Andrea Blanch: David Levinthal. Where and when did you go to graduate school? David Levinthal: I went to graduate school at Yale in 1971.

AB: Who was there then, because it's changed considerably?

DL: I went primarily because Walker Evans was teaching there.

AB: Whoa.

DL: I know. Sometimes when I tell students that, they look at me like, "And you're still alive?" Walker was there, Paul Caponigro, and there was a wonderful group of artists who came as visiting faculty - Ed McGowan, Linda Connor, Frederick Sommer came. It's funny when you're young. I was probably twenty-two. Having the opportunity to study with someone like Walker is something you fully appreciate later on in life. Obviously you're aware of what a significant presence he is in the world of photography, but I think you're really too young to appreciate it until later on. I remember being asked what kind of teacher Walker was when I was in graduate school, and I think it was more about him as a person and being able to spend time with him. One of my classmates was Jerry Thompson. After graduation, Jerry and I got an apartment together in New Haven and Walker would often stay overnight there when he wasn't up to driving back to Old Lyme. I got to spend a lot of time around him which was a really fascinating experience. But again, I think you become more cognizant of it later on in your career as to what that meant.

AB: What do you think you learned from him?

DL: I don't know that there was anything really specific. I tell students things through anecdotes and stories, and that's something I think I really learned from Walker. Somebody will ask me a question and twenty minutes later I'll have gone through three or four ancillary subjects and then say, "Did I answer your question?" I think it's the experience. I never found myself asking Walker specific questions about what it was like doing 'Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.' But I think you got a sense that he knew all the people in photography who really laid the groundwork for where we are today, and listening.

AB: What do you think he would say, if he were alive today, about conceptual photography and how it's been accepted?

DL: You know it's interesting. Walker went to Paris as a young man to be a writer. He loved literature, particularly French literature. He was an absolute Francophile. In fact, a patron of his gave him a ticket so he could be on the last voyage of the SS France. I think of Walker as an intellectual, and photography was a vehicle, but it wasn't, for him, an end in itself. I think he would find some way to be doing something interesting. I started photographing the toys when I was in my second year in graduate school.

I remember back in those days when I was applying for teaching jobs, letters of recommendation were still confidential. This one university that I had applied for a job I didn't get, sent me back my portfolio and inside the portfolio somebody had inadvertently stuck the four letters of recommendation, including Walker's letter. Walker's letter was short but it was so touching to me because what he said was that he felt I was a very unusual and special talent and that I would be a great asset to any photography program. He never said that to me personally but I was very touched that even though I was off doing this crazy wacky thing, that he saw something in me and could project forward that it would be something of interest and significance.

AB: It seems that you have an awareness of political and social issues. Where does that stem from? How does that tie in to your work?

DL: Yes. I went to college in 1966 at Stanford with the intention to be a constitutional lawyer. It was the 60s and I came from a liberal household. The 60s were very a transformative time. Law seemed a way to pursue social justice and changes. So, I was going to be a poli-sci major and go off to law school and obviously, things changed. It was also Bay Area '60s. The Free University which was essentially non-credit classes, totally unstructured. Anyone could teach a class on anything. One of the classes, and I tell students this story, there was a class called LSD and Tantric Yoga.

AB: I knew I went to the wrong school.

DL: I took this photo class because it was taught by someone who was the sort of essence of coolness and I thought, "Well, Dwight's cool. I want to be cool through all this, and all the beautiful women around him. This sounds like a good idea." And so I signed up.

AB: Are you shy?

DL: Yeah. Which is funny because when I came to New York in 83, I forced myself to be social. You're always told to go to openings, meet people, which is not easy, but I looked at it as a job. I needed to do these things.

AB: Where are you with your work now? Are you still doing social landscapes or you're doing the toys?

