The Art of Profiling: Adam Broomberg & Oliver Chanarin

A Discussion of Adam Broomberg & Oliver Chanarin's SPIRIT IS A BONE (Mack 2016) by Arthur I. Miller

Portrait by Artists. All images of Sprit Is A Bone, by Adam Bromberg & Oliver Chanarin published by Mack. ©Adam Broomberg & Oliver Chanarin 2015 / Courtesy of MACK

In the 21st century art itself along with such concepts as aesthetics has undergone radical transformations. Not unexpectedly this came about from the fusing of art with science and technology into what I call in my recent book, Colliding Worlds: How Cutting-Edge Science is Redefining Contemporary Art,” a “Third Culture,” from which has emerged an “artsci” which I predict will eventually be referred to simply as “art.” This avant-garde has come to fruition in our Age of Information, the Age of Big Data. In their stunning book, Spirit is a Bone, the British-based photographers Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin look at what happens when technology and big data fuse with photography. The first two hundred pages are made up of portraits on the right-hand page with the subject’s profession on the opposite page. Then follows thirty pages of text from a conversation between the photographers and Elyl Weizman, professor of Spatial and Visual Cultures at Goldsmiths, University of London.

Bloomberg and Chanarin’s theme is surveillance art, a medium spun out of surveillance methods ratcheted up with 21st century technology - video-recording devices, closed-circuit television and digital cameras hooked up to hard discs. London is one of the most heavily surveilled cities where cameras are constantly recording.

Image Above: ©Adam Broomberg & Oliver Chanarin 2015 / Courtesy of MACK

Bloomberg and Chanarin have focussed on another highly surveilled society, President Vladimir Putin’s Russia. In a famous appearance on Russian television, the National Security Agency whistleblower Edward Snowden asked Putin whether the government spies on its citizens by monitoring their communications. Speaking to Snowden as one spy to another, Putin denied this, insisting that it was against the law in Russia.

Actually Snowden didn’t phrase the question precisely enough. Like England, Russia is highly surveilled with closed-circuit cameras and this is what most interests Broomberg and Chanarin. The reason is that a new generation of camera has appeared in Russia. Using an array of lenses it can shoot a face from different angles thereby eliminating shadows while providing enough data for a three-dimensional facial reconstruction. Broomberg and Chanarin explore the situation in which such cameras can possess sufficient clarity for facial recognition.

