over them like the Grim Reaper.

In 1959, Meatyard bought Halloween masks at the local Woolworth’s. With flayed, peeling skin, wrinkles, idiotic grins, and macabre expressions, the masks were a marriage of Japanese Noh with Hollywood horror: disturbing psychic states frozen in blubbery latex.

In Untitled, his daughter, Melissa sits cross-legged on the rocks. Her small, childish hands prop up a woman’s mask as if holding her own adult persona. Hollow portals into the uncanny, the woman’s eye sockets are as black as Meatyard’s doorways: the shadows and the highlights meticulously placed in the darkroom to enhance the dramatic effect.

Locked away inside their father’s fictions, the children and their mother donned the masks among dejected ruins and sunless forests. In “Romance (N.) From Ambrose Bierce # 3,” the family sits on abandoned Little League bleachers in their disfigured masks. In the front, a blond woman (Melissa) with two teeth and a crooked hag’s nose spreads her legs; to the left, a short man (Christopher) with half of his face flayed off, keeps his hand on the thigh; in the center, a taller man (Michael) with a cleaved forehead and nose slouches with an air of resignation; at the top, a troll (Madelyn with a mask on her thighs) leers with an off-kilter grin. Numbers, one through five, run up the benches, quantifying the ineluctable.

The lens transmutes the children and their mother into allegories of isolation and mortality. The scene emanates an emotion that is not easy to name or locate in the masks themselves. The figures exist on the threshold to another preternatural order, which they have been called to guard. Their bodies betray the actors under the guises, but the dramatic hybrids of children/adults, whose recognizable selves have been conflated with the masks, distill an uncanny sense of disjunction.

Meatyard never subscribed to the notion that photography can strip the veil of appearance to reveal and objective truth. As a friend and mentor, Van Deken Coke, had once pointed out, Meatyard “was a picture maker, not a picture taker.” To the veil of appearance, he brings more veils. Behind his masks, there is always another mask – or nothing at all.

Ralph Eugene Meatyard, Untitled, 1957-58.

Ralph Eugene Meatyard, Romance (N.) from Ambrose Bierce # 3, 1962.

In Untitled (1957-58), a man sits in a boat listing in dry grass and removes a woman’s mask under which he is wearing mascara and rouge. The boatman is missing an arm; his shirt sleeve is folded over the stump. A broken mirror – Meatyard’s leitmotif recalling René Magritte – reflects a cloudy sky. The sitter is the photographer Cranston Richie, who had lost his arm to cancer. The image is like a Zen sermon told in a dream.

Meatyard began his final major series, the Family Album of Lucybelle Crater, just before his own diagnosis with terminal cancer in 1969 and continued the project until his last days. The sixty-four image cycle shows his wife, Madelyn, in a witch’s mask with a rotating cast of friends and family. The series was published posthumously in 1974.

Everyone in the portraits is named Lucybelle Crater. Madelyn wears a mask of a hag with two teeth and a crooked nose. Her companions wear the mask of an old man with deep wrinkles and narrow, squinting eyes. The name of Lucybelle Crater is inspired by Flannery O’Connor’s short story “The Life You Save May Be Your Own” about a mother and her deaf-mute daughter who are both named Lucynelle Crater. But the images are far removed from either the Southern Gothic of O’Connor or Meatyard’s earlier dark fairy tale realms. The Lucybelles stand among emblems of American suburbia – shiny station wagons, houses with white siding, chain-linked fences, driveways. The looped repetitions of masks and names impose an uneasy sameness on different bodies and backdrops. The normalcy of middle class America is contorted by the presence of masks. The ironic titles scribbled under each portrait, such as “Lucybelle Crater and her 40 year old husband Lucybelle Crater,” cast the images further into the realm of the absurd.

Meatyard’s friend and photographer, Roger May, called this series his “last sermon on the use of the mask.” The figures look tender and are often touching. If not for the masks, the portraits could have been snapshots from a real family album. Their matter-of-fact quality heightens the enigmatic effect. The masks are donned to say goodbye. Behind them is the spirit of Meatyard himself, a bookish, brilliant artist obsessed with literature, painting, philosophy, and Zen, whose truthful illusions explore the meaning of things beyond words.

Ralph Eugene Meatyard, Lucybelle Crater and bakerly, brotherly friend, Lucybelle Crater, 1970-72.

Ralph Eugene Meatyard, Untitled, 1970-72.

![Ralph Eugene Meatyard, Untitled [Self-Portrait], ca. 1964-65. All Images © The Estate of Ralph Eugene Meatyard, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco ](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5702ab9d746fb9634796c9f9/1611608558020-ANHQEH3IJ6UDDQQDS7XS/FINAL.jpg)