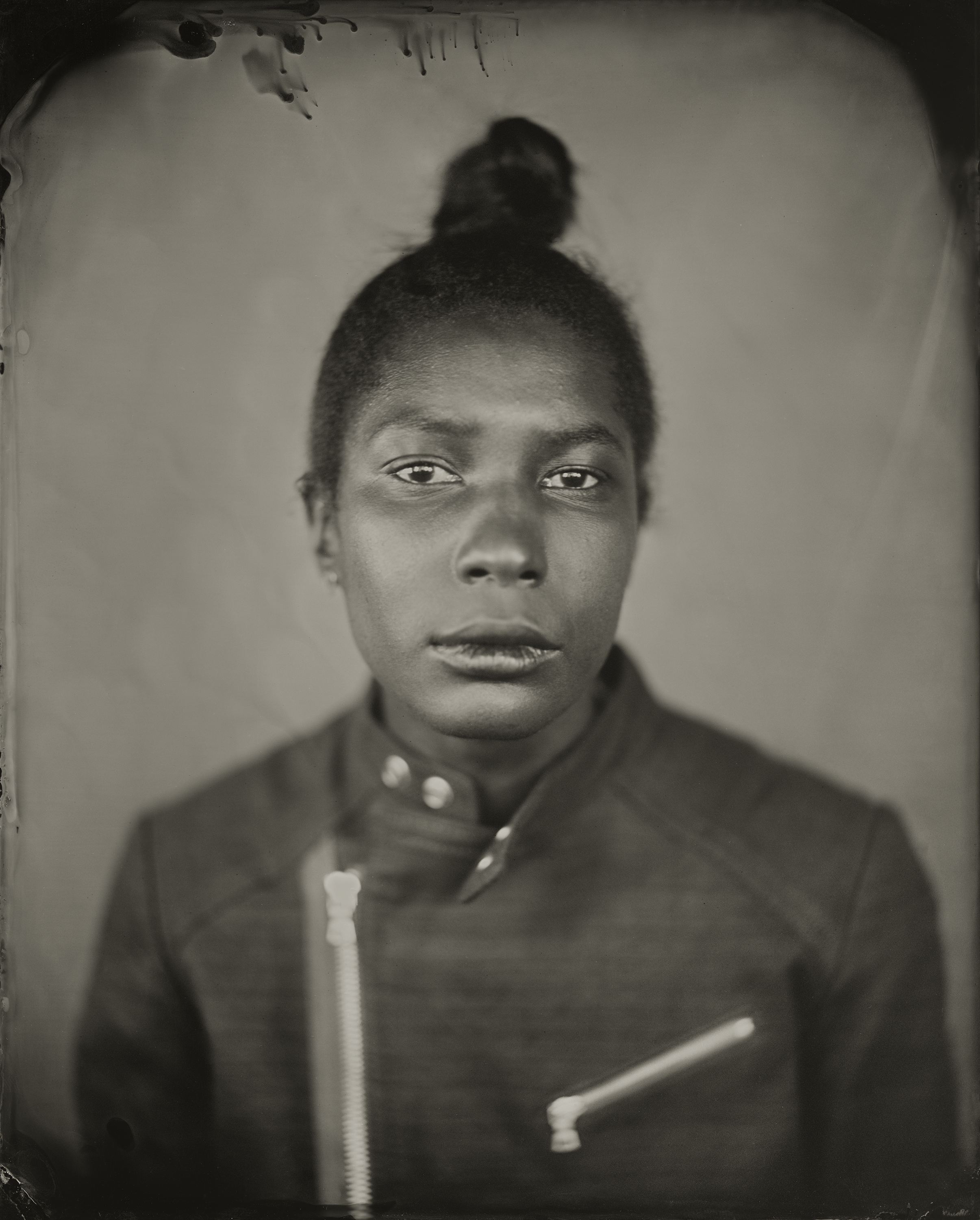

Woman Crush Wednesday: Keliy Anderson-Staley

© Keliy Anderson-Staley

Interview by Mamie Heldman

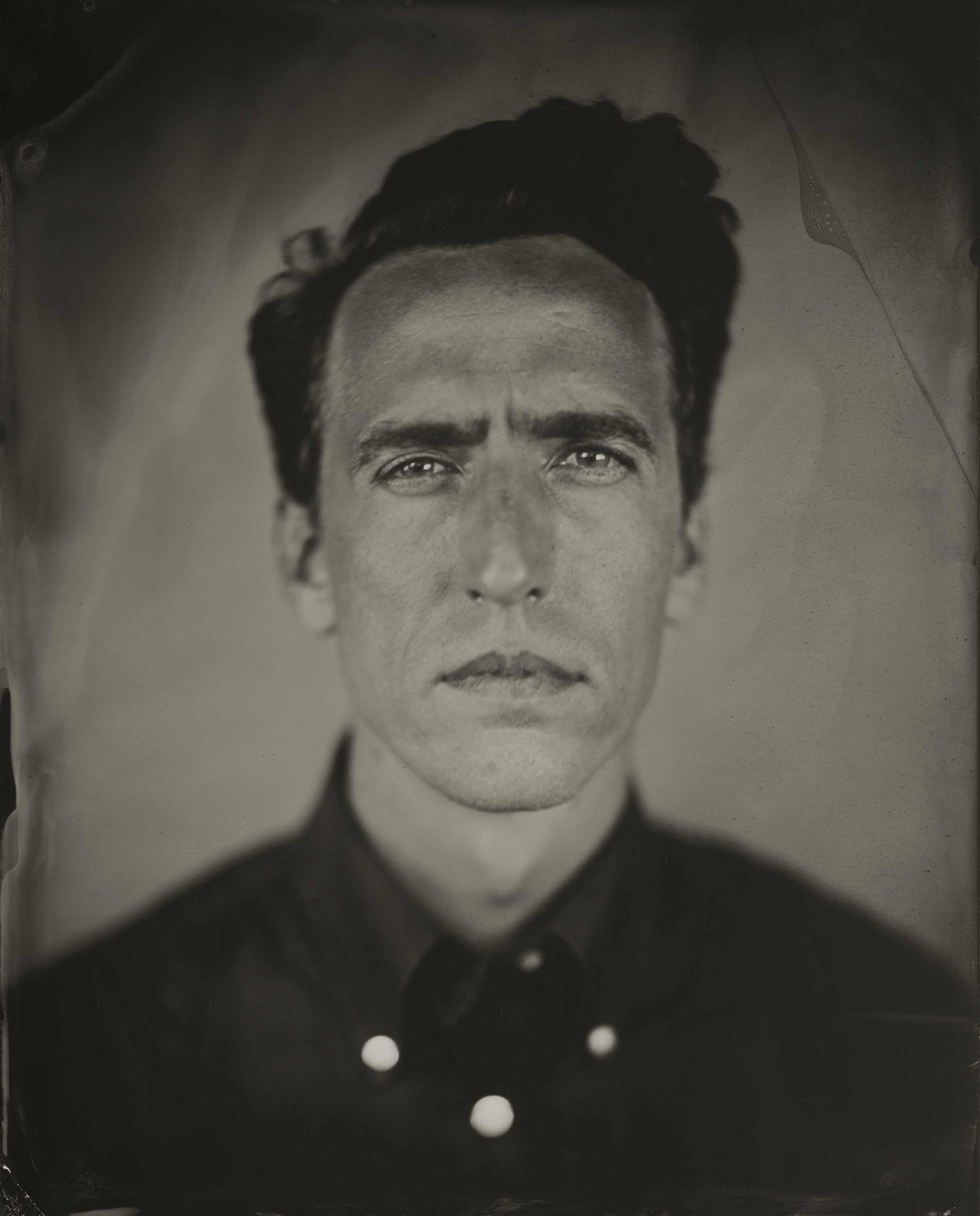

[Hyphen] Americans is a broadly diverse collection of tintype portraits by Keliy Anderson-Staley. Made with chemistry mixed according to nineteenth-century recipes, period brass lenses and wooden view cameras, each subject is identified by their first name only, aiming to collect the diversity of American faces and beg questions about identity and individuality, as it pertains to one's place in history.

You say you were raised off the grid in Maine. How has your background influenced the way you photograph and your chosen process of wet plate tintypes?

I did grow up off the grid. We lived in a cabin in the woods with no electricity and no plumbing, but we did have an outhouse and a hand pump for water. I actually didn’t start making tintypes until living in New York City, and my first studio was in Queens. It’s possible that I am a little more patient with an archaic process because of how I grew up. I was probably also predisposed to like art forms that have a degree of physical engagement, that are handcrafted. Living off-grid, so much of how we lived required the kinds of knowledge that used to be passed down but isn’t anymore. There is a lot to be said for a direct connection to a craft and to nature that comes right up to your doorstep. I appreciate having grown up how I did, but in my adult life, I prefer city living.

