Image above: © Denis Brihat, Pear, 1971, Courtesy Nailya Alexander Gallery, New York.

“The atmosphere here is fantastic!” gushes a florid white-haired man in a fawn overcoat. “Everyone is so welcoming!”

It’s Saturday May 23rd, Day 3 of Photo London. The vast halls of Somerset House are abuzz with people, most a couple of generations younger than the white-haired man. They’re in scarves and skinny jeans, pushing from gallery to gallery. Deals are brokered, sales are made. The excitement is palpable.

In parallel to the gallery exhibitions there is a fascinating programme of talks which is also a way of hearing from or about several artists whose work is not on show in the galleries.

On preview day Louise Clements, artistic director of Format and Quad, two major photography festivals in Derby, gives a talk entitled “On Collections”. It soon becomes apparent she’s not talking about big money collectors or how or what to buy but something much more interesting - artists who collect found images and use them to make something new.

Italian photographers Arianna Arcara and Luca Santese visited Detroit intending to take images of industrial blight but started finding photographs left in vacant buildings - polaroids, snapshots, police records, mug shots, many stained, crumpled or torn. They sorted through these ghostly remnants of lives lived, printed them and put them together in a book, “Found Photos in Detroit”. It’s a powerful document of the city as witnessed by its inhabitants.

Another artist Clements mentions, Thomas Sauvin, buys negatives by the kilo from an illegal recycling site in Beijing where they are waiting to be melted down to extract the silver nitrate. He has collected more than half a million, family pictures of people enjoying themselves at theme parks, weddings, funerals. He’s put them together to form an archival series, “Beijing Silvermine”, a fascinating portrait of thirty years of social change in China, from the first Kodak to the coming of digital in 2005.

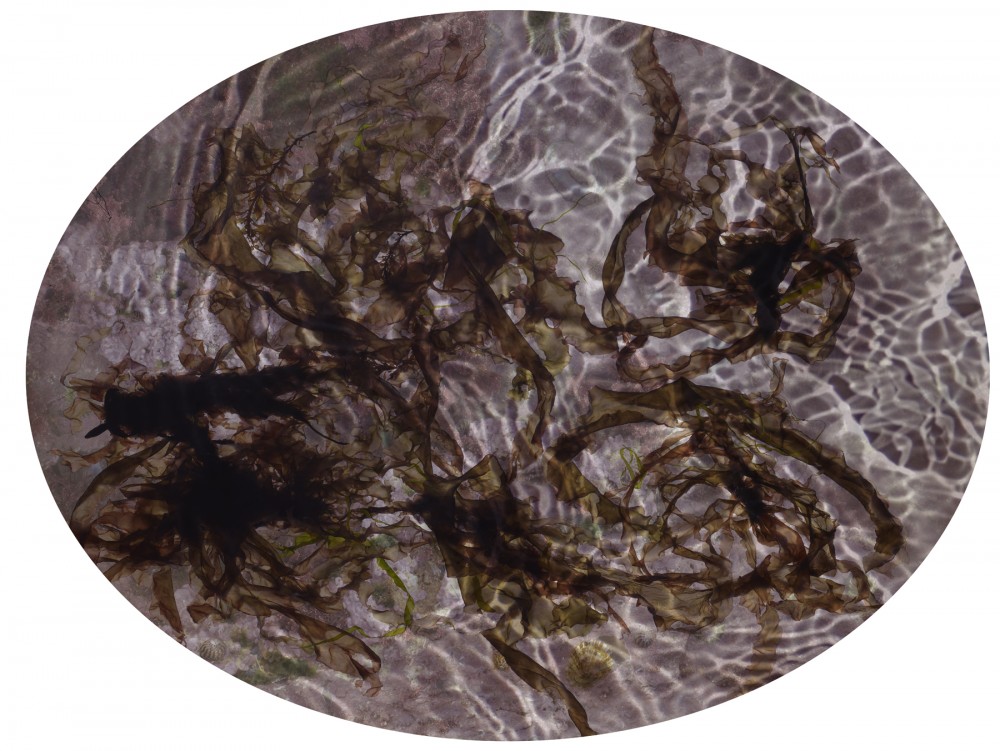

On Thursday Photo London flings its doors open to the public. I go to hear Susan Derges talking about her exquisite work. The image that encapsulates it shows droplets of water spilling across the picture with a blurry backdrop of Derges’ face behind. In each droplet is another tiny image of her face. Derges often works without a camera. She places photographic paper directly into the water of tidal pools on the north Devon coast and creates ethereal images, drawing the viewer inside this tiny world so that we look out of the water rather than onto it. Many of her works are on display at the Victoria and Albert Museum, a high accolade, and at Photo London are at the Purdy Hicks Gallery.

