Time's Palette: Interview with Bill Viola

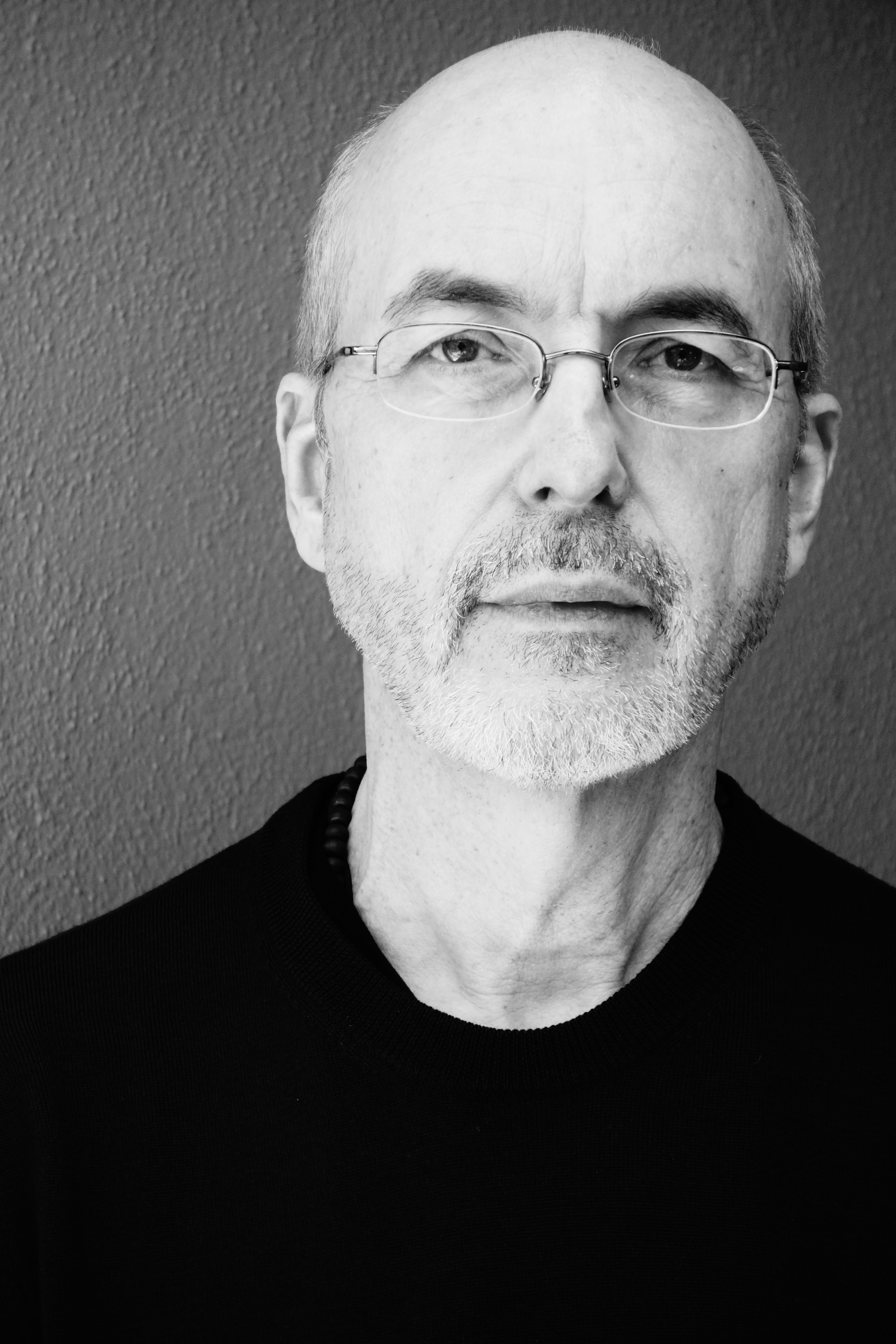

Image Above: Portrait by Paul Rusconi, Los Angeles, April 2014. All following images from Bill Viola, 2015, published by Thames & Hudson.