Because of your process, do you feel as if your photographs serve as living objects? If so, how do you think your audience interacts with them differently than if simply given a print?

I love beautiful prints, and I think they can have as powerful a presence as any other work of art. A tintype, though, can have a surprising solidity. I rarely frame them, so they are often hung floating on a wall. They become objects that way. They also have a surface that changes as you move around the room. Shifting light really affects how you see the contrast of the image. They can have a subtle luster that draws you in. One thing that distinguishes it from a print, though, is that it is the actual plate that was in the camera. There is no intermediate negative or printing process. It’s always seemed significant to me that the very same light that bounced off the sitter’s face passed through the lens and exposed the plate. That immediacy, to me, is the essence of photography. Also, because the plate size is the same as the exposure, and collodion has no grain, there is a crispness in the image that is almost impossible to replicate in a print. That having been said, there is also something powerful and jarring about a scanned tintype in a digital context. I often see people using my portraits of them as their profile pictures. The work lives in that way, too.

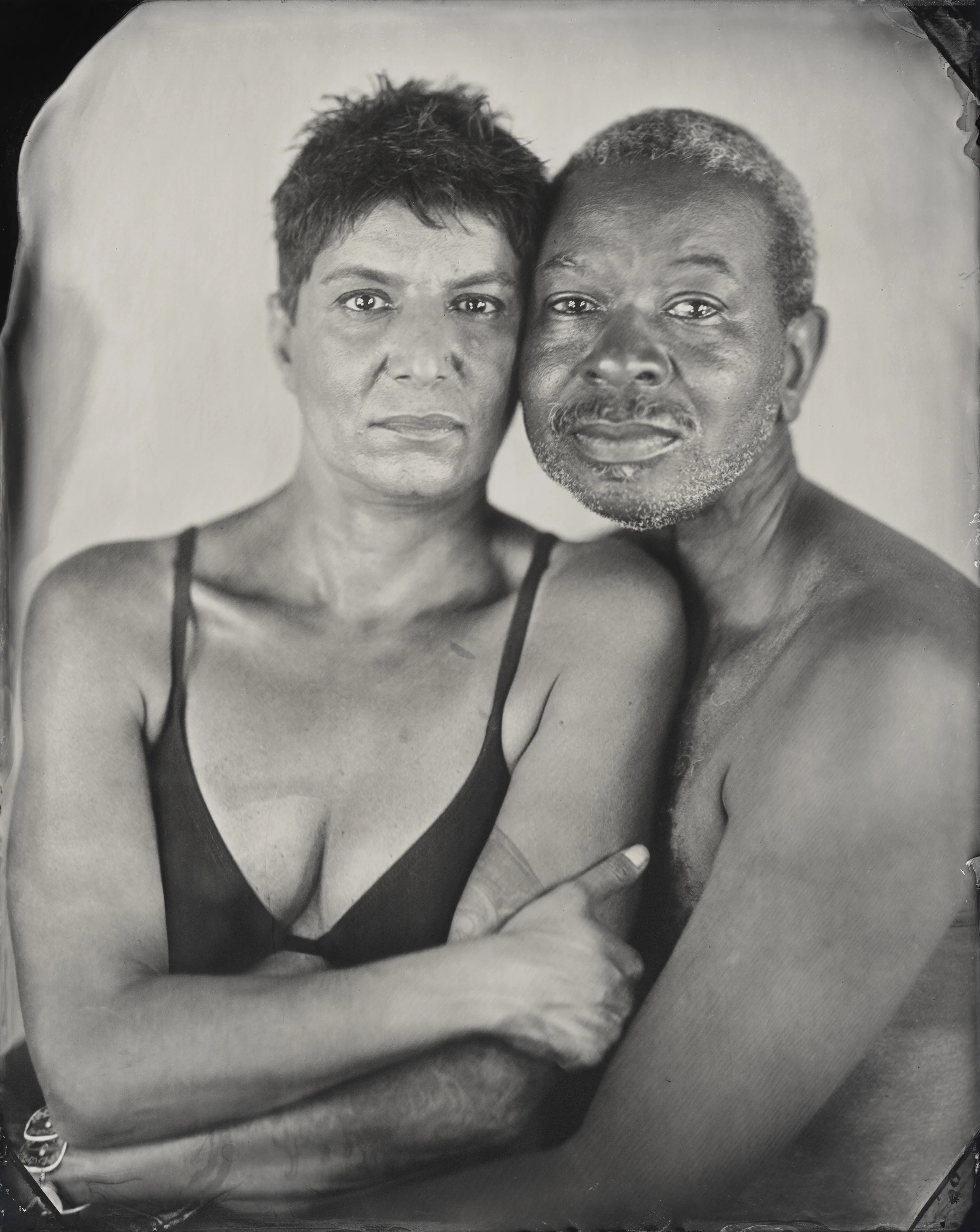

I love your portfolio entitled, “In the Same Frame.” The dynamics captured in your group portraits are subtle, yet striking. Group portraiture can be tricky. Can you talk about your experience working with couples and families together in one frame?

