Exhibition Review: Off the Record at Guggenheim

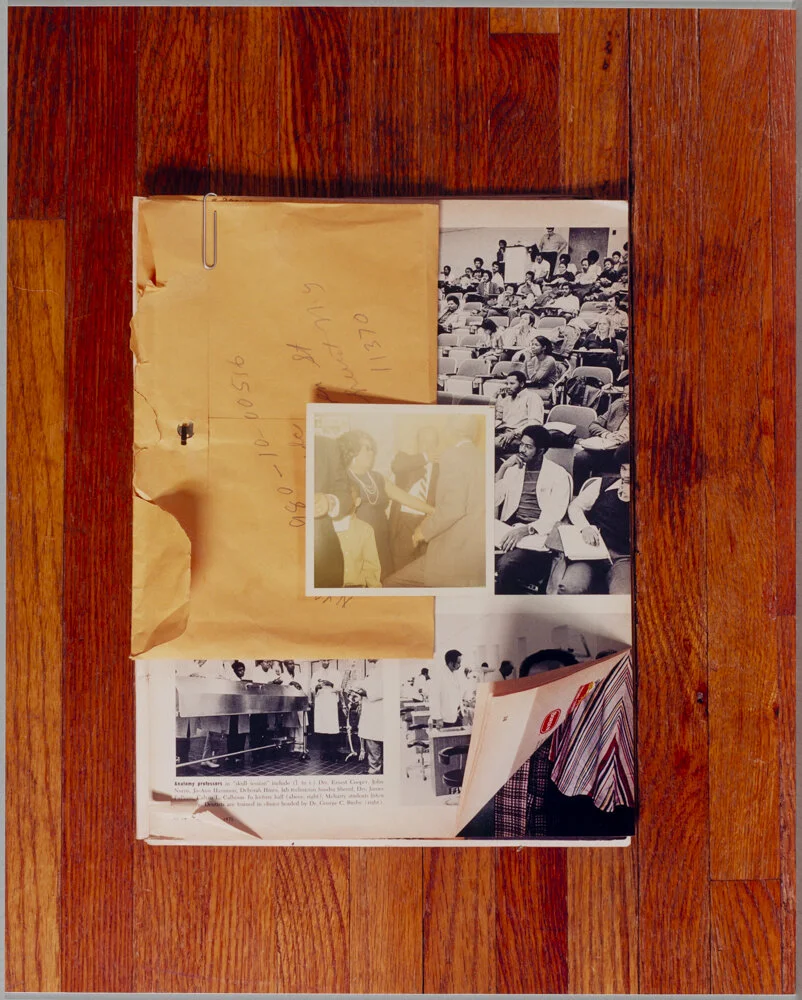

Leslie Hewitt, Riffs on Real Time (3 of 10), 2006–09. Chromogenic print, 30 x 24 inches (76.2 x 61 cm), edition 5/5. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Purchased with funds contributed by the Photography Committee 2010.55. © Leslie Hewitt

Text by Trevor Bishai

Copy Editor: Maggie Boccella

Photography has long been appreciated for its appeal to objectivity and truth. When daguerreotypes, cameras, and film replaced the painter’s hand as means of documenting real life in images, it was widely believed that photography could usher in a new era of fidelity to facts in reportage and narrative. But this assumption falters in many ways. Notwithstanding the advent of digital imaging technology which can fundamentally alter an image, photography has always been a subjective art, allowing the photographer to tell a narrative as biased and as partial as fiction. In its latest show, Off the Record, the Guggenheim Museum reinforces this view by featuring artists that have made direct challenges to the purported authenticity of photographic records. Accomplished in several ways, each of these works prompts us to examine the many fraught assumptions we make about official records and documentation.

The exhibition begins with a work by Sarah Charlesworth entitled “Herald Tribune: November 1977” (1977). A series of twenty-six chromogenic prints, the images show all the front pages of an international newspaperover the course of a month—but with all the text masked out. What is left is a scattered array of photographs from each of the articles and the newspaper’s nameplate. By stripping the newspaper of its text, Charlesworth forces us to read the newspaper as a photo essay, and the resulting narrative is steeped in critique. The images, which include photographs of world leaders, violence, destruction, and conflict, highlight the prevalence of war, militarism, empire, and white male hegemony in the news cycle. By replacing the superiority of language with visual representations, Charlesworth exposes the underlying inhumanity and even barbarism that has come to dominate our modern world. Furthermore, photography becomes an instrumental tool for the artist’s critique, as it tells a supposedly more authentic story than the text. Thus, Charlesworth makes not only a pointed assessment of the modern world, but emphasizes the capability that visual narratives have for making such a critique.

