#WHM Erica Baum

We’ll be tapping our incredible archives in support of Women’s History Month and International Women’s Day and posting interviews from our Women issue throughout the month of March.

Erica Baum straight shooter

Portrait by Andrea Blanch

Interview by Andrea Blanch

One thing I find fascinating about your story is your lapse between undergrad and grad. Why did you decide to make that jump to grad school after so long?

It wasn’t really a jump because in high school I was always doing art. I grew up on the Upper West Side and most of my friends had gone to art high schools. The arts were completely normal, and the role of an artist didn’t seem so out of reach. When I went to college for anthropology, I was thinking I might go for a doctorate, but I was also thinking anthropology was something that my art would ultimately be about. I used to paint, but photography made the most sense in conjunction with anthropology.

After I finished college, I had a choice between a couple different routes. One was an unpaid internship with an NGO about Africa, and the other was a paid job in a non-profit arts administration that gave grants to artists — and, I took that one. From that job, I started working for the parks department doing public art. We would go to communities all over the city and work with them to develop murals on park properties. I always documented what we did, and my boss started saying to me, “You should consider photography.” In the summer, we would hire more people to work with us, and they were all artists with MFAs. I was the acting artistic director for about six months, but because I didn’t have the right credentials, there was never any thought of me staying there. It gave me the sense that an MFA was a practical thing.

In graduate school, my body of work evolved into a voice that reflected my interests, bringing together language, and my undergrad studies in anthropology, literature, and linguistics. All these threads in my work took a lot of time to germinate.

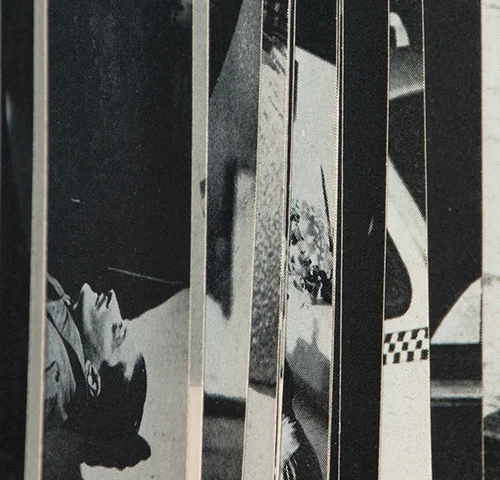

© Erica Baum

Can you speak a bit about the upcoming show at the Guggenheim? What is the idea behind it?

