The Stroll, Zackary Drucker and Kristen Lovell

Courtesy of HBO Documentary Films

Written by: Michael Galati

Edited by: Kee’nan Haggen

“The Stroll” is a term used to describe 14th street in the Meatpacking District of Manhattan in the 80s and 90s that transgender women sex workers and their clients occupied. The term is also the title of a documentary film released this summer, co-directed by Zackary Drucker and Kristen Lovell, a former sex worker on The Stroll herself. Together, they’ve created an archival project of community history, including interviews with 11 trans sex workers, such as ballroom legend Egyptt LaBeija and activist Ceyenne Doroshow, creating a keepsake of what the community has endured and a capsule of resilience for whatever may come next.

“I have arrived now,” says Lady P, a tall, curvy woman, as she walks onto The Stroll just past midnight. She’s glitz and glammed up, clad in a sequin gown and fur coat, face made up and ready for the long night shift. Headlights interrupt the continuum of the dark. The click-clack of her heels punctuates the silence. A man pulls up in a car. She asks him, “How are you doing, baby?” He offers a slight murmur. She carefully opens the door to his car, gets in, and drives toward the West Side Highway.

“The Stroll” is a term used to describe 14th street in the Meatpacking District of Manhattan in the 80s and 90s that transgender women sex workers and their clients occupied. The term is also the title of a documentary film released this summer, co-directed by Zackary Drucker and Kristen Lovell, a former sex worker on The Stroll herself. Together, they’ve created an archival project of community history, including interviews with 11 trans sex workers, such as ballroom legend Egyptt LaBeija and activist Ceyenne Doroshow, creating a keepsake of what the community has endured and a capsule of resilience for whatever may come next.

Courtesy of HBO Documentary Films

Drucker and Lovell are careful not to separate the experience of trans sex workers being on The Stroll from the material boundaries between trans sex workers and mainstream society. As such, the place in which sex work took place is inextricable from the work itself. Interviews with art gallery owners, meat packers, and, of course, sex workers who worked and lived in what was once the dilapidated area around the West Side Highway show that the Meatpacking District at the time was an otherwise abandoned neighborhood. Through these same interviews and archival footage, however, Drucker and Lovell elicit the immense joy and ironclad sense of community that trans and other queer people created there. Where no one else desired to go, queer people found family.

What the film does particularly well is detail exactly how this neighborhood went from a film noir-esque hub of fetish and S&M bars, gay cruising, and sex work to an ultra-luxury nest of wealthy NIMBYers. Giuliani’s “stop and frisk” and “broken windows” policies became the preamble for Bloomberg’s post-9/11 economic and aesthetic restoration of the city. In the neighborhoods Giuliani left vacant by putting people of color, queer people, and young people in jail, Bloomberg pumped hundreds of millions of dollars worth of commercial and residential real estate, turning grit and underground culture into a contemporary Madison Avenue. With this piece of history, Drucker and Lovell show, in a very Sarah Schulman-type way, how geopolitically induced fear and economic insecurity displace and often destroy the culture created by social, political, and economic outcasts. While everyone is affected by such fear and insecurity, the most vulnerable are categorically precluded from protection.

Courtesy of HBO Documentary Films

In doing so, Drucker and Lovell embed into the film the disorientation of place and time, the feeling of losing your home, that the sex workers who revisit The Stroll years later experience. Where Lady P’s “I have arrived now” was once an unwavering claim to her gender and sexuality, the post-gentrification “arrival” becomes a question of “Where am I?” Indeed, at the end of the film, Lovell is walking with Izzy, one of the film’s interviewees, through the now unrecognizable Meatpacking District, adorned with Sephora and Google billboards, among the same cobblestone streets where they picked up tricks when Izzy breaks down into tears saying, “I can’t do this. I hate this place.” Where this scene may have been cut from other documentaries, its inclusion here brings gentrification and its effects to life.

