Paranoid or Paranormal?: A Brief History of Spirit Photography

A ghost is created through double exposure, 1932. © Frederick D. Ryder/Wikimedia Commons

By Andrea Farr

Discourse surrounding spirit photography has long been concerned with the veracity of the genre. The ability to capture human spirits on film seems like a stretch for the reaches of both art and science, but this practice has persisted for nearly two centuries, speaking to the age-old desire of humans to figure out what comes after death. Our curiosity is still a contemporary point of research—exhibitions such as The Perfect Medium: Photography and the Occult at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the recent Hilma af Klint collection Paintings for the Future at the Guggenheim diving head first into explorations of Spiritism and renderings of a world beyond our realm. Even more accessible and telling of our collective interest, a Google search of “ghost hunting” today will render millions of hits.

On this Halloween, but also seemingly every other day of 2018, the question of “Is what I’m seeing real?” haunts us in our current moment when distorted, decontextualized, and Goop-era logic often serves at the forefront of discovery and perceived truth. To honor the spookiness of today, we want to revisit the genre of spirit photography in light of these modern expectations and experiences of truth, and see how the evolving landscape of photography has impacted this practice of catching the dead on film.

An apparition in an abandoned Colombian mine, 2014. © EEIM/Wikimedia Commons

There is a particular tension in the way we attract, ingest, and process the information around us. While we are told to be cautious and critical of the things we read, hear, and see, we simultaneously have a way of seeking out the things we want to see, and we surround ourselves with information that makes this possible. This ideology is what lead the first recorded spirit photographer, William Mumler, an engraver from Boston, to surprising success with rendering images of the dead beginning in 1861.

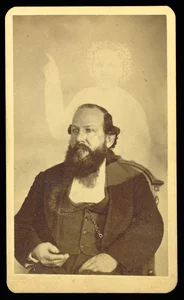

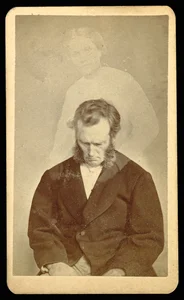

Portraits by William Mumler,

taken from 1862-1875.

© J. Paul Getty Museum

The spring of that year marked the start of the Civil War, which produced an unprecedented amount of American casualties, and as a result, a mass grievance of the American people and a deep desperation to reconnect with loved ones taken by the war. After the alleged discovery of an apparition, said to be his dead cousin, in the background of one of his photographs, Mumler was able to capitalize on the mourning population, and launch a career in spirit photography.

When we seek to see specific things, we surround ourselves with information to make it possible. As the war reached a record-high death toll, the American people sought ways to find evidence that their loved ones were still with them, and found a particular solace in photography’s ability to present itself as proof. Spirit photography soon rose as a trend that capitalized on global instances of devastation: in France after the War of 1870, and later in Europe after World War I.

French photographer Édouard Isidore Buguet captures a chair levitation, 1875. © Édouard Isidore Buguet/Wikimedia Commons

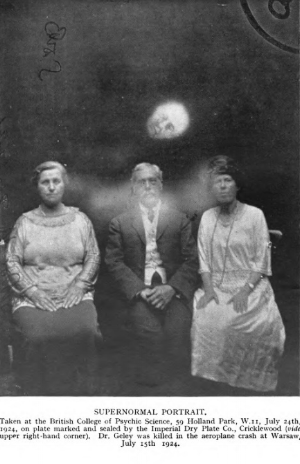

Stanley De Brath and the alleged spirit face of Gustav Geley, 1924. © Stanley De Brath/Wikimedia Commons

Although Mumler achieved great fame, the high-profile apparition of Abraham Lincoln appearing in a photo following his assassination eventually caused Mumler to be exposed as fraud after a series of publicized court trials. The works of spirit photography by others that followed were commonly discredited as careful acts of visual trickery, utilizing multiple exposures and combination printing to produce images of the supernatural. However, the genre persisted, and the topic of spirit photography was retained in Western dialogues by British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace and writer Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, French psychologist Charles Richet, and American philosopher William James, the founder of the still-existing and New York-based American Society for Psychical Research.

Suspected double exposure spirit photograph at Marshal Douglas Haig's funeral, 1928. © Wikimedia Commons

Photography itself rose out of a supernatural ideation—an unprecedented and, at the time, eerily accurate way of capturing reality. So much so, that when the medium began to be more widely practiced in the early 19th century, some feared a bit of their soul was consumed with every moment captured. In the beginning, photography was more science than art, cyanotypes and darkroom processes innately chemical, and photographs often employed for uses in documentation and preservation, rather than artistic expression.

Ectoplasmic, 2016. © JR Pepper

Exude, 2016. © JR Pepper

Spirit photography operates on the same platform of scientific photography; they both realize the medium’s ability to make previously invisible things visible to the human eye, whether it be parts of an atom, corners of our solar system, or paranormal presences. Now, present-day photographers consider this more deeply in the context of a malleable truth, utilizing similar techniques of centuries past to fabricate haunting presences and looming figures, and explore the desire to give form to our speculations of an afterlife. In her series Exquisite Spirits, JR Pepper uses multiple exposures to evoke the movement of a possession, or exorcism. Ellen Jantzen digitally manipulates her pictures to create a mystical and ephemeral experience from natural scenes.

Into the Unknown, 2013. © Ellen Jentzen

Threshold, 2013. © Ellen Jentzen

Our history of seeking spirit-filled images is a very self-revealing behavior. It speaks to the strength of our beliefs, and our desire to uncover the unknown—an unknown with very personal consequences. This phenomenon is pertinent to how we operate in our world today, when we are seeking a similar answer for what will come of us, some days the timeline feeling more imminent than others. We will proceed on our journey of developing a higher register for what we believe, but we will also continue, inevitably, humanly, to look for evidence to reinforce the things we wish to be true.