DL: No. Once I started working on the toys in graduate school, I continued. Actually, Garry [Trudeau] and I, after we graduated in the summer of ‘73, his publisher suggested that he and I do a book together. He had created a biography of a faux German Luftwaffe (the pilot), and done it all with graphic symbols. His publisher saw Garry's work, and my work at that time was very simple. I had been photographing on the floor with minimal backgrounds. They said, "Well, you know, you two guys should do a book together." We looked at each other and thought, "Well, that sounds like fun." We got an advance of $1,500. I remember when Garry gave me my check for $750. He looked at me and he said, "Now, just remember if you cash this check, we actually have to produce this book." Now, our contract said we had a year to do it. It took us three and a half years, for lots of reasons. One, Doonesbury was becoming such a significant force in the social and political landscape. I think Garry was the first cartoonist to get a Pulitzer.

I was taking pictures with unpainted tiny little figures to the point where the images in the book were all of these larger models that I had made and painted, much more articulated.

I remember Garry's explanation to Jim Andrews and John McMeel, he said, "Well, the reason it took us longer to do the book than it actually took to fight the war was that we have to clean up afterwards." But my work evolved tremendously and spending that amount of time focused on it really brought me to the point where working with dioramas and toys became what I wanted to do. When the book came out in ‘77, I remember going to the B. Dalton's Bookstore because I wanted to get a copy for my parents that was wrapped up in their paper. They had it in the history section because there was no photography genre that it really fit into. I find it so interesting that Garry and I just did a reissue of the book, a 35th anniversary edition. Garry's suggestion was that we do it larger, a bigger book and I said, "Is that because we're both over sixty and this is the big print edition?" His feeling was, and he was absolutely right, was that it gave a great presence to the photographs. At that scale, they seemed even more powerful.

AB: They are.

DL: It's very gratifying to see work that you've done become even more relevant and more significant. I remember years ago, Elizabeth Sussman at the Whitney took Garry and I to lunch and there were some 'Hitler Moves East' photographs and a couple of his layouts from the book. As we're walking through the Whitney, Garry looks at me and he goes, "Did you ever think when we were sitting in New Haven, eating hostess cupcakes and drinking Coke that this work was going to end up in a museum in New York City?" I think part of the reason that 'Hitler Moves East' is the way it is, is that we were so oblivious to any boundaries or constraints. Looking back on it, we were breaking all kinds of rules and things but that's not what our thought process was. I would think, "Well, how can I make a wheat field? How can I make snow?" It turned out the wheat field was grass seed and the snow was Gold Medal flour which I continuously recommend to students who want to create snow. It's one of my favorite photographs. One of the signature pieces, the explosion where there are soldiers flying to the mid-air, Garry stuck a pin in one of the soldiers and so he propped him into my little mound of grass which he used to refer to as my miniature golf course. It was about three by three feet on this big table I had. I had sprinkled a little explosion powder and Garry lit it with a cotton ball and it kind of went poof. He said, "Here, give me this." And he starts shaking it like an eight-year-old putting salt on French fries. He lights it. There's this sound like a shotgun going off. The cotton ball flies across the room hits the window and bounces back. The negative is almost opaque but it was this great photograph that literally looks like the soldiers flying to the air. Garry said, "You know if I knew you were having so much fun doing this, I would come over more." There was just a completely unstructured exploration of how do we do this and without any regard to what would be considered traditional photographic work.

AB: Is your lighting setup complicated?

DL: No. Most of the time it's embarrassingly simple. 'Hitler Moves East' was done in my apartment in New Haven using one of those old-fashioned, big metal reflectors that you put the light in. It was a metal dish and I bounced the light off the ceiling. That was it except for the light that came from when I would light a building on fire. That was additional lighting. I would say now it's probably more sophisticated because they make lighting specifically for tabletop work.

AB: Were the 'Wild West' and 'Desire' series commercially successful at first?

DL: I'm glad my wife isn't here... I had an old girlfriend who was a curator and she said, "Your work is always going to be discovered five or six years after you do it," like the American Beauties which are now pretty much all gone. So, they weren't too commercially successful at that time. They sold a little bit. I would say with the exception of the cowboys and Barbie, there's always been this sort of lag between when the work is done and when it starts to sell, which is hard at that time. But in retrospect, it's kind of great because I still have the work, and the prices have gone up considerably, and essentially all the 20x24s are vintage prints. I mean people are still doing some 20x24 work, but it's not really the same.