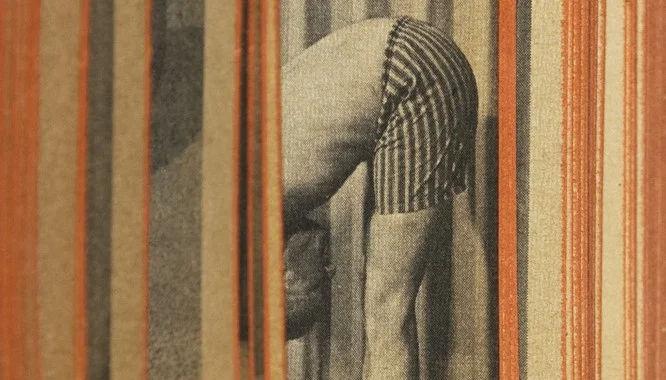

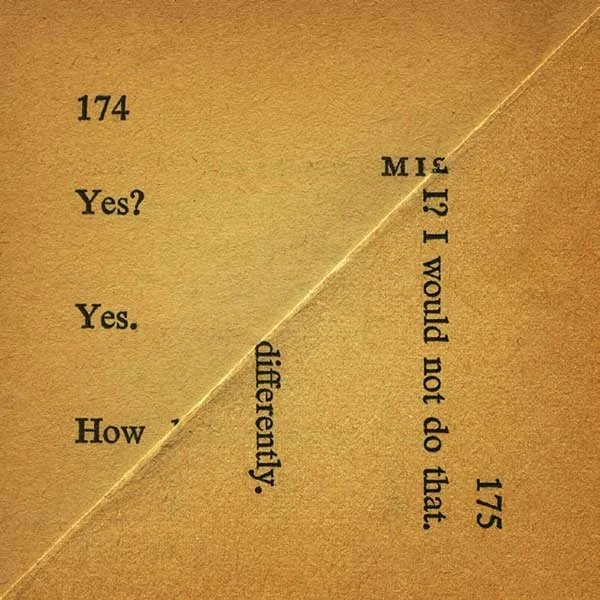

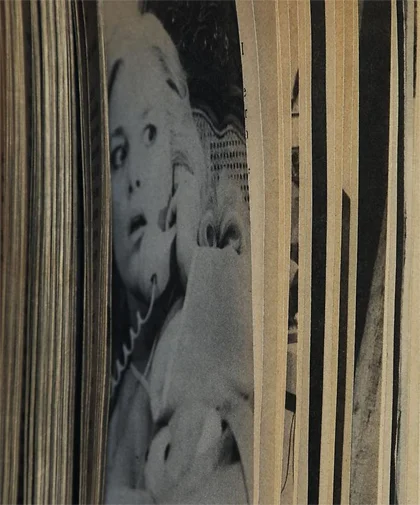

In my case, there were a few pieces that were acquired by the Guggenheim a number of years ago, and the curator [Jennifer Blessing] used those pieces as the principle for the way she made my selection. She chose seven Naked Eye pictures, and in addition to that there are some text-based works that I call Newspaper Clippings. I had done another book called Sightings with OneStar Press, which is a press in Paris. It’s all about UFOs, fact and fiction, and playing around with found text and witness’ descriptions. In a way, it ties in because when I titled the series “The Naked Eye,” I was thinking about those witness’ descriptions. The thing about the Naked Eye photographs is that they look like a collage, but they are really deadpan, straight photographs. Again, it’s that mixture: a very straight thing that suggests fiction. In the book, I combined a series of sequences, including the Newspaper Clippings, a series of shadows that are all black and white and I also included some Naked Eye’s in there. There is another element to the Guggenheim show based on an installation project I did at a large space in Switzerland. I made installations by enlarging some of the photographs I’d taken, and pasted them like posters directly on the wall. In the Guggenheim, there is going to be one installation like that. So, you’ll see Naked Eye, and you’ll see this installation, and you’ll see a set of Newspaper Clippings on their own as well.