© Susan Derges, Tide Pool 27 May 2014, 2014, Courtesy Purdy Hicks Gallery, London.

© Susan Derges, Tide Pool 27 May 2014, 2014, Courtesy Purdy Hicks Gallery, London.

The next day Tom Hunter and Esther Teichmann discuss their work. Hunter recreates classical paintings in impoverished working class Hackney in London’s East End. One of his best known works riffs on Millais’s 1852 “Ophelia”. In place of Millais’s Pre-Raphaelite beauty, Hunter’s girlfriend floats in a murky pond with the industrial wasteland of Hackney rising behind. Hunter is the first photographer to have been offered a residency at London’s National Gallery, where his photographs have been displayed alongside reproductions of the pictures that inspired them - Vermeer’s “Girl Reading” next to Hunter’s update, “Woman Reading a Possession Order.” The photographs are witty and beautiful, gritty though the subject matter is. His works are at the Victoria and Albert and also at Purdy Hicks.

Esther Teichmann weaves evocative tales using ethereal images - plants, seaweed, naked women swimming - alongside video and story telling. Her work is at Flowers Gallery. For her as for all these artists photography is a way to make magic.

On day three the solemn corridors are heaving. Several photojournalists have assembled to talk about their work.

Chloe Dewe Matthews shows a memorable picture of a woman bathing in crude oil as a health cure at an Azerbaijani spa, a different perspective on this troubled part of the world. Fascinated to learn that World War I deserters were executed by their own side she photographed all 23 execution sites, from woods to abattoirs - a very different way of looking at World War I.

Edmund Clark is the only photojournalist to have been granted access to Guantanamo Bay. There he photographed the bland institutional-looking living quarters of both inmates and guards to provide a fascinating picture of the banality of everyday life here. There are no people in his images. We have become too ready to assume that a picture of a man with a big beard shows a terrorist, he explains. So he’s decided to leave ouyt the stereotypes and just show the homes.

American Lynsey Addario introduces herself as “just a traditional photojournalist”. She describes her adventures taking photographs in Iraq and Darfur and, fully veiled, in the Taliban camp. After 9/11, she went straight to Pakistan in search of the opposite viewpoint. Like all these photojournalists, she says, she wants to give a different perspective, tell the other side of the story, of those whose story is not told.

I’m excited to have the chance to see the legendary Sebastiao Salgado. He looks the part - a sinewy elderly man, very straight-backed, with a bronzed bald head and startlingly white eyebrows. His Brazilian accent only adds to the charisma. “I go alone to take photographs,” he says. “You are there, you are part of that place. Is a question of time, of patience, of dedication of your life to it. I’m not a photojournalist. Is my life.” Images from his awe-inspiring “Genesis” series form a separate exhibition in Somerset House.

That evening I go to hear Simon Schama, the renowned British historian and critic, discussing portraiture with Nadav Kander and Jason Bell. The two of them have photographed almost all the major figures of our time, famous and infamous, from Bell’s picture of Courtney Love stepping onto a tea table like a quasi Alice in Wonderland to Kander’s portrait of a sombre Prince Charles, ready to shoulder the responsibilities of kingship.

The three exchange banter. The aim of portraiture, says Schama, is “in one image to describe the totality of the character”. Bell comments that in that case the photographer’s job is to persuade the subject to show a little more of themselves. “I love photographing actors,” said Kander, referring to his portrait of Mark Rylance. “They realise that it’s not only about catching a likeness. It’s about the atmosphere.”