AB: Have any fashion people ever approached you to do something for them?

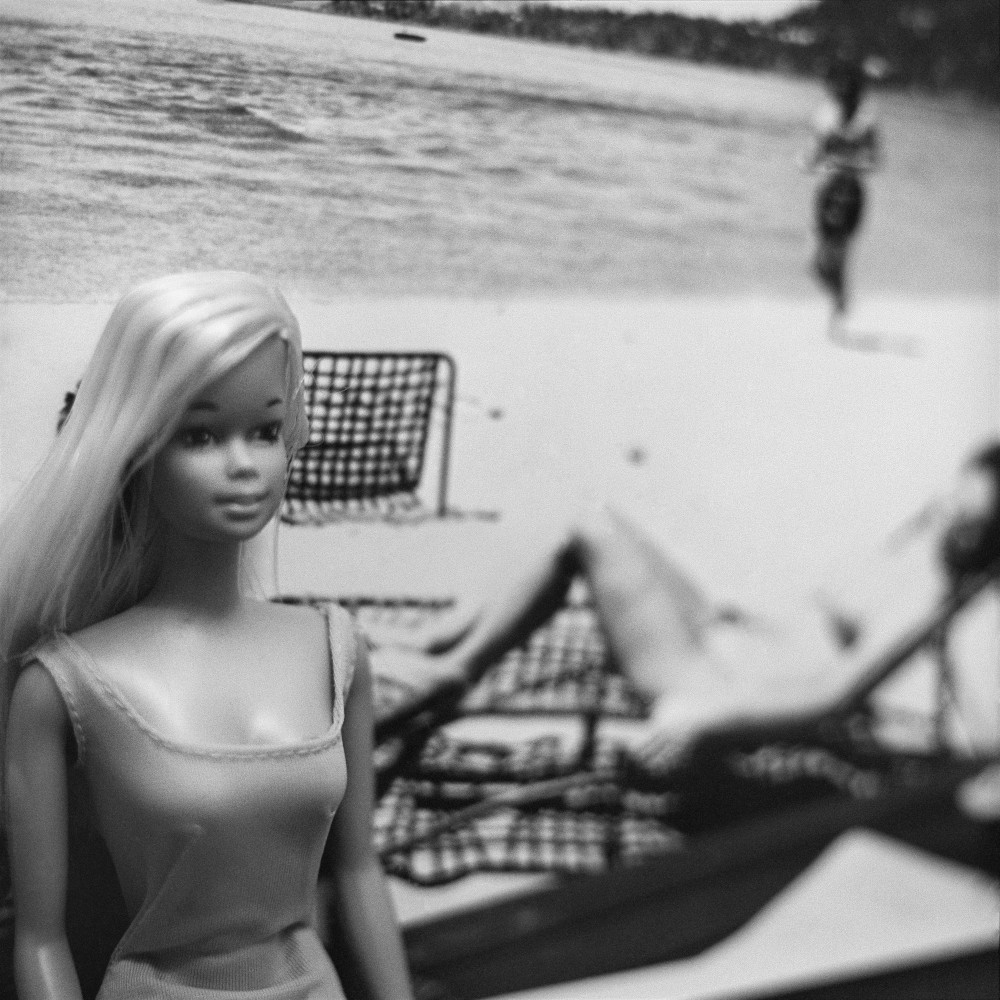

DL: I think the closest I came was the Barbie project. I was asked by a publisher to do this book for Barbie's 40th birthday, which was 1999, and I initially said no because I had photographed a Barbie doll in grad school with a G.I. Joe and later I showed the work, I guess maybe four or five year ago, with John McWhinnie. We called it Bad Barbie.