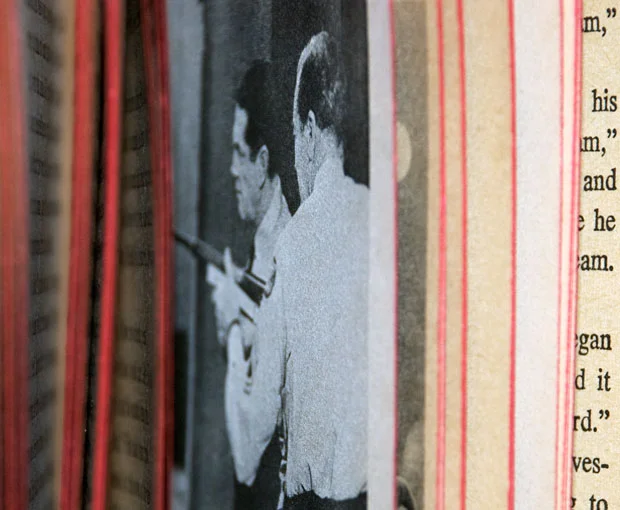

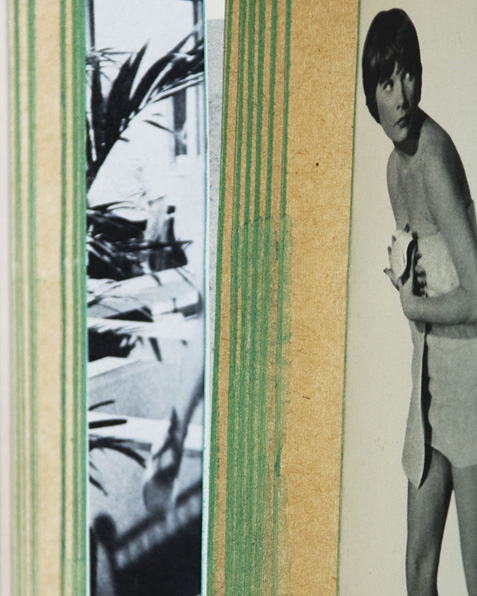

How did you make the Naked Eye pictures?

They’re just these old, mass-market paperback books. I open it up, and it is just the angle and the juxtaposition. It really is just a straight photograph; that is the thing that is so exciting to me. I love collages, and this is a found collage. It’s very minimal. I just hold the book open. Sometimes I use a pencil to keep it open, but I try to be very low-tech because that’s the spirit of the project.

© Erica Baum

Do you think it’s important for a young photographer starting today to have a degree?

I wouldn’t say it always is, but it seems more important now than it used to be. Richard Benson didn’t have any degrees and he’s totally important. But it feels like the world has changed a bit. A lot of people do go in for teaching, although at Yale, at least in my day, they weren’t looking for people who were thinking of it that way. They wanted people who focused on their work. What was great about that was you were suddenly immersed in a world where people take photography so seriously.

Would you recommend MFA programs? Someone said to me, “You could go over to a residence, and you don’t have to be $100,000 in debt.”

That’s a good point. It wasn’t as expensive when I went. It’s gotten much harder. The consideration there is greater now. For me, I felt like I hadn’t addressed something really important for myself. So going to graduate school was a way to be fully committed, to take that risk.

Do you think the art market has changed so that such an emphasis is placed on an MFA now?

The way people have their MFA thesis shows now, it’s like they’re having a solo show. I had a friend who graduated from Hunter College, and I went to her show in the early 2000s, and I was amazed. There was a book, you signed in, people made cards. Everybody was basically saying: “Here I am. Scoop me up.” In our day, we had our MFA thesis show in New Haven, and you didn’t expect anybody to see it except your family and friends. It was just the culmination of your work. That was it. Now, people think, “OK. I’ll get someone before anyone else can, and promote them.” That’s part of it, but also, if you want to teach, you need an MFA. The programs perpetuate themselves.

© Erica Baum

I think it’s good in one way, but it puts a lot of stress on young artists…

Yeah, instead of feeling like school is your time to explore, you feel the pressure to succeed immediately. I felt a lot of pressure anyway because I was older when I went back to school. The people who are ten years younger than me could go ahead and try something new every month. That might annoy the teachers, but it was good for them to just try stuff.

It seems like the way people are doing art now is much more experimental…

All the mediums are getting more blurred nowadays. At Yale, media is organized by department, but that’s not the way things are going. On the other hand, the ideas that coalesced for me in school are the ideas that I carry with me. Like the questions, “What’s ephemeral? What can photography do in particular?” These are still of interest to me. It was a big conversation when I was in school — the fact that nothing is really real and, to some degree, it’s all fiction. Those were the kind of conversations we were having. All those things inform the way I consider what I’m doing when I start a project.

© Erica Baum

What do you see as being the relationship between photography, linguistics, and anthropology?

The ways I choose subject matter and think of the world comes from the ideas that were important to me in anthropology: about institutions and structures, looking at things as artifacts, and what they reveal about the world around us. My series Card Catalogues is about the library system and the incidental information that comes about through it. It’s always about reflecting our world. I did a couple of shows that I called The Public Imagination, which is about the way in which something can reveal a voice. This is kind of the zeitgeist voice, or the world of the public imagination. Linguistics is about the musicality of language, thinking about language as an object, and being a little distant from the language so you’re thinking about the mechanics. The way words work, the musicality and poetry of it, and even the look of it, that’s where the linguistics takes place.