Courtesy of HBO Documentary Films

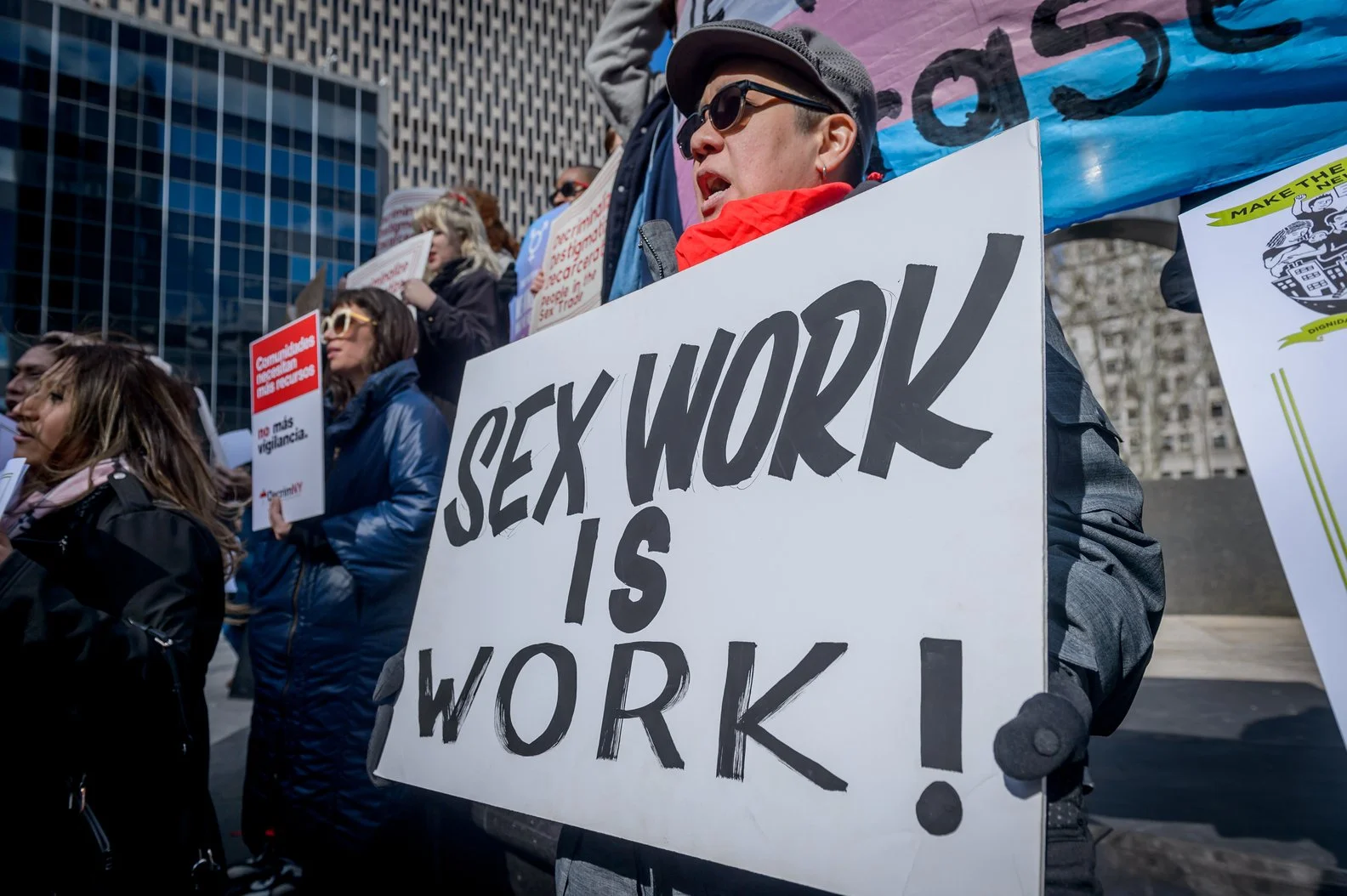

Despite these challenges, the fact that the film shows how they’ve been overcome inspires hope and makes it a masterpiece of queer history. It celebrates each sex worker’s iteration of “I have arrived now” but doesn’t cease the celebration there. Rather, the arrival process, the continual journey of coming to, does not end with each increment of progress. One of the last scenes in the film shows Ceyenne at the 2020 Brooklyn Liberation for Black Trans Lives March. She opens a speech in which she reveals that her grassroots organization, GLITS (Gays & Lesbians Living In A Transgender Society), raised nearly $1 million for the first-ever housing complex for queer people experiencing homelessness, with a triumphant: “We’re whores!” It’s the perfect summation of the experience of trans sex workers, women whose gender and sexuality have been the basis of their denigration, transforming it into the source of their power.

The Stroll is a piece of history that looks at an experience from every angle: historical, economic, political, gendered, sexed, and artistic, and it masterfully considers all these angles without giving undue deference to one over the other. It’s what a great documentary is: a time capsule of the past, a mirror of the present, and a telescope toward the future, but it’s not naive in looking forward. It knows there will be a pain in the progress. Lady P’s “I have arrived now,'' then turns away from the finality of arrival and becomes continual, unending coming to a better future while still carrying the painful history of progress with it.