Years later, it's now high art and very expensive. But the Barbie book, they asked me again and I had actually just for some reason, I think had seen Funny Face on AMC and I thought to myself, "Well, if I approach this like I am a fashion photographer, this is going to be the only opportunity I ever have to be a fashion photographer."

I took a late 50s, early 60s approach to it that you saw in the movies of those days, like what Audrey Hepburn or Doris Day were. I picked colors with that time period in mind, a bright pastel type color. It was a fun project and I think that's one of the reasons why we ended up focusing so much on the earlier Barbies that really had a fashion sensibility about them.

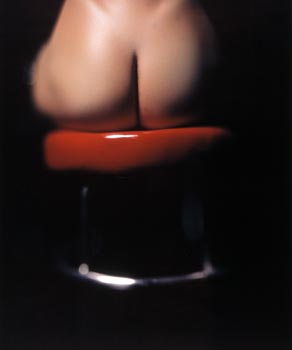

But no, I've never been asked to do fashion work, although I've always felt that there's a great deal of similarity. I said that when I was doing the Triple X work that it was like I was photographing Playboy bunnies. They had equal amounts of artificiality in them. Mine had the advantages of they weren't going out at 3:00 in the morning and doing drugs, and they were all set to go at 10:00 in the morning.

AB: What is something you'd like to talk about and that you've never been asked?

DL: I remember when I was in graduate school I was sharing a house with two third year law students and I remember one of them asked me, "What happens if you run out of ideas?" And I remember saying, "Well, it never even crossed my mind." I feel in some ways I'm more concerned about staying around long enough to work through the ideas I already have because there's just so much. One of the things that I find really interesting and kind of liberating about doing these historical iconic images is in the past I might do an entire series say of the Civil War. Now, I can pick moments like Lee's Surrender or a charge of Gettysburg and so it's very, very liberating, and it allows me to sort of delve into something without feeling that I have to complete it.

AB: When you create your work, do you think about the person who's going to be looking at it and what kind of response it's going to evoke or provoke in them?

DL: I think at this point it doesn't cross my mind. When I was younger I would from time to time think about it, but I've always looked at my work as problem solving. I have an idea of what I want. I may end up with something completely different, but I'll really focus on that as a starting point and then I let the work take its own direction. I always tell students, "You start out with an idea and you may end up some place completely different, and allow yourselves to do that."

AB: In your own words, how would you describe yourself?

DL: Introspective, lost in my own world...

AB: When did you start thinking of yourself as an artist?

DL: Probably when I went to graduate school. I would guess because as an undergraduate I was a film major briefly, a classics major, I took a nuclear physics class and my father was a physicist. He told me, "You don't have to be a physicist because I'm a physicist." He talked to a couple of his friends in the art department including Professor Conn and Matt said to him, "Yeah, you know David really has talent," which was very nice to hear. But my father said something else. I remember we were sitting in the car in the car port, he said, "Talent is necessary but not sufficient criteria for success." I found that to be so true. There are so many other factors that come into play, some of which you have no control over. I was very, very fortunate that Garry and I were offered this opportunity to do the book because having a book of your work published when you're twenty-eight years old is a big deal. It meant that that work was going to always be out there in some form. I'm grateful that I had those opportunities, and things have not always gone smoothly, they never do.

AB: What's your fantasy?

DL: That I can live long enough to do all the work that I would like to do.

David Levinthal began to focus mainly on toys as a subject matter in 1972 while in graduate school for photography at Yale. His work touches upon themes of American culture and moments in history; everything from WWII battles, barbie dolls, and baseball legends. Using small figurines and simple lighting techniques Levinthal brings to life inanimate objects which otherwise contain little substance and drama. He has produced politically charged and controversial work. His books include: Hitler Moves East, Baseball, The Wild West and Modern Romance. He earned a BA in Studio Art from Stanford University in 1970, an MFA in Photography from Yale University in 1973 and a Scientiæ Magister in Management Science from the MIT Sloan School of Management in 1981. In 1995 he received a John Simon Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship and also a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship in 1990-1991. He lives and works in New York City.