When did you start experimenting with abstraction and photographing found objects?

In graduate school, I had been photographing using a medium-format camera doing straight photography of student life. I taught some of the undergrads photography, and, in exchange, I was given permission to go behind the scenes. So, I was photographing aspects of student life, like at the library and parties, and on the lawn. I started becoming more aware of textures, little bits of things around the school. I started using a large format camera to photograph blackboards. That was a really exciting breakthrough — the sound bites of language and the visual feel, and the fact that it had a reference and a source that was recognizable. All those things came into play, and that was exciting for me.

What artists, photographers, or otherwise have influenced your work and why?

I would say people like Walker Evans, Lee Friedlander, and Helen Levitt. It’s really hard to say only a few. I could just go on and on. In other mediums, I love Sister Corita Kent. I only found her work fairly recently. I saw a show of hers at MASS MoCA five or six years ago, but I felt an affinity with it. I just love artists like Ed Ruscha — people who have worked with language. I love Rauschenberg. I love Sol LeWitt. Every time I answer a question like that, later I think, “Oh, I should have said…!’”

© Erica Baum

© Erica Baum

Can you give me some examples of artists’ work?

There’s one Helen Levitt that says, ‘Bill Joan’s mother is a whore.’ Spelled H-O-R-E. And another one that says, ‘Press button to secret passage.’ I love her other work too, not just the ones that happen to be chalk. I guess because I grew up in New York and my family is from New York, there’s that feeling of connection. With Walker Evans, I could give a million. But, there’s one where they’re holding up a damaged sign, and it’s near 14th Street. I love that precision of the description, and the humor and the language that comes in.

Your series Dog Ear has been published and read as poetry. Did you initially conceive this series as a form of poetry, or did it surprise you that it was received that way?

When I started doing it, I had been reading a lot of poetry. I had another series that I did prior to that of enlarged indexes. I was invited by a professor at Kelly Writers House at the University of Pennsylvania to talk to his students about poetry. That was a fun visit for me because it inspired me to pursue poetry more. I was reading a lot of Emily Dickinson, so when I started doing the Dog Ears, I was thinking about poetry a lot. I didn’t know how they would be received, but poetry was on my mind. I had some poet friends who were excited by it. I got invited by Ugly Duckling Presse to publish it because they’re poetry publishers, and they organize readings. So, the next thing you know, I was being invited to do readings. Initially, I was too shy to do it. So, I invited a friend of mine who’s a poet to read them. The Dog Ear pieces can be read in many different ways. She had a way she read them, and I suddenly realized, “Oh, I actually have a way I read them.” There was another time when I was invited to read and it was out of New York. Since then, I’ve read them a few times. I’m happy that they are considered poems.

© Erica Baum

You’ve talked about how series like Dog Ear, Naked Eye and Stills have a “high failure rate.” What elements have to come together in order for a photograph in one of these series to work?

