Image above: Edward Lachman on the set of I'm not There, 2007

ANDREA BLANCH: Can you speak about your art and the connection between photography and film?

ED LACHMAN: I came out of art school, so I think of imagery on a conceptual level as well as how you use images to tell stories. Images for me are like painting, whereas films have a beginning, middle and end to tell a certain thematic narrative. When images work, they’re open-ended. They allow the viewer to complete the story. I respond to the idea that people can subjectively imbue an image with their point of view. In film, you can show where you are, but it’s much harder to enter the interior world of a character. What I try to do in film is to create a world that allows the viewer to discover who this character is through images. In writing, it’s just the opposite. You can enter the interior world of the character but it’s much harder to show where that character is.

AB: You’ve said that taking photographs on set is part of your filming process, like note-taking. When did you realize these photos had artistic value in themselves?

EL: When I was doing “I’m Not There,” a large part of the film was in black-and-white. I used a black- and-white polaroid camera for exposure checks, purely for utilitarian reasons. Because the film was shot in black-and-white I had the only reference in how the wardrobe, the set, the makeup, the way the actors would look in black-and-white. Cate Blanchett saw some of these photos and asked me if she could have one. I have taken thousands of these photos over the years as references and I never did anything with them. I put them in a box someplace. It made me think about these as private moments with the actors. I realized I had captured personal moments for the actor—being in character, or within themselves. I scanned some of these polaroids and made larger prints and did a show with them. That was the origin of the series I called “Exposure Checks.”

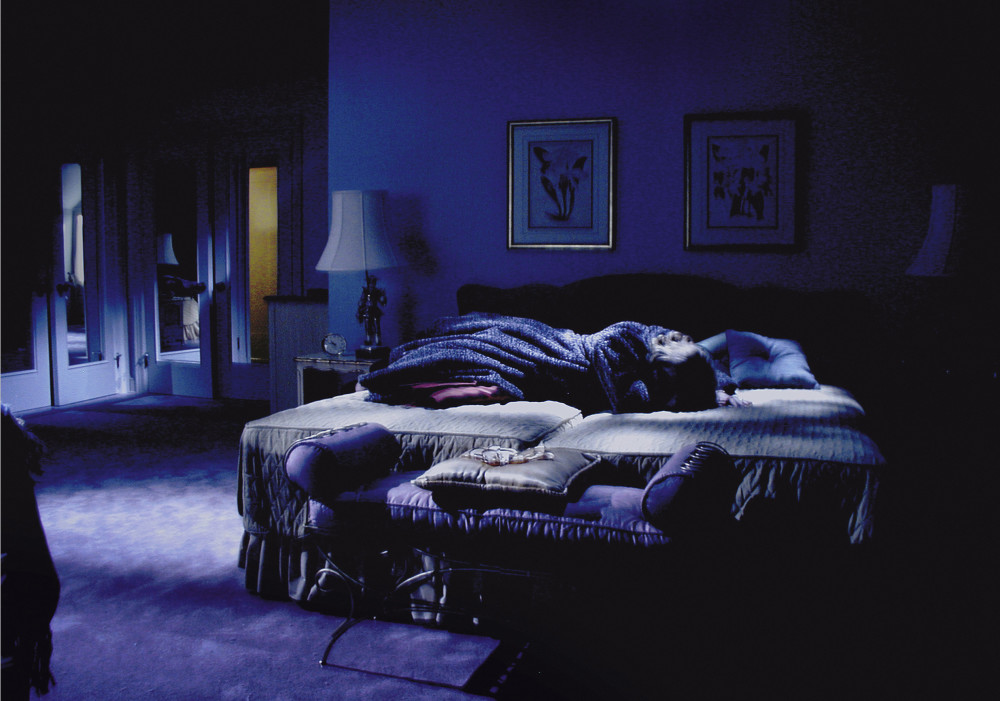

©Edward Lachman (Far from Heaven, 2002)

©Edward Lachman (Far from Heaven, 2002)

AB: You’ve described your photographs as “open-ended images.” What do you mean by this term?