“Between How and Why.” (in: Bill Viola. “Reasons for Knocking at an Empty House. Writings 1973-1994.” Edited by Robert Violette in collaboration with the author. Thames and Hudson Ltd, London in association with the Anthony D’Offay Gallery, London, 1995, pp. 256-257.) First published as a statement for the catalogue Medienkunstpreis (Karlsruhe, Germany: Zentrum für Kunst und Medientechnologie, 1993) Courtesy: Bill Viola Studio.

The technologies of the optical image (photography, cinema, video) are machines for the close of the machine age. They are machines that produce content, that have as their product the direct imprints of the outside world. They give us the world back, and for this they are much more profound and mysterious than people realize. By nature they are instruments not primarily of vision, but of philosophy in an original ancient sense. Looking at the videotape recorder, it is difficult to realize that this machine, this object, comes from the earth. The metals and plastics that comprise its physical mass are all earth materials. They come from the ground. Even the electricity that activates it is a fundamental element of the natural environment. The history of much of human culture, particularly in the Western world, has centered on the development of the material. The contemporary electronic technologies of video and computer are simply the most recent stage of this evolution. Historically in the West, the work of Isaac Newton, and the scientific revolution that followed him, greatly accelerated the emphasis on the material. His discoveries and new approach shifted the inquiry into the nature of the world from religious/philosophical to scientific speculation, from emotive affinities to material causes, from empathy to reason: the apple now falls not because it desires to be at its proper resting place, the earth, but because a physical force called gravity pulls it there; the celestial becomes mechanical, and the primary mode of questioning the world becomes not why, but how. Today, at the close of the twentieth century, we are finding that questions of “how” are not enough to carry us forward through the millennium. The crisis today in the industrialized world is a crisis of the inner life, not of the outer world. It is focused on the individual, and on the confusing mix of signals and messages swirling around us that do not address a human being’s fundamental need to know and live the “why” of life. Talk of machines, technologies, capabilities, costs, markets, infrastructures, offers no guidance and is inadequate and irrelevant to the development of our inner lives. This is why art today, traditionally the articulation and expression of the “why” side of life, is now so important and vital, even though it remains confused and inconsistent in its response to the new demands and responsibilities placed on it in this time of transition. The new technologies of image-making are by necessity bringing us back to fundamental questions, whether we want to face them or not. The development of schemes for the creation of images with computers is an investigation into the structure and fabric of the world we observe and participate in. Spend time with a video camera and you will confront some of the primary issues: What is this fleeting image called life? Why are we here sharing the living moment, a moment that is past yet present? And why are the essential elements of life change, movement, and transformation, but not stability, immobility, and constancy? Faced with the content of the direct images and sounds of life in one’s daily practice as an artist, questions of form, visual appearance, and the “how” of image-making drop away. You realize that the real work for this time is not abstract, theoretical, and speculative - it is urgent, moral, and practical. Responding in an adequate way to the questions of “why” demands a new balance between the emotions and the intellect, and a reintegration of the emotions, along with the very human qualities of compassion and empathy, into the science of knowledge. Our work today as artists is not about describing the arrival at and possession of a goal, but instead it is about illuminating the pathway. It is not about a system of proofs and declarations, but a process of Being and Becoming. Media art, in its possession of new technologies of time and image, maintains a special possibility of speaking directly in the language of our time, but in its capacity as art, it has an even greater potential to address the deeper questions and mysteries of the human condition. This is the challenge to the media arts at the turning point of the century and the passage into the millennium that lies just before us.

Image Above: ©Bill Viola, Martyrs (Earth, Air, Fire, Water), 2014 (installation view). Duration: 7:15 minutes Executive producer, Kira Perov Performers: Norman Scott, Sarah Steben, Darrow Igus, John Hay. Photo: Peter Mallet.

MUSÉE MAGAZINE: When I was speaking with you at your opening, you mentioned that you’ve been returning to your old notebooks, and that you wanted to revisit your old work. What prompted you to revisit your past catalogue?

BILL VIOLA: My notebooks are filled with ideas for new works. One or two will surface as I scan them from time to time. Sometimes an idea appears in my notebooks several times over the years in slightly different forms, until the work is finally ready to be created.

