Book Review: The African Lookbook

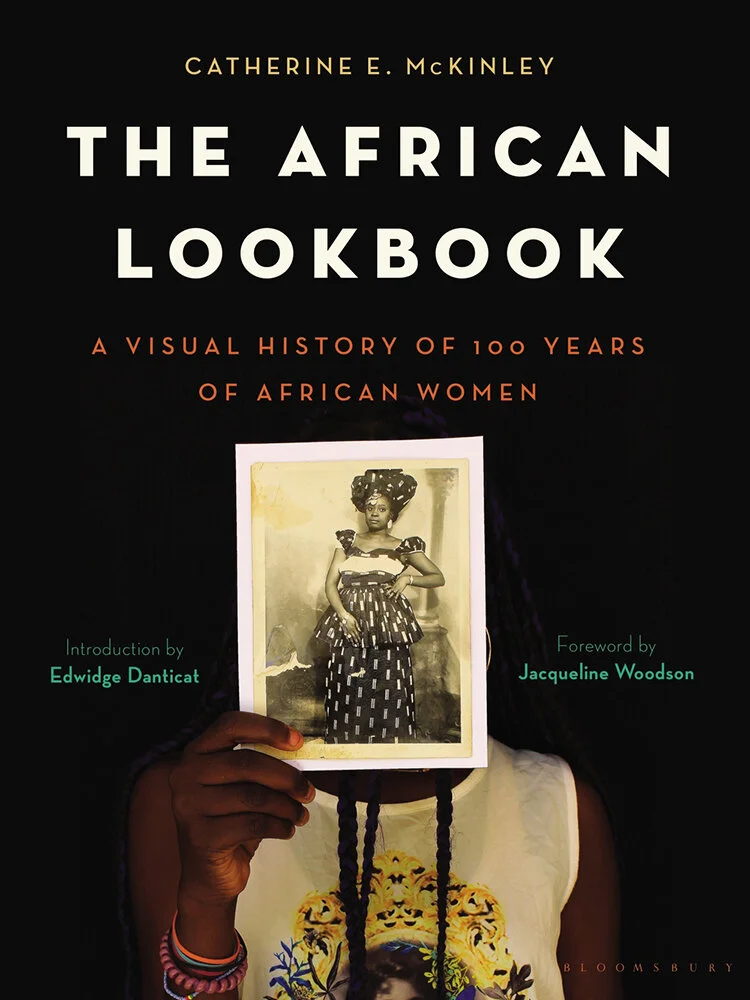

Cover, The African Lookbook © Bloomsbury

Text by Trevor Bishai

When we think of the mechanical innovations that have shaped the modern age, we are likely to think of electricity, the combustion engine, agricultural innovations, and advancement in heavy industry. But for Africa, and African woman in particular, Catherine E. McKinley shows us how two everyday objects—the sewing machine and the camera—became instrumental in shaping modern narratives. Her most recent book, The African Lookbook, illustrates a visual history of African women with an emphasis on photography and fashion.

Accordian, 1930, Unknown, Kapushi, Congo. Courtesy Bloomsbury

The book is a collection of over 150 photographs mostly originating from West African nations, among them Mali, Niger, Senegal, Sierra Leone, and Ghana. McKinley began consciously collecting these photographs in the 1990s and has since amassed a large archive of both vintage and contemporary images, whose formats include portraits, identity cards, stereographs, cartes de visite, and postcards. The range of her collection is wide—the authors of each image range from the anonymous or even unknown to some of the masters of African photography, such as Malick Sidibé and Seydou Keïta of Mali and James Barnor of Ghana. While McKinley’s images are diverse, those presented in The African Lookbook focus on the intersection of trade and fashion systems, and consequently, the photographers who established studios on similar routes. Arranged as a photobook, each image is accompanied by a short text, often including historical narrative on the photographers and subjects or more poetic, elegiac descriptions of the images.

Untitled #460, 1956–57. © Seydou Keïta/SKPE. Courtesy CAAC—The Pigozzi Collection

Focusing her first chapter on master African photographers, McKinley highlights the importance of fashion for African photography. Images taken by Sidibé and Keïta exhibit the lavish and opulent garb many African women wore in the 1950s, a few years before independence from Europe. Cloth, as she points out, has a quite significant history on the African continent, and has been used as a currency for generations, even up until the present. Fabrics with “traditional value” still today signify one’s wealth and social prestige. Cloth also became an important tool for women’s financial independence, a way for them to hold economic power in traditionally patriarchal systems. It is with this in mind that McKinley asserts the importance of the sewing machine—it allowed weaving and textile-production, practices traditionally done by women, to proliferate to a large degree.

The Young Ye-Ye Girls with Sunglasses, 1965. © Abdourahmane Sakaly · Mali

When photography came to the African continent, not long after the first daguerreotypes were being produced in Europe, it was exclusively in the hands of the colonizers, and as such became a useful tool for the colonial project. Photography was used to document and classify different African “races” and thus became an instrument of state-sponsored pseudoscience and colonial subjugation. However, cameras slowly but surely made their way into the hands of African entrepreneurs, and by the mid-20th century, there were a substantial number of photography studios across West Africa. When the images in McKinley’s collection move away from European photographers towards African ones, their aesthetic changes as well. Early photographs of African women portray them not only as exotic, but also in a highly sexualized, even overtly pornographic way. These were to be brought back to Europe to reinforce the colonial narrative of Africans as the Other, and to propagate the sexual fantasy which stems from such othering. However, when African photographers began portraying female subjects, they did it in a much more self-assertive, celebratory way. In these portraits, the subjects assume a level of agency that was not seen before. With locals behind the camera, the gaze of the sitter, firm and confident, works to reclaim African identity and shed the colonial narrative of othering. These women appear more comfortable in front of the camera, and through their intricate fashions and strong eye contact make a proud assertion of their African culture. The legacies of empire without a doubt remain, but these images from an independent Africa look noticeably different from their colonial predecessors.

Untitled, 1939-45. Courtesy Bloomsbury

McKinley’s collection thus provides a refreshing new look at the visual history of African women. In choosing to collect images that exclusively contained female subjects, we are given a new, more in-depth look at the history of women on the continent and can trace the way visual narratives change and adapt with the times, especially in the context of decolonization. Rich with anecdotes and untold narratives, The African Lookbook is a valuable and exciting trove of feminine history on the African continent.

The African Lookbook can be purchased at Bloomsbury.