EL: Images work for me when there is an open narrative. The beauty of a photograph is that it’s a non- verbal form of communication like music. It can reach people intellectually or emotionally. I love the idea that you could create a narrative in reality that is left for the viewer to complete. Images are the subtext for the psychological world you’re creating for the characters. For me, photography is about documenting your personal experience. What you’re looking at is a subjective point of view. For me, in a Robert Frank photograph, I’m experiencing his personal experience in a poetic realism. The word ‘eidetic’ encapsulates what I think photography is. It is about constituting the visual imagery vividly through what’s reproducible of your own self.

AB: What about conceptual photos?

EL: That’s a different world. I respect it and sometimes like it but it usually doesn’t speak to me.

AB: Some of the photographs in your shows are still frames from your films. How do you think an image is changed when it is isolated in this way?

EL: It goes back to what I’m saying. I’m not a still photographer on a set. I’m a motion picture camera guy. If you take a frame out of a film, which I’ve done in an exhibit at the French Cultural Institute, it opens up the possibility of what the narrative is, because the image is isolated out of the context. If you extract an image out a film, you can allow the audience to create their own narrative as to what that image represents, like a painting. I’m always trying to find what is unique in the story that allows you to approach the story in a visual way. In other words, no story should be told the same. You have to look for clues. All those things are subtext to the story.

©Edward Lachman (Far from Heaven, 2002)

©Edward Lachman (Far from Heaven, 2002)

AB: So “Shadow”—an installation that you did at The Whitney—came out of an unfinished film that starred River Phoenix.

EL: Slater Bradley, an artist, came to me and he had done a number of projects about dead icons that were important to him as he was growing up. I was resistant at first to do anything about River be- cause there was so much publicity around him. I looked at Slater’s work and it was very connected to what his other work was. We were originally going to recreate the last scene that I shot with River, where he was in LA. We had built a paper mache tunnel and he has a long soliloquy with Judy Da- vis. It was apocalyptic what he was talking about, because he died that night. The other aspect was the last take: the camera was never turned off. You heard the director say, “Cut” and the lights went down, but when the assistant turned the camera off, I inadvertently turned the camera back on. You saw River become a ghost. He was in a silhouette against candles lit in this cave. He stood there for about ten seconds. Then he walked up to camera and his body covered the lens. And it went black. That was the image we were going to recreate. It was too expensive to recreate the whole set, so I said to Slater, “Why don’t we go back to the area in Utah where we shot the film?” It was this incred- ible area within a national park. I actually bought a ranch nearby. I said we could go to the location where we shot 17 years ago and see if we could find anything that was left. Well, we found the most incredible things. We found photos in the bar that belonged to River’s friends. We recreated another narrative with a doppelgänger. I became a doppelgänger myself by photographing a location that I had already shot on with the idea of River’s ghost.

AB: Unlike photography, cinematography is collaborative. It’s not just a personal vision. You have to work with a team. What is the process like for an artist? Can it be frustrating?

EL: I always say the relationship the cinematographer has with the director is like a marriage. Sometimes when you disagree with the director and you both have strong opinions about the visual interpretation of the story, you have to find a compromise, and that becomes better than what either of you had first con- ceived. Not all directors are visual. I like to work with directors that have a strong visual sense, like Todd Haynes, that you can plug in to their vision. In Europe, I find the language of how you tell the story is as important as the story you’re telling. In the studio system you’re expected to shoot the film a certain way so that you can control the images in the editing process. Whereas in independent or European cinema, images are more about a point of view of how you tell a story. Many scripts I read from Europe are not dialogue- based. They’re written through description and ideas about what the images will portray. Scripts in Amer- ica are only written through dialogue. I always found that a limitation to understanding how to tell stories.

AB: I find that very interesting because it explains why I always find European films more natural.

EL: They come from a visual tradition through painting. In America, up until the abstract expression- ists, we didn’t create our own visual idiom that was uniquely American. We come out of a more literary tradition. That’s why I think America doesn’t deal very well with different forms of irony. For people here, it has to be upfront, reinforced, black-and-white. They don’t deal well with the grey area.