MUSÉE: Your recent exhibition of “Inverted Birth” (2014) at James Cohan Gallery is reminiscent of “Emergence” (2002, commissioned by the J. Paul Getty Museum)—do you see it as a continuation, and do you often see later pieces as continuations of your earlier work? Or an elaboration, perhaps?

BILL: Over the years, I continue to explore the profound themes of human existence, life, death, and their mysteries. The same questions are found in all my works, just expressed in new ways.

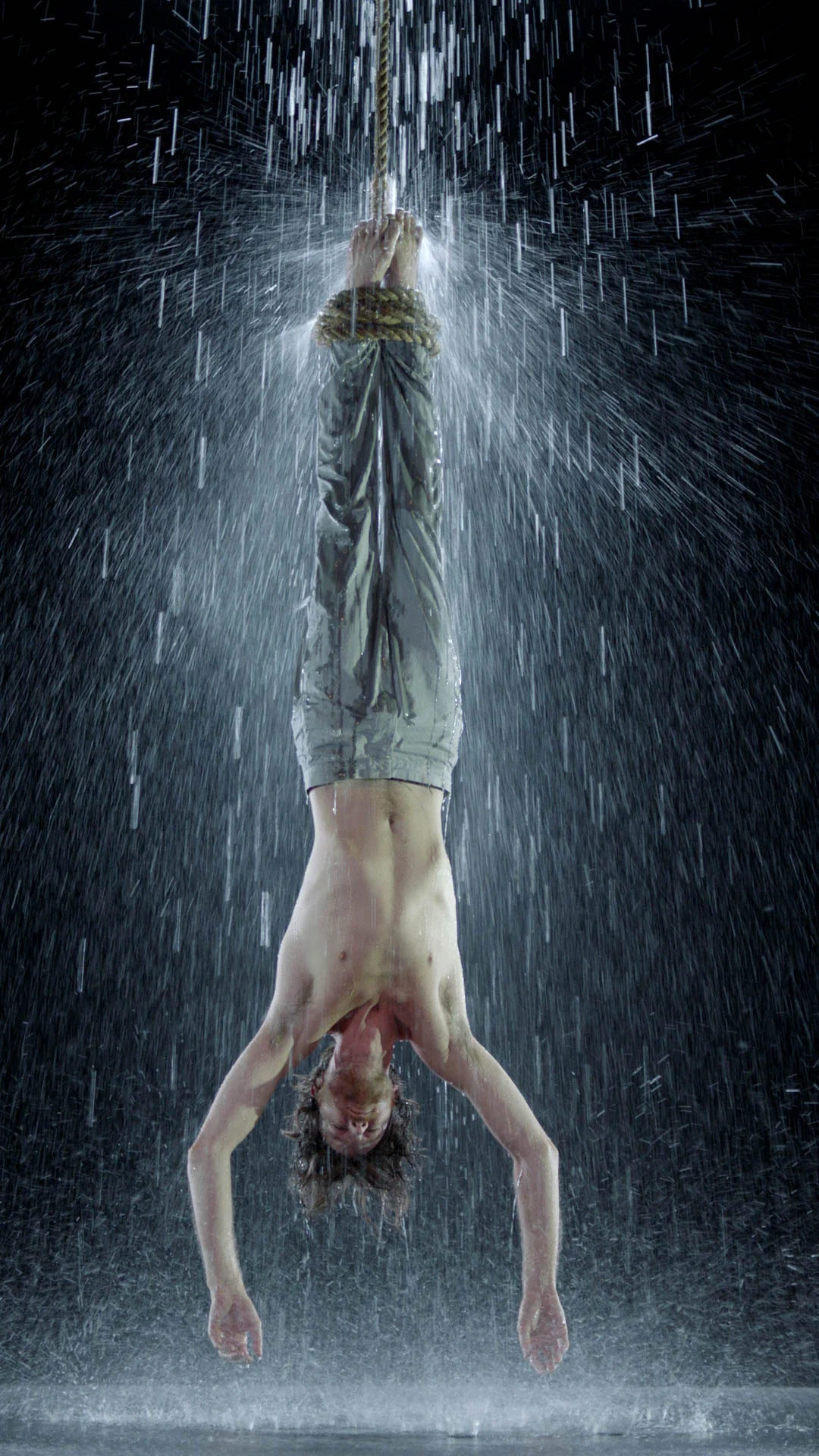

These two works you mention contain a paradox–they somehow represent birth and death at the same time. In “Emergence”, a young man rises from a watery cistern as in a kind of ascension, he is alive and yet he is also dead. “Inverted Birth” depicts a series of violent actions run in reverse, as if the person is awakening from the dead, and yet his transformation is also a birth.

Image Above: ©Bill Viola. Water Martyr, 2014. Color High-Definition video on flat panel display, 42 3/8 x 24 1/2 x 2 5/8 in. (107.6 x 62.1 x 6.8 cm), 7:10 minutes, Executive producer: Kira Perov, Performer: John Hay

MUSÉE: Spirituality and theology are two major themes in your work. How did your fascination with that genre start?

BILL: Spirituality is not a genre, it is a lifelong experience, a search for a path, or some answers… Theology per se is not really part of this search nor part of my work. I have used some religious metaphors in a few of my pieces (“Emergence” is one of them), but religious art is overwhelming in its representation of the emotions and the mysteries, and the artists who created these works were extraordinary in their skills. It is impossible to ignore the Renaissance, for example, or Orthodox icons, or Greek sculptures of the gods.

MUSÉE: You’ve mentioned that “emotion is a kind of movement”—how do you believe the medium of film best captures emotion?

BILL: A work that was first shown at MoMA in New York in 1987, Passage, takes 7.5 hours to unfold. The tape that was edited for this piece is 23 minutes long, but the playback machine plays it at 1/16th speed, so we see one frame at a time. The images are of a 4-year-old’s birthday party, and when slowed down and “stretched” so much, still contain the essence of the emotions that these children are experiencing. This way, this delightful experience is held for longer, something that all of us have wanted to do, to stop or slow down time in order to capture the moment.

