Andrea Blanch: In college you earned a BFA then switched to forensic photography. Did you see it as a big change becoming involved in forensic photography? Angela Strassheim: During my Junior year of college I wanted to continue to do photography as a job and was interested in Medical and Forensic Photography because deep down I wanted to be “Quincy” since I was nine years old. There wasn’t much support in my family, being a girl and wanting a real career, so I was only given community college as my option for continuing education. I was also not a very good student as my grades were low in everything besides science and art. I never received my two-year Liberal Arts degree and convinced my father to put me into a local private art school in Minneapolis. Since I eventually graduated at the late age of 25, I was very concerned about a job other than being a waitress. Forensics was another interest of mine as I contemplated starting all over and going to med school. I found a Preceptorship program in Miami that seemed perfect for gaining the skills I needed to pursue a career merging my photography interests with science of the body.

Could you explain the preceptorship program to our readers?

It’s a program where in exchange for a portfolio I worked 50 plus hours a week learning and acquiring all the skills for a vast number of forensic photography applications. Forensic photography simply means “photography of the law”. Still to this day it was my favorite job even though there was no pay. I was flying around in Blackhawk helicopters and doing surveillance from an SUV, photographing search and rescue, sometimes seizure. I would go out with the SWAT team caravan doing photographs of the entry and exit images for home invasions, going to the airport and seaport for money laundering and drug running. I also went to a number of crime scenes. Then I would follow the crime scene into the autopsy room and I would photograph the autopsies. Every day I got to learn about the inside of the body—what we look like, what disease looks like, what physical trauma looks like—and that’s what I found most fascinating. I wanted to be those medical examiners so badly; to be examining and figuring out people’s cause of death, like Quincy, a genius like him. But I have to say in the end, having a camera is where I belong. The examiners had to put their hands in these cold or sometimes still warm bodies every day and it’s a very physical job, plus all the paperwork. To photograph, it also was physical, but having one layer of distance and to see things up close in the viewfinder was what I enjoyed the most. Often times, I had to do all the cleaning of the bodies before photographs were taken. That’s a gross, messy, stinky job.

Evidence No. 5

Why was it your job to clean the bodies?

They have techs to do the cleaning but there were days there’d be 13 to 17 bodies and you want to keep things moving especially since everyone is waiting on overall photographs to be taken before they can begin the autopsies. The potential of all these photographs is that they’re used in court, so they need to be well exposed and the bodies look as clean as possible. This is really where I learned about composing an image instead of taking a picture -what you include and exclude, and considering everything in your image and looking at the space around a subject.

And you decided to take an artistic approach to things?

Well to me I feel like these images are really special and beautiful to look at, they are a rare look into how the body handles many approaches to life and death. They hold so much information and the fact that they are full color isn’t something most people get to experience. Usually when studying the human body preserved cadavers are used and the preservation solution causes everything to turn brown. I decided to continue photographing organs after my time in the Preceptorship. Years later during graduate school at Yale I was asked about my forensic photography experience and if I’d ever do a series of images inspired by it. After a lot of playing around and much thought I decided to do the series Evidence. That’s why Evidence sticks to me. I tell people you use forensic material that makes everything glow and there’s blood all over and they’re appalled. But I say ‘no they’re absolutely gorgeous pictures!’ When I was at Yale I attempted to make images of an old cleaned up death scene where someone had made many attempts at suicide over the course of a night and by early morning threw himself out of the Duncan Hotel window across from the Yale Art School. I used this luminal based mix and a fine mist in the dark of this hotel room and photographed the blue glow of the DNA all around me. The exposures were very long. It was the most terrifying experience, and I was glad to have a friendwith me. I was using 35 mm, 3200 speed color film so the images looked awful, so grainy and gray except for the blue goo that glowed all around us, on the walls and furniture. I knew this would some day be a project but I needed to figure out a better way to photograph it, to get better results, so that viewers could enter into this world.

Evidence No. 12

How did you resolve the issues to get good prints and when did you end up doing the Evidence project?