©Edward Lachman (Far from Heaven, 2002)

©Edward Lachman (Far from Heaven, 2002)

AB: It’s difficult to pinpoint a consistent style in your work. Your process is chameleon-like in a way because with each film your style changes. You often mimic other filmmakers as in “Far from Heaven” and “I’m not There.” Why do you prefer to work in this way?

EL: Todd Haynes comes from a world of semiology. He uses film language as a metaphor for his story- telling. It isn’t just to make the film look like a Douglas Sirk ‘50s film, but it was about using melodra- mas—heightened gestures and mannered stylization—to express the characters’ claustrophobic stories of disillusionment in their picture-perfect world, that they’re seduced by, but can’t act on their own personal needs. Sirk was using the surface beauty of things as a form of repression. He was showing something about the false sense of optimism in America, about what the values of our lives were. That’s the way Haynes was playing with melodrama. Would it work today the same way it worked in the 50’s? The dramatic irony, through music, color, lighting, and camera movement, becomes a descrip- tion of a world that ideally could be but is never allowed.

AB: How do you go about planning a film visually and how is that process different from photography?

EL: I’m interested in photography as an immediate response to something that I see. I’m interested in street photography. I’m not interested in staged or constructed photography. I think someone who does stage photography can have a particular narrative, but I don’t get the form over content photography.

©Edward Lachman (Ken Park, 2002)

©Edward Lachman (Ken Park, 2002)

AB: Movies take a long time to complete, while photographs do not take as long. Do you prefer one over the other?

EL: No, it’s about the process. Even in film, I prepare to capture what’s spontaneous about the image. To me, all films are some kind of documentation. Even in the narrative film, no take is ever the same. The actor doesn’t stand in the same light, the way the camera moves is never the same. For me, all images or all forms are a documentation, and that’s what I love about still photography: It becomes a documentation of your experience in that moment.

AB: You’ve talked about how color is not just decorative but can be psychological. Can you give me an example from your work where you try to use color to bring out a psychological dimension?

EL: When I studied painting, I looked at how color can represent a psychological emotion. I like to play with a two-color palette where there is a receding and an advancing color. Warm colors are advancing and cool colors are receding. In “Far from Heaven,” I showed night change as their relationship was disinte- grating. In the beginning, the night has more of a periwinkle and purple tone. As the relationship changes, it became more acerbic and more yellow green. The relationship between Kathy and the gardener was saturated with natural colors, but they were primary colors. Then I showed the aberration of the husband in the gay bar in magentas, yellow-greens, and colors that would be secondary. In “Carol,” my latest film, an adaptation of a Patricia Highsmith book that takes place in the early ‘ 50s, I used a muted palate of colors, more in magenta and greens. I tried to reference the way film stocks responded to colors in the ‘40s and ‘50s and their grain structure. We shot in super 16, not in 35mm film, because film stocks have become almost grainless. In the digital world, filmmakers try to capture the texture and exposure of film grain, but because the image is pixel fixated on one digital film plane, it loses the depth of film’s three color layers, and the way grain interacts with exposure, which also affects how colors interplay between each other.

©Edward Lachman (Ken Park, 2002)

©Edward Lachman (Ken Park, 2002)

AB: What is it about Todd Haynes that you like to work with?

EL: Todd Haynes, Paul Schrader, Todd Solondz, and Ulrich Seidl. They’re able to understand cinema and the language of cinema, but they’re also telling their own stories. The incredible thing about great directors is that they’re original in the stories they want to tell. They have a personal connection to the stories they’re telling. Someone like Haynes has such a control of understanding the language and im- ages. He doesn’t reference images as an imitation. He references images as a metaphor for the story. To me, images work best in metaphor. Images aren’t about representation. They’re about an interpretation of the world you’re portraying. I’m interested in the form of poetic realism. It is a subjective viewpoint and moral position that tells the poetic or psychological truth of an image.