Image Above: ©Bill Viola. Inverted Birth, 2014, Video/sound installation, Color high-definition video projection on screen mounted vertically and anchored to floor in dark room; stereo sound with subwoofer (2.1), Projected image size: 16 ft 5 in. x 9 ft 3 in. (5 x 2.81 m), 8:22 minutes, Executive producer: Kira Perov, Performer: Norman Scott.

MUSÉE: In your talk “The Movement In The Moving Image” at UC Berkeley (2009), you mentioned that, when making art, you have a very clear image in your head that you want to create in reality. Do you make visual modifications in the process of creating your videos, or does it usually not deviate far from your original ideas?

BILL: My ideas come in different ways. Sometimes I see the whole piece at once and it is a matter of filling in the details while shooting. Often, however, the “whole piece” is not the end of it, but other parts happen in the making that resolve the work and give it depth. Other times I need to develop an idea to bring it to life. Performers also bring a level of collaboration that can develop the idea. My longtime partner Kira Perov also assists in helping with creative decisions.

MUSÉE: When you’re working on a project, what comes first: the technology or the concept? How does technology influence ideas, and, conversely, how do ideas influence technology?

BILL: I have been very fortunate that technology and my work have had a parallel development, allowing me to be constantly expanding my palette. In some cases the idea for a piece comes before the technology is ready, and then I am pushing its limits. Sometimes the invention of a piece of equipment inspires the work, as with the advent of flat panel screens that could be mounted on a wall. The first thing I did was to turn them vertically, then I was able to make video portraits and do a study of the emotions, the “Passions” series. Using these tools has allowed me to extend and expand my vision, and continue exploring the inner essence of the world around me.

Image Above: ©Bill Viola. Inverted Birth, 2014, Video/sound installation, Color high-definition video projection on screen mounted vertically and anchored to floor in dark room; stereo sound with subwoofer (2.1), Projected image size: 16 ft 5 in. x 9 ft 3 in. (5 x 2.81 m), 8:22 minutes, Executive producer: Kira Perov, Performer: Norman Scott.