Photo Journal Monday: Tony Chirinos

©Tony Chirinos

For the span of seven years, I have photographed San Andrés people, architecture and it’s rich tradition of Cock fighting. San Andrés Island of Colombia is the home to three fighting rings; this small island has a rich tradition of cock fighting, which comes from its Spanish and Portuguese ancestry and from its influence coastal cities of Cartagena and Santa Marta. I learned of San Andrés through my ex-wife who shared with me her experience of life on the island as a young adolescent. Her stories spurred my desire to visit the island and eventually the first journey was set, and my love affair with San Andrés began.

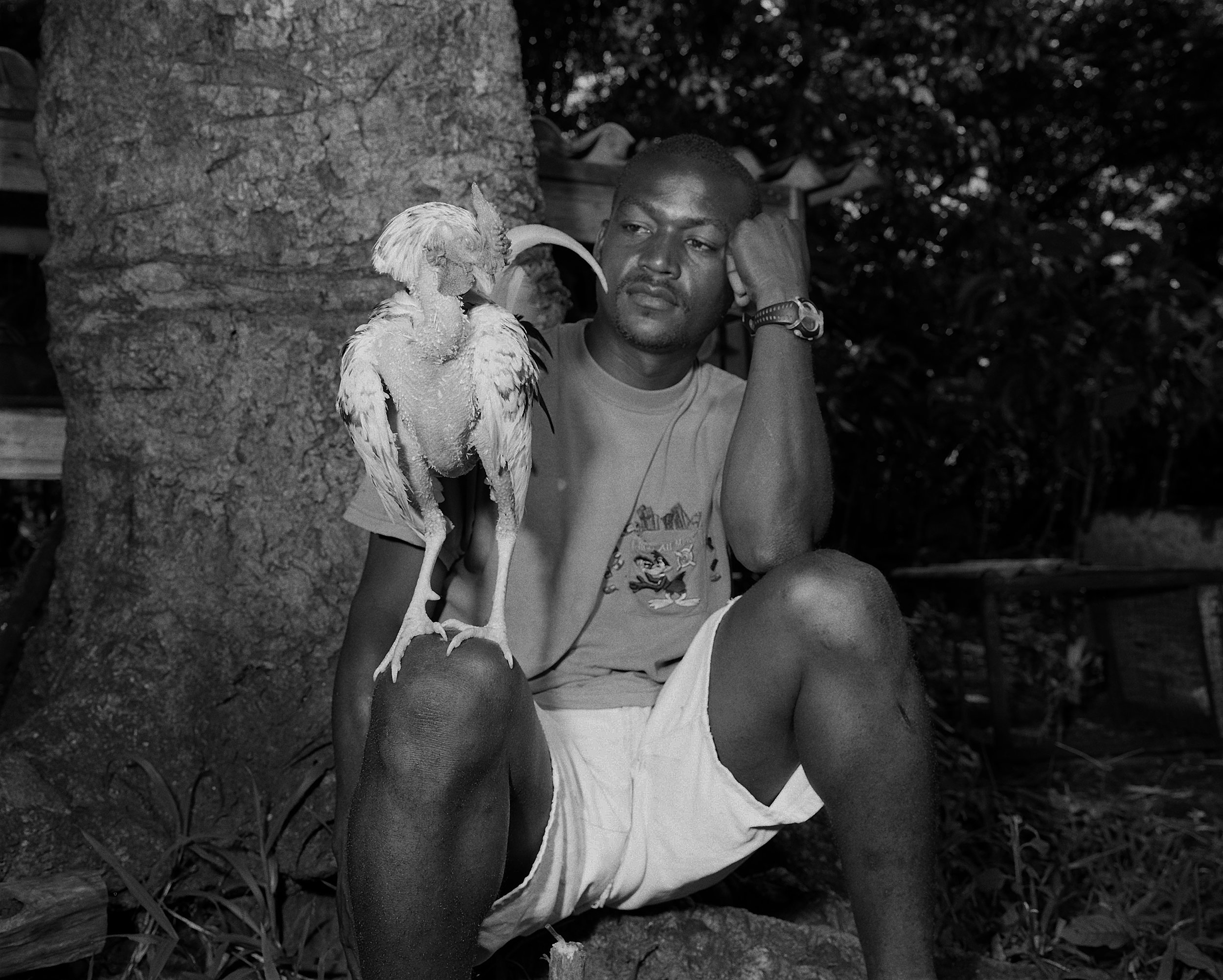

The photographs from this series entitled, “Cocks” were made during short frequent visits to the Island. This site-specific project depicts what I called a double portrait of fighting cocks. At first glace you see a rooster who embodies personality and at the same time a stage is apparent which references the world that surrounds it. Using my camera as an ambassador, I am privileged to explore the tradition of cock fighting, learn about the handling of roosters, and consequently integrate myself socially to an exclusive community.

©Tony Chirinos

I first heard about the tradition of roosters fighting as a child, listening to my father’s stories of his cock fighting adventures in Cuba. One of his tales was about his friend Julio (El Chino) Chane, a man who cared for his roosters even more than his own family. According to my father, Chane’s family often went to bed hungry because he would spend money on the roosters’ feed and vitamins rather than on food. Years later, I discovered a short story with a similar plot, “No One Writes to the Colonel” by Gabriel Garcia Marquez, about a poor couple, whose son was killed in a civil war leaving behind a champion rooster. The family is conflicted because they do not know whether to sell the bird right away to make ends meet, or to fight the bird and stake everything for the possibility of becoming rich. I wanted to experience first-hand the essence of these stories.

I am intrigued by the entire sub-culture of cock fighting, which considers this event a serious sport. When I began this project, my aim was to first learn the rules and regulations from a primary source by becoming acquainted with the islanders. One player who greatly influenced my perception of cock fighting was Wolly Thime, an avid participant admired by all in this circle of fighting roosters on San Andrés. Wolly owns over seventy fighting roosters all considered an extended part of his family. Each cock has a particular name such as El Machetero, Nelson Mandela, Coño and La Virgen. Naming the birds is a ritual event, it occurs during the debut bout where the bird displays characteristics associated to warriors which then the owner can extrapolate from in naming the bird. Wolly Thime exudes pride as a successful bird owner and breeder and his roosters directly or indirectly reflect this attitude.

In order to better understand the spectator’s perspective, I spent most of the time watching the fights, the breeders and the ritual of bird grooming. This made a great difference in the creation of this project because I integrated myself better within the environment and my appreciation of the subject heightened. My presence with the camera and all its’ accessories has not been unwelcome; on the contrary, I feel accepted by the entire cock fighting community. In my photographs I create a rich visual quality and an appearance of depth through a technical innovation of a bracket with multiple flash heads. The projects that I create and the pictures produced from these projects can be consider as having a documentary style referencing the history of photography. In this project I reference the Teutonic affection for sorting and cataloging depicted by the portraits of August Saunders, and the photo reproductions of crime scene images taken in New York and Paris in the 19th century. My portraits of the fighting cocks evoke the hidden horror of the spectacle, which is mentally produced by the individual viewer.

My goal with the project is to produce images that respect the cultural tradition of Cock Fighting in San Andrés without imposing a westernized ideology concerning the cock fighting practice. This attitude allows me to pay close attention to the birds, the bird handlers and the ritual of bird grooming. In this way, I am uncovering through a visual understanding the meaning of this sub-culture, which is an important part of my Hispanic family heritage.

©Tony Chirinos

©Tony Chirinos

©Tony Chirinos

©Tony Chirinos

©Tony Chirinos

©Tony Chirinos

©Tony Chirinos

©Tony Chirinos