It can be hard to capture groups in a photograph. Anyone who has done it knows that there is always one person not looking in the right direction or who has a goofy expression. The long exposure of collodion is an added difficulty, as is the fact that I am using lenses with shallow depths of field. All the sitters need to be in the same focal plane, so I line them up in a rigid line. Similarly, with couples, I often have them sitting very close together, heads aligned, using each other’s body for stability as they hold the extended pose. I’ve embraced the awkwardness of group photos in this series. I think the fact that everyone looks slightly uncomfortable actually highlights the physical and emotional bonds that connect them.

Just recently, fifty of your portraits went up for exhibition in the Red Line Tunnel leaving the Cleveland airport, just in time for the Republican National Convention. These photographs are part of your larger body of work [Hyphen] Americans. How does portraiture serve as the best medium to convey what you perceive America to be?

I was commissioned to make portraits of Clevelanders, which were enlarged to 40 x 50 inches. Among my subjects were Cleveland area artists, writers, musicians. Cleveland is a very diverse city, more than 50% African-American. This project showcased this diversity while the whole world turned its attention to politics in Cleveland. So much of our election season is spent discussing racial and gender groups and their voting preferences. The status of immigrants, refugees, people of color, LGBT individuals, is constantly being contested in the public space of the campaigns. I think politicians forget they are talking about real people, not abstract concepts, individuals whose lives are impacted by policing practices or access to public facilities.

© Keliy Anderson-Staley. From Fifty Faces of Cleveland

A photographer shapes our perception through a portrait, but a portrait is ultimately of a very specific person in time and place. The sitter brings just as much to the equation, not the least of which is the accumulation of experiences in their face. I like that when the portraits are installed, they have a real presence, as if the person is in the room looking back at you, demanding to be seen. I don’t want to speak for anyone when I make a portrait of them, and I hope to leave space for them, through their expression and posture and gaze, to play a significant role in how they are perceived.

The Collodion process requires long exposure times and is highly technical, requiring a very specific approach. Do you feel that this effects or changes the opportunity for spontaneity during your sessions?

One thing I’ve always liked about collodion is that the long exposures mean that I capture the person over an extended period of time. I take a long time to set up the shot, and I may need to make several before I am happy. If it was a digital shoot, I might take several hundred. I hope to get four or five images per hour. So, I am not going for that surprise look, or some expression caught when the subject is off-guard. The images I make are in the history of formal portraiture, and I am definitely working within and against the history of that genre. There can be spontaneous moments, though—a sitter might settle suddenly into a pose, and I’ll exclaim, “That’s it! Don’t move!” Of course, they still have to go on and hold that pose for a number of minutes while I prepare the plate and make the shot. Maybe it’s a staged spontaneity? One thing that does happen, though, is that because of the length of the shoot, I get to really talk to people and get to know them. Even if I am only meeting them for the shoot, they often go on to become friends, and I’ll keep in touch with them for years.

You are currently living in Texas, teaching at the University of Houston. What has surprised you most about teaching and what have you learned most from your students?

There is a great art scene in Houston, and some really great artists come through and out of our program at the University of Houston. We are the second most diverse research university in the country, and that makes for a vibrant classroom with a lot of perspectives. There is so much for me to learn from their experiences, their understanding of this city and their generation’s take on political, environmental and cultural issues.

© Keliy Anderson-Staley.

Woman Crush Wednesday Questionnaire:

How would you describe your creative process in one word?

Messy.

If you could teach one, one-hour class on anything, what would it be?

Portraiture and power dynamics between the photographer, the sitter and the viewer.

What was the last book you read or film you saw that inspired you?

Voyage of the Sable Venus, a book of poetry by Robin Lewis.

What is the most played song in your music library?

I’ve been listening to a lot of NPR tiny desk concerts.

How do you take your coffee?

All day long.