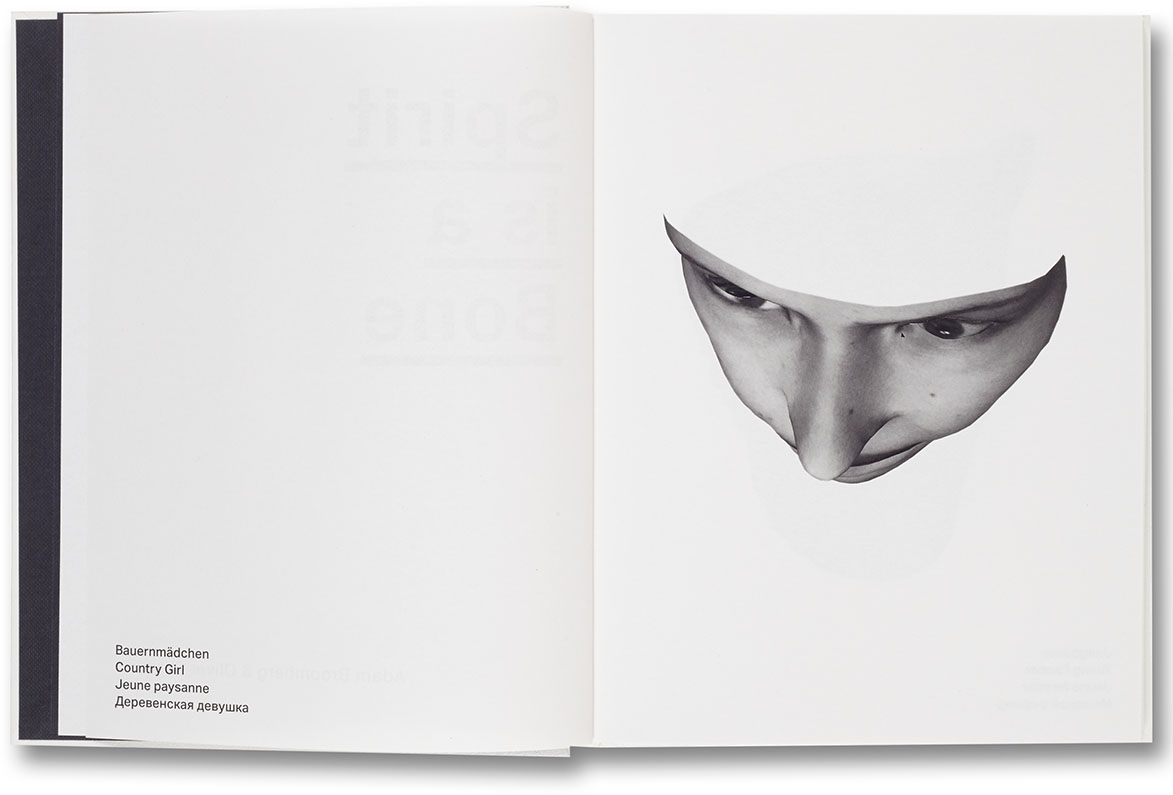

To do so they built a prototype of the new Russian surveillance cameras equipped with four lenses. Over 1,000 Muscovites volunteered as models for their photo ‘shoot’, including the Pussy Riot band member Yekaterina Samutsevich. The photographs are extraordinary. “What we’re seeing is the negation of that humanity: the digital equivalent of a death mask,” they write. The subjects are portrayed in black and white from above, below, profile and three-quarter view. The result is that there are no shadows in their portraits.

Bloomberg and Chanarin selected one of these angles, different ones for different people, and trimmed it in such a way as to display only the face as if it were lifted off the skull. It’s two dimensional but appears to have three. Expressions are bland because the subjects are assumed to have been unaware of being photographed and so are unposed, passive. On the facing page the subject’s profession appears but no names.

Image Above: ©Adam Broomberg & Oliver Chanarin 2015 / Courtesy of MACK

The book’s title is taken from Hegel’s The Phenomenology of Spirit, where he discusses the two pseudo-sciences, physiognomy and phrenology. In the former, facial expressions are critical and in the latter it is the materiality of the skull underneath that is supposed to reveal the essential truth about the subject. In Nazi Germany these two subjects cost millions their lives.

Today building up a person’s face from their skull, forensic anthropology, or facial recognition, is used to pass judgement on the subject only as regards whether the skull belongs to a murder victim or perhaps the murderer. Whereas facial marks from a knife or other weapon can heal, if deep enough they are forever embedded in the skull. Although DNA analysis can now identify a skeleton, what the person actually looked like is another matter. This requires adroit handiwork such as plotting contours when building up facial tissue. Sometimes the reconstructed facial tissue can be overlaid with a photograph of the alleged person for further verification.

The truth is in the bones, as Hegel argued. After all bones are unchanging even in death, unless chipped away for plastic surgery which is easily detected. What can we say about the link between the skull and what overlays it, the face?

What Broomberg and Chanarin have done in their book is to create an archive inspired by August Sander’s Citizens of the Twentieth Century. Sanders began it after World War I in Weimar Germany but was interrupted by the advent of World War II. It contains the faces of bankers, poets, revolutionaries, the unemployed, migrants and so on, often named. Sander’s archive was studied closely, read and reread, interpreted and reinterpreted. In Nazi Germany it took on a new and sinister meaning following the doctrine of Aryan supremacy effectively sentencing certain racial groups to death. Bloomberg and Chanarin “see disturbing parallels of this totalitarian regime in present-day Russia,” which is why they chose Russia as the stage for their project.

Bloomberg and Chanarin’s archive differs from Sanders in many ways. They never state names, only professions. One photograph has the caption “The Revolutionary.” The face belongs to the Pussy Riot band member, Yekaterina Samutsevich. What the state machinery sought in Sander’s photographs, as it did in Alphonse Bertillon’s ‘mug shots’ in Paris in 1879, was types, whether people who looked a certain way were Jews, gypsies, thieves, political agitators (aka revolutionaries), etc. Whereas Sander employed an 8x10 inch plate camera, Bloomberg and Chanarin used a camera purpose-built for facial recognition.

Image Above: ©Adam Broomberg & Oliver Chanarin 2015 / Courtesy of MACK

Nowadays photographs serve in the search for individuals rather than groups. Photo-id is required just about everywhere in order to identify an individual. At borders, such as airports, additional photographs are often taken. But these photographs are not a recourse to physiognomy – you are usually instructed not to smile. The photographs in this book go beyond a photo-id. Although two dimensional they appear to be wrapped like skin around a skull and so form a new sort of representation, which “returns us back to the [unchanging] skull, and the ‘truth’ underneath the face,” writes Elyl Weizman. In this way we return to a form of the phrenological principle of prediction, “of looking at various patterns to see the future,” says Weizman. However, he continues, the future is the domain of the algorithms whose grist are the big data sets that make up digital photographs.

Bloomberg and Chanarin’s work is a fine example of the fusion of art and technology giving rise to images never seen before. They are the product of more than art and technology moving ahead hand in hand. Rather these two disciplines are merged into a single discipline. This leads to a new aesthetic which is the sum of the visual image and the technology that produces it. Only through understanding this new technology can the work of art be most deeply appreciated.

-----------------------------

Arthur I. Miller is Professor Emeritus of the Philosophy and History of Science at University College London. His latest book is Colliding Worlds: How Cutting-Edge Science is Redefining Contemporary Art (W.W. Norton.

-----------------------------------