Parallel Lines: Liza Ambrossio

Interview by: Federica Belli

Federica: What strikes me about your work is how it openly and boldly embraces the the instinctual behaviours, the madness and the boldness that our life requires to be lived to the fullest–especially as artists. In which ways has such extremely honest approach been therapeutic for you personally as well?

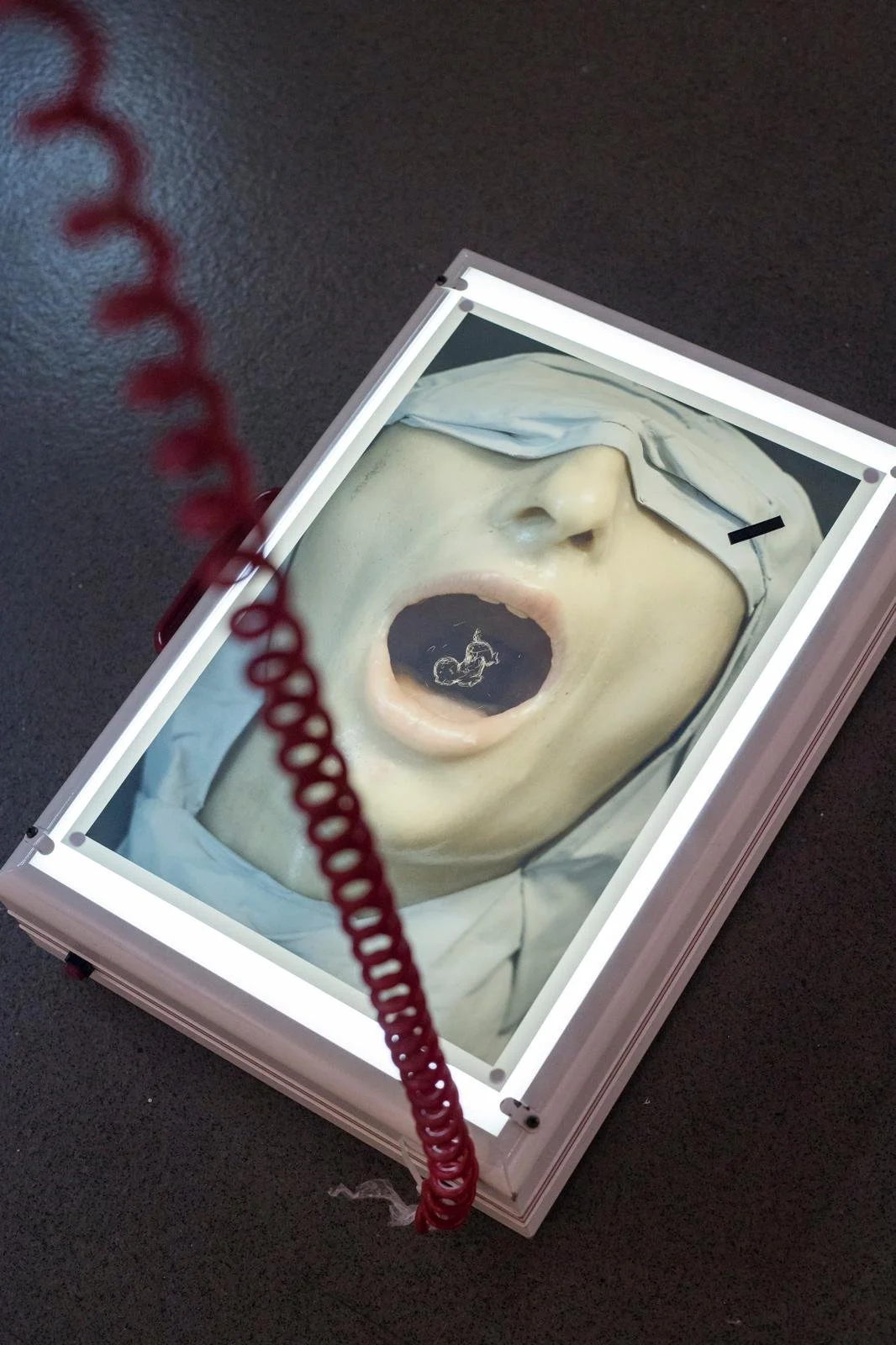

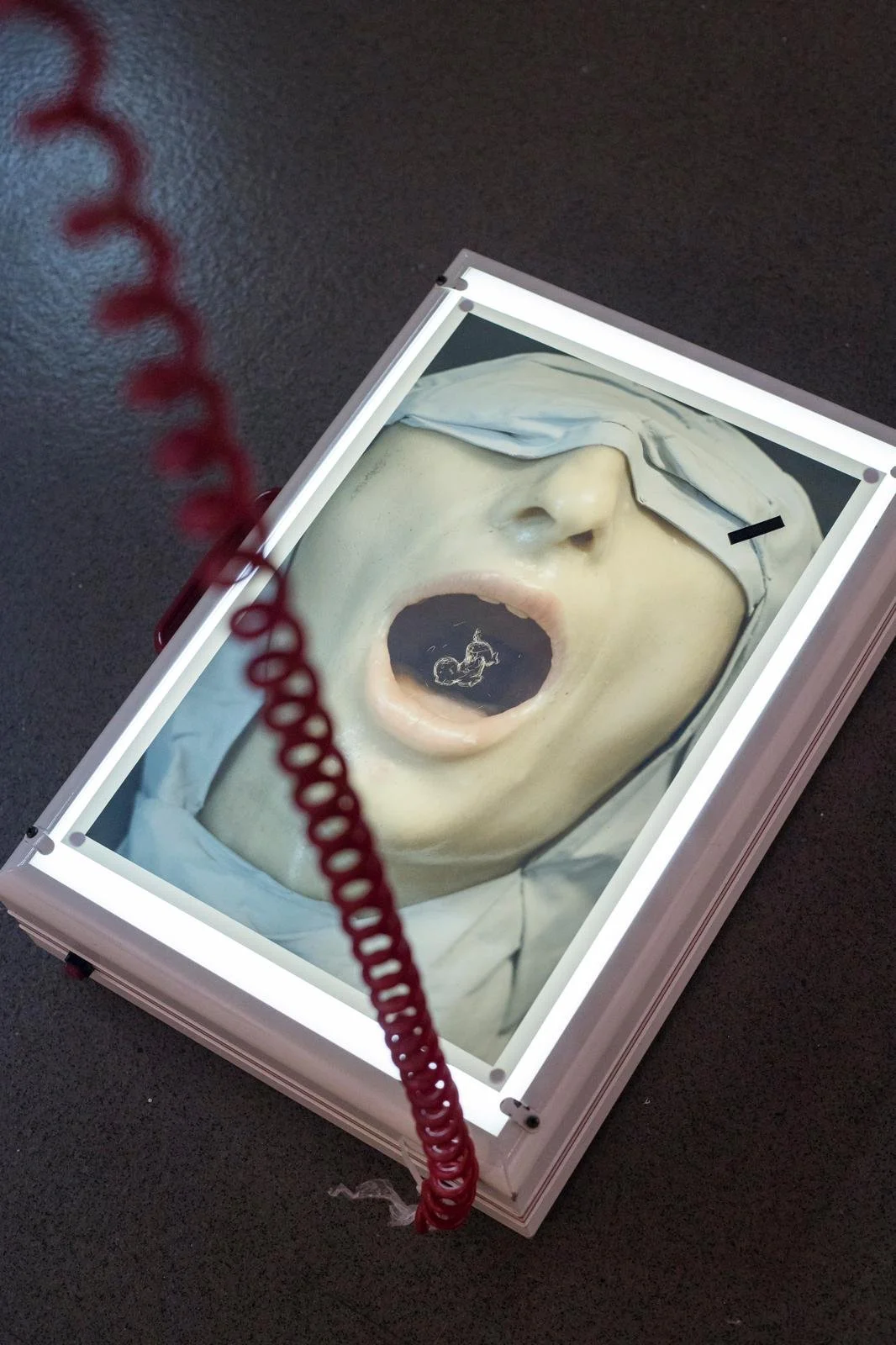

Liza: My works – specifically the ones in the series “The rage of devotion”, “Blood Orange”, “Too strong for fantasy”, “The witch stage”, “Traciones no aguanto para buenos los santos”, “Todos los niños huelen a lapiz”, encompassed for the first time in “Toda devoción causa ira”, presented in the “Sala Amos Salvador” in Spain and commissioned by the extraordinary friend and intellectual Javier Martin-Jimenez, accompanied by my third book and the first of art criticism where writes Ariana Rinaldo and Cuahutemoc Medina, published by the Spanish publishing house Pepitas de Calabaza – are a symbolic representation in the format of capsules, chapters or faces of different metaphysical, freely associated, real, mental, spiritual, political, alchemical and structural unfoldings. They are letters of love, hate, revenge, cruelty, madness, social responsibility, premonition, shamanism, theosophy, dreams, oracles, spiritualism, demonology, alchemy, astrology, life and death where evil is confused with madness and madness with evil.