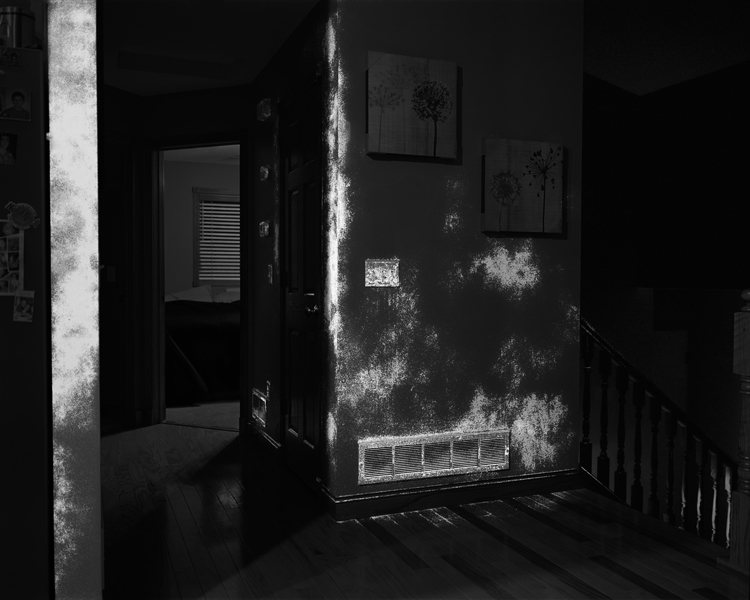

Making B&W images were the answer. When the lights are off the rooms are virtually absent of color and the blue glow of the Blue Star solution becomes the light in the room. I like how what once was a blood-stained room, now months to years later, became the light in the room guiding my way. I feel like I got lucky with the first test photos because I went through a period of images after that not working out at all. I spoke several times to Calvin Jackson, at BlueStar and he was very helpful. About a third of the way through, I switched to color film because it was easier to do the post-production and see the patterns because it was contained in a single color channel. I was able to use 800-speed color medium format film instead of 400-speed B&W 4x5 film, which cut down on the time and gave me much more tonal range.I was inspired to begin the project when a graduate student, where I was teaching in Minneapolis, was murdered by her husband in an apartment that I knew quite well years before. I had friends living there about 12 years earlier when I was an undergrad student there. I had a history myself, in that apartment, and I became obsessed with this particular case because of that, but also because it was a familial homicide which is one of my biggest fears; not totally knowing who you live with, being caught off guard fighting for my life. I got access to the apartment a year and half later and I made test images with BlueStar. The results were amazing. After that I started researching murder cases that fascinated me from memory and inspired me from online searches. I took a road trip with my then new boyfriend and tried to approach people living in these homes and apartments, but too many were unattainable, especially in such a short time frame that I had to work within. Then I decided to go to LA for several months since there were many well known cases of familial homicide there and also easy to knock on someone’s door. I also traced back years of such homicides on the Femicide reports that come out yearly in Minnesota. There were some interesting cases in Boston so I went there also for similar reasons. New York City was impossible because in almost every case I was dealing with huge buildings, long hallways, and doormen. It’s an uncomfortable situation all around.

How did you go about making the photographs exactly?

I took an exposure before the sunset so there was still ambient light present in the room and then I closed the lens and reopened it after it was dark after the room was sprayed with BlueStar. I would take usually two people with me. I’d set up two or three cameras and I would kind of know where to find something based on all of the research I did. But you don’t know until you spray. I was using a training formula of this chemical mix so that it wouldn’t be toxic to the people living in the homes. By using this it actually destroys the DNA. I liked that I was kind of releasing them at the same time. Basically I was capturing whatever DNA trail was still there.

What other types of research did you do to prepare for the shoots?

I started with Internet searches of familiar homicides. Many times I went to the courthouse if there were arrest records. I talked to neighbors. I did all of this research before ever knocking on someone’s door. And I made sure whose ever door I was knocking on already knew what had happened in their home.

Evidence No. 3, 2009

So these were people that bought the home subsequently after the murder? Didn’t they paint over it?

Yes, of course. I specific kind of cleanup crew, called a biohazard cleaning crew, is hired to remove all traces of biohazard material, basically blood, from the premises. Usually wood floors would be replaced but walls are just cleaned. They’re power cleaned, bleached, everything. The DNA is still present years later. The BlueStar crew has done tests in homes from brutal happenings from the Civil War and the DNA was still attainable. It can be a bit tricky to photograph because this substance reacts to bleach as well, but with a different glow than the bloodstain that was left. So you’ll see many times the glow present, which I would wait to subside and then the actual blood DNA lasts much longer. I start the second exposure after that bleach glow comes down so you just see the DNA. In some of the images you can see both.