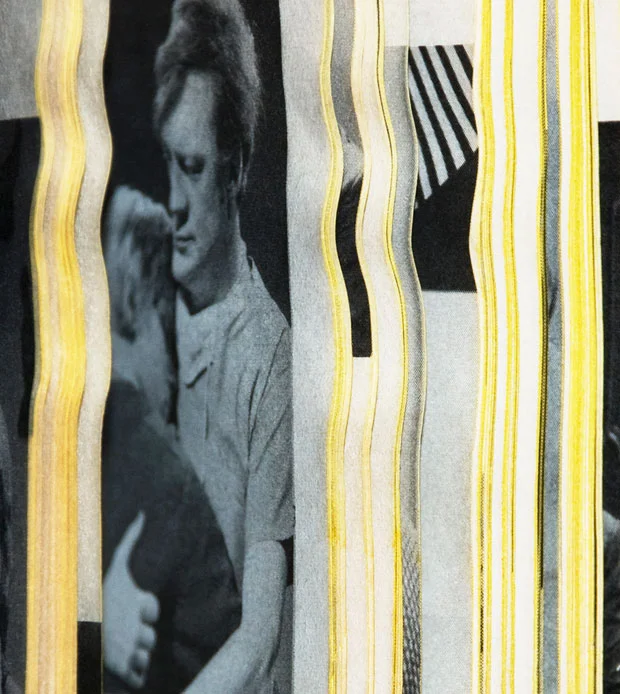

The longer I do any of these things, the higher the failure rate. At this point, I’m adding to a body of work and it may be redundant. So, I might reject it. Initially, and I would say generally, the words have to have a rhythm to them and it has to have a visual quality to it. It doesn’t come about that often, and I have to do a lot of them before I’m satisfied. I like to work that way. For the Dog Ears, it has to be read and it has to be visual. For The Naked Eye, I’m looking for certain expressions in people and often I want them to not be looking at the viewer — I mostly want them to be immersed in what they’re doing. I also try to expand it. Again, at this point if it seems too redundant, it’s not going to be that interesting.

What is it that you want to capture about our relationship to language?

I’m always trying to suggest that there is a voice that runs through things. For example, with the Naked Eye, the same book can generate different stories. There are these voices, and I’m looking for them. I like being surprised. One of the things I love about the Dog Ears is that I vaguely have an idea of what I’m looking for, but I’m always surprised by what I find. It’s somehow taking this process of searching and then letting that direct my voice. I still feel like I’m speaking through those things, but I’m not imposing what I’m going to say exactly.

How do you think being a woman has informed your art practice?

Going back to what I said about that first job with the artist registry, a lot of artists were women. It was important for me to see them and their practice. I went to high school with Jean-Michel Basquiat and Zoe Leonard. Jean became famous almost instantly after high school. It happened so quickly , so he wasn’t a role model because it just happened in a meteoric way. I would say Zoe Leonard is more the role model I could imagine because it took a little longer, and it had a different root. As far as women, I think that having a role model is always important. It’s always important for girls to have women they can look up to — acting practitioners.

© Erica Baum

Do you feel your Naked Eye series has something to do with scopophilia?

Yeah. I feel it’s a lot of things all at once. It’s as if it’s a curtain and you’re peering in. It’s voyeuristic.

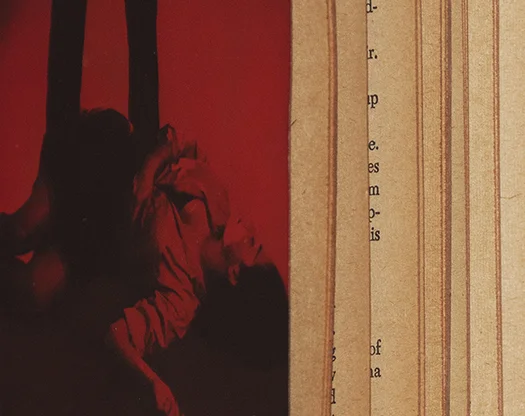

One review said that your work is like another state of being. What do you think about that?

I’m trying to give you something that, on the one hand, you have a feeling of where it comes from, but at the same time, it’s taking it somewhere else. I want it to have that vibrating sensation between the two.

What would you like the viewer to come away with?

I want them to appreciate the particularities of the source, that there’s an intention to the textures, the colors, the material, and the artifacts. I also want them to see the potential for poetry in it, visually and verbally.

What are you working on now? What comes after the Guggenheim?

I have a show that is opening in Paris in September at Galerie Crèvecoeur. I’m putting out a book with that gallery and the Gallery in New York of Naked Eye works that will be out soon, hopefully in time for the Guggenheim show. They want to do a second printing of the Dog Ears. There is a show at the Met I’m in that opens September 21st, called Reconstructions: Recent Acquisitions in Photography and Video.

© Erica Baum

© Erica Baum