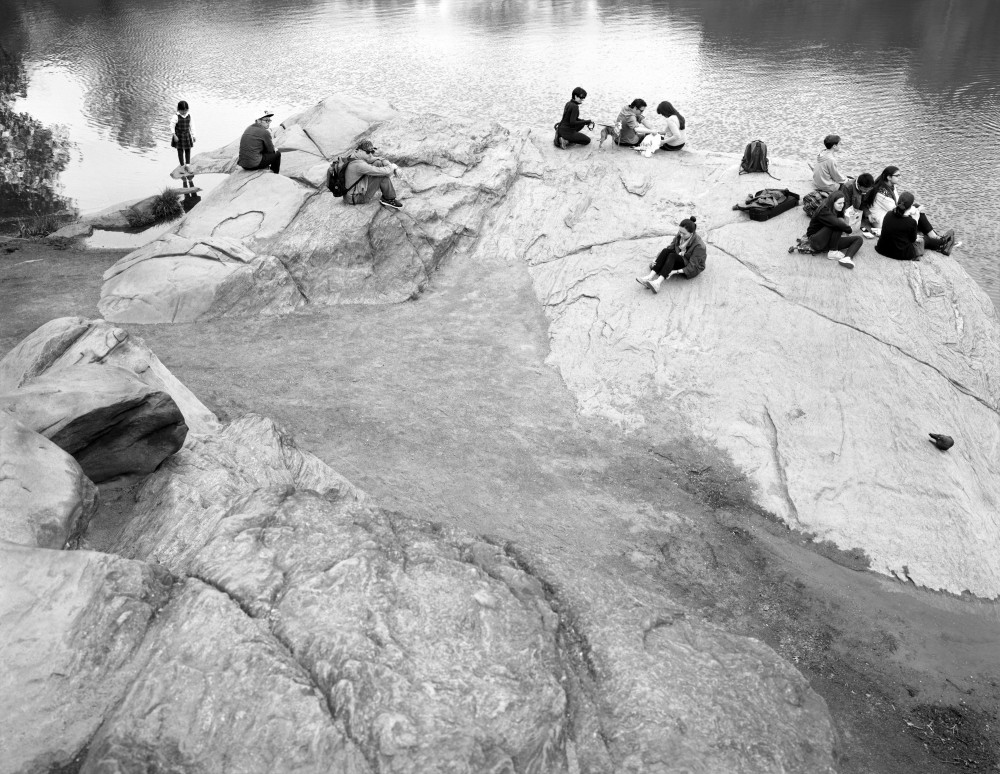

On the fourth and last day of the fair, Mitch Epstein speaks on slow photography. He shoots on film and, like Salgado, prefers to take his time. He talks us through his career - the American Power series, the Katrina pictures, his recent tree series. For these he photographs trees bare of leaves, focusing on the shapes the branches make, drawing them out of the New York landscape. One is the oldest tree in the city, in Washington Square. He draws our attention to things that are always around us yet we never bother to look at - extraordinary rocks in Central Park, brooding clouds above Fifth Avenue. His pictures are in the Whitney and in Photo London in the Thomas Zander Gallery.

© Anthony Hernandez, Discarded #9, Courtesy Galerie Thomas Zander, Cologne.

© Anthony Hernandez, Discarded #9, Courtesy Galerie Thomas Zander, Cologne.

© Black River Productions, Ltd. Mitch Epstein, The Hernshead, Courtesy Galerie Thomas Zander, Köln.

© Black River Productions, Ltd. Mitch Epstein, The Hernshead, Courtesy Galerie Thomas Zander, Köln.

The grand finale of Photo London is a talk by the great Stephen Shore with Frieze Magazine co-editor Jennifer Higgie and it’s a sell out. People line the walls and sit on the stairs. After all this talk of slow photography, of photography needing time, Shore and Higgie take the opposite tack. Their subject is Instagram. Shore is captivated by it. He relates the mobile phone to early instant cameras like the Mickey Mouse-faced Mickey Matic that he used in the seventies, the Polaroid, the Kodak SX70, and rejoices in the different flavour of the pictures one takes with these unthreatening, unassuming cameras. He compares two images of a couple of ping pong bats tossed onto the table, one taken carelessly with a Polaroid camera, the other carefully set up and shot with a Hasselblad. The Polaroid version, he thinks, is lighter, more immediate, without mediation. “The playfulness of the medium produces mysteriously evocative images,” he says. “It inspires a different way of using.”

Jennifer Higgie uses Instagram to post images of forgotten women artists. The two focus on the incredible democratization of photography that Instagram brings, allowing people all over the world to share their images and their everyday lives.

It’s a fine note on which to bring Photo London to an end. It’s been an unqualified success. Next year, the director promises, there will be another. I can’t wait!

by Lesley Downer