Sarah Charlesworth, Herald Tribune: November 1977, 1977 (printed 2008). Twenty-six chromogenic prints, 23 1/2 x 16 1/2 in. (59.7 x 41.9 cm) each, edition 2/3. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Purchased with funds contributed by the Photography Committee 2008.50. © Sarah Charlesworth

Another similar mode of critique is at work in Hank Willis Thomas’ “Farewell Uncle Tom,” taken from his series Unbranded: Reflections in Black by Corporate America, 1968-2008 (2005-08). In this series, Thomas removed all the text and logos from eighty-two commercial advertisements made between 1968 and 2008, which were targeted at the growing Black middle class in America. Stripping the images of all their textual accompaniments, Thomas reveals telling imagery of corporate America’s stereotypical understanding of Black culture. In these images, highly adorned African American individuals look directly into the camera with sly gazes, holding selections of unbranded beauty products, clothes, and cigarettes. Here, the consumer good is not the only thing commodified, as the image of the Black individual is highly oversimplified and objectified, exposing the inauthenticity of advertising in the context of the “Black is Beautiful” movement.

Hank Willis Thomas, Something To Believe In, 1984/2007. Chromogenic print, image: 30 1/8 x 21 1/2 in. (76.5 x 54.6 cm); frame: 36 9/16 x 27 15/16 x 2 in. (92.9 x 71 x 5.1 cm), edition 5/5. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Purchased with funds contributed by the Photography Committee 2011.13. © Hank Willis Thomas

In both Charlesworth and Thomas’ work, the photograph assumes the dual role of subject and medium. By appropriating images from external sources and stripping them of all their unnecessary additions, the photographs themselves become the subjects of their work, not only the medium in which the work is presented. Since the medium of photography is the subject, it has a story to tell—the stripped photographs create a narrative which is seen as more authentic or genuine than the way in which they were presented in their original form. In order to make their critiques, Charlesworth and Thomas return to the bare, unadorned form of the image. Their critiques are thus immanent in the images they appropriate, and a more authentic redress of the “record” only requires the removal of some additional media.

Lorna Simpson, Flipside, 1991. Gelatin silver prints and engraved plastic plaque, diptych, 51 1/2 x 70 in. (130.8 x 177.8 cm) overall, edition 2/3. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Purchased with funds contributed by the Photography Committee 2007.32. © Lorna Simpson

But not all of the works in the exhibition follow this pattern. Instead of removing things in order to convey an alternate narrative, several artists add or affix things to their appropriated images. In these artist’s eyes, some “records” are so misconstrued that they require addenda to be rectified. Two of Carrie Mae Weems’ works assume this process—“You Became Mammie, Mama, Mother & Then, Yes, Confidant—Ha” (1995) and “Descending the Throne You Became Foot Soldier & Cook” (1995). To make these, Weems appropriated daguerreotypes of enslaved Africans taken by Louis Agassiz, which were used to advance pseudo-scientific theories about social Darwinism. But instead of just laying bare these images, she applies a red tint to each of them and etches the eponymous text on the enclosing glass. The images’ narratives have now been entirely transformed through visual addenda—the red tint symbolizing coloration and the text granting agency to the descendants of these enslaved individuals. In reclaiming the narratives of these images with her own additions, Weems reminds us of our perpetual re-interpretation of historical records across time.

Sara Cwynar, Encyclopedia Grid (Bananas), 2014. Chromogenic print, 40 x 32 in. (101.6 x 81.3 cm), A.P. 1/2, edition of 3. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Purchased with funds contributed by the Photography Council 2016.50. © Sara Cwynar

Off the Record thus examines the process of reinterpretation in several ways. Nearly all of the works from this exhibition involve appropriated images, which highlights the way photography can become a subject as well as a medium. Photography has always been a medium, but through the historical re-examination of photographic records, it becomes a subject. The exhibition thus prompts us to be highly critical of and perceptive to the hidden narratives in mass media, and convinces us once more to reject the idea that photography is inherently an objective medium.