So you focus on familial murders. Were any of the people you visited in the homes involved with the families of the victims?

Only one which was a rare case. It is a story of a mother while out on her daily morning walk all of her children were murdered by her ex-husband. She still lives in that house and she’s remarried and she has two more children. She’s kind of amazing. I’m like ‘How could she still live in this house?’ We had an email relationship for a while; it took quite a few months before she agreed for me to come visit her. I spent three days there. I understood why she stayed there after speaking with her. I understood her. I mean, she moved into this house while she was pregnant with her first child, that child was 18 when she was murdered. Her daughter really had a future and it was taken away. So that room is preserved. My boyfriend at the time, who is now my husband, came with me and actually helped me in photographing her room. I ended up having him write something for the evidence portfolio. It is a really beautiful piece of writing. It was tough to find a perfect piece as I had asked several others to write as well. He was able to capture in his writing first hand the experience of being in one of these rooms and sharing feelings we were both having about the situation. The first image you see in the portfolio is from that story.

You said that now feels like the right time to publish a book of Evidence. How big will the book be?

I feel like it needs to be broken up into two books. One neat and tidy of the Evidence project and another that is more like a sketchbook style with all the background texts and images from years of forensic work. There are 31 images in the portfolio and only a few texts to include. There are more of the organs that I’d want to add to the actual ‘Evidence’ book—the ones that are dealing with physical trauma due to murder and some car accidents as well.

Evidence No. 6

How is the heart series different from the organ series?

All the organs are what they are, they’re not altered, they are real. For the heart series, there are only five and they are shown together as a family portrait or sorts. There are only five because I chose only these five. They all died within 48 hours of each other. They represent family in an abstract way. Each one focuses on a different age group and death somewhat related to each phase of life. One is a child’s healthy heart, one is a teenager from a drug overdose, another mid-life gun-shot-wound, a fatty unhealthy heart from an older person, and a cancerous elderly heart. So to me, they represent family even though they aren’t an actual family. I chose the heart because it’s always recognizable and even though it’s always recognizable, seeing five of them together you see how different the heart looks from one person to another. How they’re still just as unique as a person’s face. And we can all relate to that. It’s like the connection of the head and the heart and the body.

What would you do for the second book?

I would like to do a second book that’s a more of a sketchbook style. I’ve got pieces of writings that I’ve done, newspaper clippings and many things that I’ve collected over the years. I think that would make it interesting. Letting ‘Evidence’ be its own formal, beautiful, simple book and the second more messy and playful, that is what makes the most sense to me.

What are some other ways you showcase your work?

I am represented by Andrea Meislin Gallery in NY. I had my first solo show with her this past fall. In that show I tied Evidence into my previous works demonstrating the domestic thread that runs though all of my work. I think it was pretty successful. This fall I am doing a unique show at MOCA in Jacksonville, Florida. It is an atrium space with a 20’ wide by 40’ high wall. It is seen on three different levels. It is going to be a challenging but fun show to curate as it will hang salon style and be seen from far away compared to the traditional gallery show in which you can walk right up close to inspect. The show will begin at 5-6’ above ground. I will again be mixing older work with Evidence; talking about story telling and the body investigation in fragments. I put so much into this portfolio that weighs about 150 pounds. It’s wood, 20 x 24” and lined with old felted wallpaper that kind of mimics the home. All 31 pictures and two texts are in there along with one case file that’s explicit in all the details of one of the crimes. I chose the case that I felt tied all of them together; it has aspects of each case in it.

In your opinion in what you’ve seen, where is the temptation in killing someone?

I don’t see murder as a temptation at all; especially in my experience of doing the evidence series and all the people I spoke to. They’re crimes of passion. Most of these people started out by loving each other, they committed to one another, and they were in some type of love relationship. A lot of these murders happened over preparations for dinner. Conversation goes wrong and people snap and grab a steak knife. That was always my biggest fear, not knowing who you’re living with. They’re the partner you’ve chosen. What does it take for somebody to snap? What triggers that thing that happens in somebody’s brain? How do you trust somebody? How do I know you? How do you know me? It’s scary. It’s also what my husband’s writing is about in the portfolio, we were sort of questioning the other as we stood in this girls bedroom waiting together in mostly silence and amazement at the tragedy we saw before us.

Evidence No. 1, 2009