Be it in the book, exhibition, performance, film or text formats, every time I conjure an idea that torments my personal history, choosing to present a private wound as fresh and raw meat to the public. I create a game of moral, mental and emotional dichotomies with deeply political, feminist and anarchist foundations, but above all I make evident a deep respect for the artistic universe – the last space of freedom and trust for those who no longer believe in God or in institutions. I always expected an “I admire you, I love you, I respect you…” from the state and my family but it never arrived, and that's fine... as nothing continues to happen in the inner hell of my mind or in the soul of the Mexican culture where I grew up.

I would say that the most fundamentally therapeutic idea that I have been able to describe in my creative and symbolic life is that my work as an artist is not only to enjoy the construction of interesting artworks, nor to enjoy the frivolous worlds among the palatial vernissages, the free dinners, the sponsored trips, the extravagant clothing and the slightest illusion of some male or female erotic attention. My job as a creative is rather to protect my work and make it greater than what I will become as a human being, giving it a drop of immortality while being absolutely aware that everyone will have to die. After all, what we artists are left with is the awareness of having seen, done, loved and rebelled something that only saints, serial killers and authentic artists can see, feel and make others feel.

Federica: In addition to that, your practice often goes beyond the language of photography, merging it with sculptural pieces and painted interventions. I imagine it to be an attempt to overcome the limits of the photographic medium, of which we are often not speaking. How do the different techniques complete each other in your work?

Liza: I am Mexican, coming from a culture in which the transition between life and death is unpredictable. In my work the need to unfold and be clearly understood as an artist with multidisciplinary work is fundamental for me. A basic mistake art historians do is wanting to pigeonhole artists to one practice, when in reality we are creating many at the same time. My defect and virtue is having won many awards at the beginning of my career in the photographic field – almost without intending to – but I guess the motivation to be photographic and not pictorial or anything else could be led back to having a life that was extremely nomadic and volatile, making it impossible to have workshops, spaces, warehouses, or assistants like I have now to make large-scale pieces. I am thirty years old, but I would say that with age and experiences my priorities have settled, and so necessarily have done my vices and voids. I am an artist and not a photographer, I have always been one, I restricted myself to photography simply because before I could not carry a thousand meters of work of art from country to country, while now I can handle it and more.

However, a specific piece that I have ended up loving – “Mistica Balistica” – is a virgin from the year 1550, one of the first to arrive after the conquest of Mexico by Spain, that had arrived to me after several generations in a family owning large estates and servants who said the piece was possessed. The funny thing about this is that the the one who commented on seeing her move, run, ruffle her hair and look at him was the great-great grandfather: in his senile stage the servants played tricks on him for having been violent with them in his youth, driving him to the point of madness. After his death, I decided to make a negotiation to have the piece in my studio in Mexico and I realized how beautiful she was: her hair was human, like her eyelashes and nails; her clothes were a mix between Spanish and very indigenous; she had something shamanic about her, she moved in all directions like a theatre doll. There I realised that the Virgin is the greatest feminist witch in the history of the world. She is a floating being, she is magical, wise, sensual and even with capabilities beyond what is understandable. The piece is an allusion to powerful femininity, to a scared woman, to the terror of the other, to violence and magic as a palliative to a poisoned world.

Federica: The exploration of human darkness and witchery is central to your work. And I personally see many of your photographs as self portraits even when they are not. Would you define your work as mostly autobiographical or explorative of the humans around you?

Liza: Edvard Múnich said “Do Spirits exist? We see what we see because our eyes are constituted as they are. What are we [but] an amalgamation of energy in motion, a candle that burns with a wick, inner heat, outer flames, and yet another invisible ring of flames? Had we had different, stronger eyes, we would, like the X-ray, only see our wicks, the skeletal system. Had we had different eyes, we would be able to see our exterior casing of flames, and we would have other forms. In other words, why should other with, lighter, insubstantial molecules not exist among us? The Souls of our dear ones, for Example? Spirits.” My work has a non-religious spiritual endowment, so what is inside is outside and what is outside is inside, something that I have only been able to assume from cultures such as China, Japan or some isolated regions of indigenous populations. You are right, my models and objects are representatives of my mental state, real or imaginary, that happens to artists obsessed with our way of seeing the world. And of course it is an autobiographical work because the personal is political and everything that interests me in art takes this unique tint. While the people I love or have loved are the human material with which I print all my work, I I'm not talking about specific people, not even about myself. I tell stories and those stories are gifts for the viewer and psycho-magical rooms for the viewer to find themselves in.